|

|

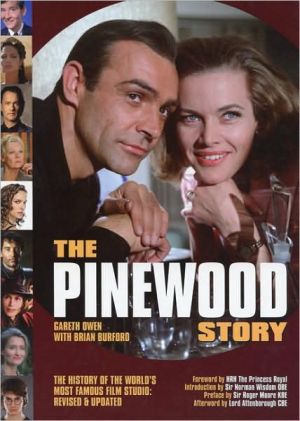

The average rating for The Pinewood Story based on 2 reviews is 3 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2013-11-09 00:00:00 Chris Shallicker Chris ShallickerThis book is a classic example of form follows function, or perhaps, form follows content. It's a bewildering and meandering book, about a bewildering and meandering subject: Soviet economic policy during Stalin's rise to power. Yet, through a detailed analysis of the Soviet economy, with a particular focus on the all-important metals industries, Shearer is able to show just how contested the nature of that economy was even after Stalin had taken over from Trotsky and Bukharin. I had heard all about the anti-expert campaigns in Mao's China in the 1960s, where the Red Guard was extolled to attack any semblance of education or intelligence in leadership, but I had never heard of the spetseedstvo, or specialist-baiting campaigns, of 1928 to 1930 in Soviet Russia, where mining engineers and other supposed "wreckers" were taken to task and eventually replaced by self-righteous communist youth for insufficient ideological fervor, devastating much of soviet industry. It's almost a perfect parallel to China's horrific experience, yet little remembered today. At the same time the government's efficiency inspectorate Rabkrin, the equivalent of America's GAO, led by the intense Georgian Sergo Ordzhonikidze and a host of ex-Trotksites, tried to take some of this fervor and turn the whole economy into a permanent military campaign, for instance by celebrating the accomplishments of shock worker brigades to upset the recently installed Soviet managers. Rabkrin's constant, carping "reports" on putative inefficiencies in different sectors or firms became the equivalent of emergency orders that upset whatever temporary plans local groups had settled on. Yet Shearer shows that another force also grew more prominent in these years, the syndicates. While originally different state firms had tried to find other state "purchasers" for their products, gradually trade associations called syndicates formed to organize sales. Soon the servant became the master and the syndicates, with acquired credits from Gosbank, started to control production in order to control selling, and quickly grew to become the most powerful organizations in the economy, breaking down the previous groups of hierarchical trusts, glaviks (or sector-specific production organizations, like Glavmetal), and the economic planner Vesenkha, which had all hitherto tried to rationalize the economy on German lines. The overtly market-based systems of syndicates, however, eventually caused them to become subject to and fall before the ideological campaigns. As the wealth of Russian names above makes clear, this story can quickly get confusing. But the reason this book is of more than antiquarian interest is that it is a stellar example of bureaucratic in-fighting when the stakes are unbelievably high, namely, control of the one of the world's largest economies. It also shows how an attempt to control an economy from on high eventually degenerated into petty fiefdoms, where firms were forced to control all their inputs because they couldn't trust the other firms to provide them, and where the intense control of workers by unaccountable foremen, once denounced by Bolsheviks as the height of tyranny, became the norm once again and piece-rates proliferated. Attempts to centralize all credits in the Gosbank backfired and lead to rampant waivers and inflation. Attempts to cut bureaucracy through functional silos backfired and lead to a growth in bureaucracy. Everything they Soviets tried seemed to achieve its opposite, and this books explains how it all operated for individuals on the ground who had to deal with this nonsense. |

Review # 2 was written on 2018-08-13 00:00:00 Diana Gail Noble Diana Gail NobleWho was really responsible for Hitler and World War II? In 1965, just twenty years after the collapse of the Nazi regime, I visited Auschwitz. Even though that was nearly half a century ago, my memory of that shattering experience remains vivid: the mountains of human hair, eyeglasses, and gold dental fillings; the photographs of skeletal prisoners staring glassy-eyed from bunk beds crowded together in darkness; the route from the trains to the barracks to the ovens followed by more than one million European Jews from 1941 to 1944. Those disturbing images kept coming back to me as I made my way through the pages of Hell's Cartel, Diarmuid Jeffreys' compelling story of the role of Germany's largest industrial concern in the rise of the Nazis and the conduct of World War II. Few readers under the age of 60 are familiar with the name IG Farben, but for most of the 1920s and 1930s, the company ranked fourth in the world, just behind General Motors, U. S. Steel, and Standard Oil of New Jersey. However, IG Farben was more than another enormous business ' it was, in fact, a cartel, or association of separate huge firms for much of its existence ' and, more than any other company, it personified German science and Germany's rise while it dominated much of the German economy between the two World Wars. (The name IG Farben is an abbreviation for a string of German terms meaning "community of interest of dye-making corporations.") Hell's Cartel opens in Nuremberg in 1947, where 23 of the highest-ranking Nazi political and military leaders of the Third Reich had been tried, and most found guilty, in a lengthy war crimes trial that ended the preceding year. Now, in one of a series of subsequent military tribunals, 24 of the directors of IG Farben were going on trial, too. With the scene set against the devastation of urban Germany, Jeffreys then launches into the history of IG Farben, beginning in the 1880s with the first attempts in Germany to challenge English control of the chemical dye industry; the emergence of several large companies famous in their own right (Bayer, BASF, Hoechst, Agfa) as the German industry overtook its competitors and leapt to the lead in dyestuffs, pharmaceuticals, and chemicals; and the two-decade quest of Carl Duisberg ("the world's greatest industrialist") to convince the leaders of competing firms to combine with his own company, Bayer, in an all-German chemical cartel. When Duisberg finally won the day in 1925 and the IG Farben was born, the foundation was laid for one of the darkest chapters in the history of business. In Jeffreys' view, the fatal moment came in 1933, shortly after Hitler came to power, when the IG's chief executive, Carl Bosch, entered into a huge government contract to produce high-octane synthetic fuel for Hermann Goering's illegal air force. "The agreement Bosch had signed," Jeffreys writes, "was far more than the fulfillment of his long-held ambitions [to commercialize synthetic fuel]. It was also a pivotal moment in a sequence of events that would lead inexorably to the blitzkrieg, to Stalingrad, and to the gas chambers of Auschwitz." Although the IG manufactured thousands of products through its extensive web of companies and subsidiaries ' ultimately, throughout the lands Hitler annexed from 1936 to 1943 ' its military significance lay chiefly in its production of synthetic fuel, synthetic rubber, and explosives. However, for many observers, the cartel's most notable product was the Zyklon-B gas used to exterminate millions of Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, and others judged undesirable and unfit in the deranged mind of Adolf Hitler and those who followed his lead. Jeffreys' judgment about the preeminent role of IG Farben is unequivocal. "Had the IG's managers found the courage to oppose doing business with the Nazis in the late 1930s, or had they been even marginally less compliant, Hitler would have struggled to get his war machine moving." Going even further, the author quotes one of the company's top executives, Georg von Schnitzler, who concluded after the war had ended that the firm gave "'decisive aid for Hitler's foreign policy which led to war and the ruination of Germany . . . I must conclude that IG is largely responsible for the policies of Hitler.'" It is difficult to imagine a more dramatic example than IG Farben of business unmoored from any moral purpose ' not just supplying the products that literally fueled the Nazi war machine and sponsoring the gruesome research of Dr. Josef Mengele (the notorious "Angel of Death"), but going so far as to build its own concentration camp for Jewish slave laborers at Auschwitz. [Note: "Auschwitz" connoted a network of more than forty camp facilities, including the Birkenau extermination camp and the IG's installation near the synthetic rubber plant it was building near the Polish border town of Auschwitz.] In the final pages of Hell's Cartel, Jeffreys returns to the 1947 IG Farben trial in Nuremberg, detailing the testimony and attitudes of the two dozen defendants, introducing the American lawyers and judges, and relating the court's verdict on each of the defendants. I won't summarize here the outcome of the trial. Suffice it to say that the final chapters of this book make the whole story well worth reading. Diarmuid Jeffreys is a British journalist and television documentary producer. In an earlier book, Aspirin: The Remarkable Story of a Wonder Drug, he researched some of the early history of Bayer and other German pharmaceutical companies that figure in central roles in Hell's Cartel. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!