|

|

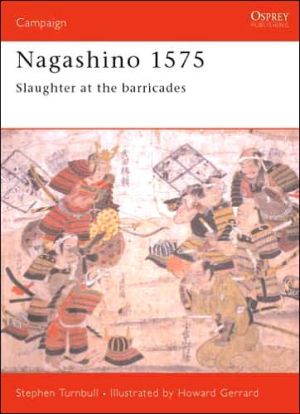

The average rating for Campaign #69: Nagashino 1575 based on 2 reviews is 5 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2017-01-05 00:00:00 Lissette Luster Lissette LusterTuyệt hay. 5 sao luôn. Cuốn này dạy cho mình rằng trận Nagashino không phải giống như Kagemusha và hỏa mai của Oda không phải là gattling gun bắn chết Takeda như bắn Tom Cruise. |

Review # 2 was written on 2009-04-12 00:00:00 Francesco Paolino Francesco Paolinopick up any standard history book on Japanese history from a western point of view and most will tell you the same story; Japan under the Tokugawa rule isolated themselves from the rest of the world and despises trade with outsiders until 1853 when the US forced Japan to open itself to the world. It is a neat story and still remains the prime example of literal gunboat diplomacy, yet this book by Brett L Walker tries to justify this erroneous view of a hermetically closed Japan by looking way up north to the islands of Hokkaido, Sakhalin and the Kurils. These islands were the last homes of a group of people whom by the medieval period were known as the Ainu. A people who were less stratified then their Japanese neighbors, with whom they once shared the main islands of Japan, dedicated to a life of small scale farming, fishing, whaling an ritualized hunting with clear shamanistic tones. These smallish communities interacted with their surrounding world, Ainu on Sakhalin were part of the Chinese tributary system, Ainu of the Kuril traded with various east Siberia communities (and later on Russian traders) while those of Hokkaido were slowly but surly integrated in a Japanese hegemony. As the title states, this is a book about expansion, although the title says 1590, the book does briefly go over the period before up until the major pieces are set on the board. The Ainu who went from an occasional trade with Japan and ceremonial visit to regular contact, the establishment of a new centralizing Japanese state, the Edo regime and the granting of those regular trade contacts by this new regime to the Feudal Matsumae family. Throughout the book Walker makes several comparisons between the interactions and changing relationship between the Japanese and Ainu, and the changing relationship between English settlers and native Americans in the same period. This serves two purposes, one is to emphasize that Japan was not as dissimilar in its contact with non Japanese people it deemed barbaric as the English state was with those peoples it deemed barbaric. The second purpose of this comparison, is to show how these kind of unequal interactions can have a similar effect on those weaker in the interaction despite the huge contextual differences. This impact, according to Walker, profoundly changed and shaped the Ainu communities. What started out as an occasional trade between (perhaps not equal) free peoples; who could choose to trade on terms both deemed acceptable, quickly and increasingly so became a vector for dependency on the side of the Ainu for Japanese goods. Dependency also to a lesser extent for the Matsumae who needed Ainu trade goods to participate in the Tokugawa political system. This story is indeed quite similar to what happened to various North west American natives, as foreign manufactured goods started out as curiousa to be traded for some animal hides but quickly became status symbols as they grew in number, pitting communities against each other to acquire the necessary trade goods until finally communities had changed profoundly to meet the needs of the traders. So it went with the Ainu, Saké (as was rum for native Americans) became a staple for the Ainu, replacing traditional light alcoholic brews, drink alongside tobacco, iron utensils, swords and other objects. Even rice increasingly became a vital good to be traded for by the Ainu, as more and more people went out to spent time hunting for animal-pelts, fished Salmon to be smoked and exported or trap live hunting hawks to be traded. This proces fairly quickly made whole communities depended on trade to survive. It forced them to become laborers for hire to pay of credit and debt or allowing Japanese small scale gold miners and lumberjacks to devastate traditional hunting lands after they had been picked clean of game. This story of growing dependence was, as it was in north America, not a linear story. Ainu tried to to resist both with violence, war and maintaining some adapted new forms of older subsistence and they tried to keep other trade contacts outside Japanese control. Some even tried farming rice as to lower dependency on these proto capitalist traders who where fully aware and acted upon the inequality in power to squeeze out the most of these communities. These traders also made sure it stayed that way and who did not hesitate to make the exchange even less advantageous for the Ainu when they could. Licensed as they were by the Matsumae to extract these goods (whose original mandate had included treating the Ainy fairly) and who backed them up with force and threat of violence if the traders were threatened by disgruntled Ainu and who themselves could always count on Edo support if resistance became to united and strong (as it did briefly late 17th century) for this out of the way feudal family. As the title says, this is a book on ecology and it is not limited to impact of hunting and fishing or lumber and mining on the landscape, the book goes in detail on the impact of smallpox and syphilis on the Ainu and how it weakened communities forcing them in their growing weakness to rely even more so on the goodwill of the traders who were the source of their misfortune. Walker does also include several proofs of how the Shogunate did at various times tried to help Ainu populations in mitigating the effects of small pox and a vaccination campaign in the 19th century, so this is no case of deliberate actions that smallpox spread. Syphilis however.... Walker does not make the comparison, but I will; the way it was spread in the Ainu communities reminds me on similar diseases spread in native communities in the amazon rain forest. Native men contract the diseases via prostitutes where they go and trade to acquire manufactured goods, they spread it among young women in their communities or they got infected via rape/ debt payment by Brazilian miners, loggers, hired thugs and traders who by doing so assert their superior power over local communities. As with these natives, when Ainu complained about these rapes by Japanese, they got shushed with a few bundles of food, drink and 'gifts' while the disease lowered fertility and the health of children with infected mothers. So what was the end result of this growing dependency and what does it teach us of Japanese society of the time? To me it disproves the notion that Japan was isolated, it did interact with people beyond what was considered proper Japan, it expanded its sphere of influence to islands that are now either part of Japan (Hokkaido) or have been claimed in the past (and still claimed by nationalists) Kurils and Sakhalin, the shogunate did allow foreign trade as long as it was (in)directly under its control(it freaked out and investigated thoroughly when suspicions grew of possible sizable unlawful trade between the Russians and Matsumae through Ainu middlemen), Japanese society had (limited) room for autonomous traders who were (proto) capitalist but firmly under the feudal banner. As from an interactions point of view; the story of the Ainu, which continues until this day, is one of inequality and what it does to communities on the losing side. The winner forces the loser to dance to their tunes and shapes their counterpart to fit in their political, economical and cultural cadre. Neither does this have to directed from all the way on the top either, it was the Matsumae who allowed the traders to do most of the shaping and molding as long as their molding strengthened their position in the Shogunate political system. In fact when Shogunate officials did travel to Hokkaido, they were often very critical of the abuses and unfairness they saw, yet until the 19th century, the Matsumae kept their little monopoly. The tragedy of it all is that for so long Hokaido or Ezo as it was called then, was not deemed true Japan until the 19th century with its "barbaric primitive" inhabitants, addicted to liquor, who could not even sustain themselves and suffered such tragic diseases. At that point the Soghunate stepped in, pushed the Matsumae out of the way and introduced direct paternalistic control on the Ainu and their still resource rich land. Again Walker makes the comparison with native Americans, whose devastated communities in the mid west came under the care of the federal government who enforced the myth of a primitive society that needed to be saved from itself, ignoring the impact decades or hundreds of years of contact on these communities. One final note, this island would also become the last stronghold of the Shogunate soldiers during the Mejii restauration as the stillborn Ezo-republic. the Shogunate last refuge after Japan had changed profoundly after its aggressive contact with stronger outside partners who wanted Japan to trade and participate in their order of things. It is profoundly ironic..... |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!