|

|

The average rating for The Man Who Melted based on 2 reviews is 3.5 stars.

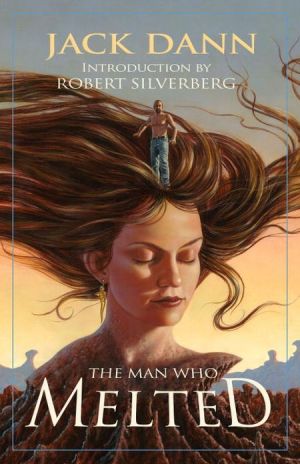

Review # 1 was written on 2009-03-25 00:00:00 Lonny Edwards Lonny Edwards(Reprinted from the Chicago Center for Literature and Photography [cclapcenter.com:]. I am the original author of this essay, as well as the owner of CCLaP; it is not being reprinted here illegally.) As I've mentioned here before, most fans of science-fiction consider the genre to have now gone through four major periods (or "ages" as the nerds call it) of history: there is the "Golden Age" from when the genre first came into being in the early 1900s; the "Silver Age" of Mid-Century Modernism, when engineers in skinny ties ran around strapping cowboys to the noses of jet-fueled rockets; the "New Age" of the countercultural '60s and '70s, when like everything else in the arts suddenly all the traditional rules of SF were up for grabs; and the "Dark Age" of the '80s and '90s, when postmodernism combined with punk-rock to produce a whole series of heady neo-noirs. (And also as I've mentioned before, I believe that we've been going through a whole new age of SF since around September 11th or so, simply that most people haven't acknowledged it yet, what I suppose you could call the "Accelerated Age" [after the Charles Stross novel:] or the "Diamond Age" [after the Neal Stephenson one:], a Web 2.0ey wave of ultra-optimistic tales concerning the coming merger between the mechanical and the biological...but that's a whole other Locus guest article for a whole other day.) But just like any artistic medium that a person tries to categorize in an overly general way, these four ages still leave a lot of SF over the years unaccounted for; there are for example all the transitional periods between these ages, the counter trends that happen within any major period of history, not to mention the works so jarringly unique that they exist outside of any traditional classification at all. Take for example the Nebula-nominated 1984 novel The Man Who Melted by Jack Dann, celebrating its 25th anniversary this year with a slick new reprint by our friends at Pyr, a product of one of these exact transitional periods of history I'm talking about; because much like his contemporaries Philip K. Dick, Tim Powers, Roger Zelazny, Larry Niven and others, this is one of the projects to bridge together the New Age and Dark Age of SF, one of those books that helps create a direct line between, say, Frank Herbert and Alan Moore, when otherwise it might be difficult to see such a connection. Or if it helps to think of it in terms of popular music, think of Dann as maybe the SF equivalent of Iggy Pop or the New York Dolls, artists who embraced many of the hippie-like elements of the old '60s counterculture while paving the way for the anger and nihilism of the '80s punk movement directly after them, who took the sexuality and intelligence of the free-love years and added a raw, meth-tinged intensity to it. It's not exactly a masterpiece like is found smack-dab in the middle of major periods of artistic history, but certainly an important and well-done book that shows you how the genre got from one polar extreme to almost its exact opposite in less than twenty years; and since I'm a particularly big fan of these overlooked transitional times in history, of course I'm going to think this book still well worth your time to this day. Set 200 years in the future, The Man Who Melted portrays an Earth with the same kind of relationship to us as perhaps our modern times would look when viewed by an early Victorian -- that is, a lot of what was there originally is still with us, but with yet another new layer of human technology slapped on top of everything, in this case resulting sometimes in entire cities that now have a glittering "grid" of new infrastructure hovering 30 or 40 feet above the old one, effectively turning all the old streets of New York and Paris (to cite two examples from the book) now into Klieg-lit subterranean crime-infested underworlds. And there's a good reason for this, too, because of a major global natural catastrophe in their past that no one could've possibly predicted: called the "Great Scream," it occurred when one day suddenly thousands of cramped-in urban dwellers around the world started forming by accident a psychic connection with each other, creating these chaotic city-sized hive minds so overwhelming that they caused psychotic snaps among all those "hooked in," resulting in crazed mass rioting that nearly destroyed the planet. And although the worst of it is now over, no one is quite sure when another outbreak will occur, which now gets all national governments around the world nervous indeed whenever too many people gather in one small place; and in the meanwhile, many of these "Screamers" who made up the destructive hive mind are still alive and roaming the streets, merely schizophrenic by themselves but becoming a killing mob whenever a critical mass gathers, which has necessitated the movement of all the non-mad city people into one urban layer higher in the sky, leaving the street-level layer below to the schizos and criminals. And so as you can imagine, this has had a profound impact on all kinds of details concerning daily life in the future; for example, the sanctity of human life itself seems to be worth less in this post-Scream society than in our times, with such activities as gambling for your own internal organs now their equivalent of a "high-stakes night out" at the casinos. Also, sexual norms have become quite different 200 years in the future; it's now considered perverted to not be bisexual, for example, and menages-a-trois are now considered another legally-binding form of cohabitation. And in the meanwhile, turns out that this Great Scream has left behind a whole new form of human consciousness that used to not exist before, kind of like if you woke up tomorrow and saw on the news that ESP had finally been scientifically proven; not only can people like lovers now psychically connect voluntarily through concentration and practice, but mechanical devices have been built that make this connection automatic, inspiring not only a whole new field of psychiatry but a whole new form of gambling (not to mention a whole new type of bordello). And so that's brought about a dualistic way of thinking of these psychic connections, as "dark" ones versus "light;" and that's inspired the creation of a whole new religion on top of everything else, people who call the Screamers "Criers" instead and believe them to be a form of angel, here to usher humanity into its next tier of evolution, and who hold elaborate illegal rituals where an entire congregation will hook up to a Screamer/Crier at the moment of their death, where acolytes are plunged into a kind of deep psychotic dive that they must mentally "journey" their way out of in order to reach "enlightenment," and thus gain the ability to communicate psychically with each other whenever they want. Yeah, not exactly Star Wars, which is why these types of books represent only a minor transitional period of the genre's history, but why fans of this period love these books with such an intense passion; because they are extra-dense, extra-subversive tales designed specifically for a smaller niche audience, stories that pile on layer after layer of stream-of-consciousness and eastern religious thought and uncomfortable sexuality. Take for example just all the circumstances surrounding our main character Raymond Mantle, living his life in the middle of all this mess: his wife was one of the many victims of this Great Scream who was turned into a wandering Screamer herself, but with Mantle no longer having any memories of her because of he himself being a minor victim of the Scream too, who is now seeking out this highly dangerous dead-Screamer psychic-joining process that this religious group base their rituals around, so that he can connect with the hive mind and try against hope to discover information about his missing spouse. Freaky enough for you yet? How about adding the fact that the only way he can do this is by entering a sexually explicit threeway relationship with the wife-lookalike who wants to be his new girlfriend, and his platonic same-sex best friend from college who he has a subliminal love/hate relationship with? Now is it freaky enough? No? Well, how about if the missing wife in question is actually Mantle's sister as well, and that the two of them have had an incestuous relationship for decades? Now is it freaky enough? There's all kinds of weird, morally murky things like this going on in The Man Who Melted; and Dann certainly does not make any of it easy to comprehend, either, writing in a convoluted, dreamlike personal style that's hard many times to keep up with, providing very few out-and-out clues about this ephemeral, purposely spotty backstory but rather making you piece it together yourself a bit at a time as you make your way through it (and in fact, to give you fair warning, I may be way off with some of my own backstory info today; I'm making an educated guess at it too, just like everyone else). But this is precisely why people end up loving books like these, for the same reason so many love Dann's more well-known peer Philip K. Dick; because these kinds of books present a legitimate challenge to the well-read intellectual, a sort of "anti-airport read" if you will, where the whole point is that you have to both be smart and pay a lot of attention to have even an idea of what's going on, but will be rewarded with untold mental riches for doing so. And the attention-paying reader is indeed rewarded by the end of this book, with the manuscript actually having a lot of thought-provoking things to say about love, about letting go, about friendship, about the special connection that seems to exist between two people in an intimate relationship, but with these insights only coming when one is really getting what Dann is going for in the first place. It has its problems, and I'm sure its detractors are highly tempted to dismiss it as a trippy mess; but even this book's lovers I bet are bound to agree that that's the entire point, that it's an unabashed trippy mess designed exactly for the types of people who like trippy messes. (Like Donnie Darko? Then you like trippy messes.) In any case, The Man Who Melted for sure deserves more attention and more historical acknowledgment than it currently receives, and I applaud Pyr for reissuing it in a major new way and with a major new PR campaign behind it. For all of those who have ever wondered how the peace-loving flower children of the '70s became the safety-pinned punks of the '80s, this book goes a long way towards explaining. |

Review # 2 was written on 2019-01-14 00:00:00 Steve Howden Steve HowdenIt's weird. Well written, starts well, then slowly goes downhill from there. I think the title refers to, this case, me as the reader. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!