|

|

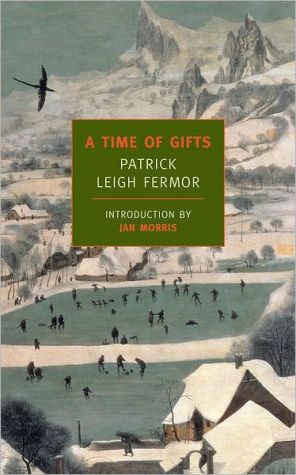

The average rating for A Time of Gifts (New York Review Books Classics Series) based on 2 reviews is 4.5 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2011-06-11 00:00:00 Dave Adams Dave AdamsI'll have whatever this guy is having. Yeah, the one making the embarrassing noises and eating ambrosia without a care in the world. This ridiculous guy right here. Fermor is kind of my hero. He represents something I've always envied. You know those people who can make a thing, an occasion out of anything, out of doing errands if they must? It's not just an Always Look on the Bright Side of Life (da da da dah dah da dah da!) thing, it's a way of not letting a surface presentation of boring be the end of it. Their minds are always working, and can always find something to think about, even at the most mediocre of tourist traps, even at the most average performance of the thousandth rendition of Pachabel's Canon they've been forced to listen to. Fermor is one of these people. I mean, he tries his best to minimize the reality of it, but he walked across the north of Europe in the depression ridden 1930s in the depths of a horrible winter, where snow covered the otherwise picturesque scenery and where Hitler was in charge. He slept in barns covered in ice, had his belongings stolen, had to go door to door peddling his sketching hobby in order to feed himself, and again, need I say it, NAZIS. This trip could have been a nightmare, or he could have sketched it as one. Who would question that in a narrative written about Europe of 1933, with the clouds closing in? But instead of touting himself as a prophet or a self-important chronicler of the troubles of the interwar years, Fermor makes himself a magician. He is the Guide, the Gandalf, the ghosts of Christmas Past, the curator, the Brothers Grimm, the wise child who knows the way through the woods. There is darkness, but it is the kind of darkness that the story needs, a supportive depth that allows us to appreciate the worth of our Guide. Fermor has two gifts that allow him to do this. One is a breathtaking capacity for rapture. I can think of no other word for it. He is able to section off a moment and a place and rope it away from the world and declare it Divine. Guy Gavriel Kay, the great Catholic authors and mystics down the centuries, Woolf in her own way, a few others- there are not so many who know this spell and understand the proper way to recite it. Even fewer of them do not require the assistance of a perfectly staged performance and a Wizard of Oz behind the curtain to achieve it. He's one of them. What is more, he has so many different kinds of rapture- some that stand apart from the rest in isolated glory, some that last a few paragraphs of a pause, and some that are just phrases woven into a surprisingly colloquial and conversational surrounding tale. He allows his 18 year old self to be excited about some conjecture that perhaps doesn't seem very important now, and lends his additional forty years of experience to help out. His other great power is a wonderful capacity for digression, footnotes and sidenotes. He has the sort of curiousity that seems to always pay off- adding to his ability to make an occasion out of stopping for lunch. If the trees are boring, well, let's talk about singing to ourselves in Latin and acting out Henry V on Dutch roads instead, if the German countryside's rustic Medieval charm cannot be further elaborated upon, why don't we talk about the Danubian school? First of all, I am jealous that he can do this. Second of all, it is always fascinating. He's just never, ever at a loss. The depth of knowledge he has to draw on (which, the flattering comparisons to Byronesque behavior aside, prove that books were some of his best friends, no matter what other ones he may have acquired) is just astounding. He couldn't create the atmosphere he does without formidable ingredients to draw on- luckily he works with only the best. Perhaps this is part of it too- he refuses to descend from the height on which he sits, or to consider a trip to the pub to nudge and wink more than the once or twice he is in the mood for that sort of thing. I got such a sense of Fermor from what he told me on the side, the way that he shaped this story. Which Fermor is of course the question. Sometimes it was old man Fermor shaping the bright young Fermor, at times it seemed like a remnant of the young Fermor broke through the careful old gentleman, whether he wanted him to or not- how artless was it? Was he consciously naïve? Was he overly careful? How much was a portrait of the artist as a young man, and how much was the young man in negatives himself? Of course near the end Fermor gives us a taste of the un-retouched voice of his 18 year old self and leaves us to judge. But perhaps that is merely selective, planted evidence as well. Whatever is the case, Fermor is one of the best artists of the Self that I've met, and certainly the one who seems to have worked on it the longest and the most thoroughly. We all of us have many selves on display, and without schizophrenia, it isn't often that our selves get to talk to each other with an audience around. He makes much of the memories that never were (the landmarks just a few miles out of his way he never knew about, the events he arrived just after or before, the art he did not properly appreciate), which for an narrative about 1930s Europe seems an appropriate topic. It's almost as if he had such an obligation to make what memories he could burn brightly- because he had been to a nearly fallen Eden that no one could go again. If his constant allusions to fairy tales, the Middle Ages, ancient myth and artwork irritate you somewhat or seem problematically racist/essentialist I would just say that Europe was robbed of a lot of Stories that no one wanted in the 20th century in favor of an attempt to return to Before. In the absence of history, the brightly painted knights and the Vermeer serving girls were what was left that one could talk about in order to attempt to understand why. Imperfect memory robs you, voluntarily or involuntarily.: "Apart from that glimpse of tramlines and slush, the mists of the Nibelungenlied might have risen from the Rhine bed and enveloped the town; and not only Mainz; the same vapours of oblivion have coiled upstream, enveloping Oppenheim, Worms and Mannheim on their way. I spent a night in each of them and only a few scattered fragments remain:… Lamplight shines through shields of crimson glass patterned with gold crescents and outlined in lead; but the arch that framed them is gone. And there are lost faces: a chimney sweep, a walrus moustache, a girl's long fair hair under a tam o'shanter. It is like reconstructing a brontosaur from half an eye socket and a basket full of bones." I mean, this is a travel book. It is firmly and gorgeously grounded in a sense of place. It is, in the end, about walking across Europe and having wacky adventures and picturesque scenes. But it is also about experimenting with literary forms, with the past and with the Self. It is about engaging with a history that was not yet ready to be history, telling friends about wacky adventures, about the power of stories and it is about an 18 year old boy growing up. There's a gleeful silliness that lurks under some of this, a deadly seriousness to other parts, a winking acknowledgement of melodrama, and a creation of it in successive paragraphs, without breaking a certain kind of consistency. It is a meditation on the role of the storyteller himself. How much of the storyteller is in the story, how much should be there? What would be there anyway, without him, and what needs him to make it real. Some storytellers outshine the story- Fermor is one of these. But I don't resent him for it. There are a lot of good stories in this book, but in the end, he's the best one. |

Review # 2 was written on 2011-06-02 00:00:00 David Umbenhower David UmbenhowerThis is about a European walking tour begun by the author in 1933. He was 18 at the time and his budget was £4 a month, sent poste restant to him along his route. The book's unusual intellectual depth derives from the fact that he did not write the memoir until much later in life. This first volume, of three, appeared in his 62nd year. Leigh Fermor's departure from London takes the form of a lengthy description of his steamer, the Stadthouder, pulling away from Irongate Wharf under Tower Bridge on a rainy night. His literary technique here is to slow the moment down through excess description as if to savor it. This is just the first spate of very rich description that one gets throughout. He naps in the pilot house and is in snowy Holland in a blink. Here everything reminds him of Dutch painting. On the third or fourth night he sleeps above a blacksmith's shop. Promptly at six he's awakened by the clanging hammer, the hiss of hot metal in water, the smell of singeing horn as a horse is shoed. Heading for the German border, he comes across a belfry and, almost reflexively, climbs it:The whole kingdom was revealed. The two great rivers loitered across [the landscape] with their scattering of ships and their barge processions and their tributaries. There were the polders and the dykes and the long willow-bordered canals, the heath and arable and pasture dotted with stationary and expectant cattle, windmills and farms and answering belfries, bare rookeries with their wheeling specks just within earshot and a castle or two, half-concealed among a ruffle of woods. (p.34) His trek across Germany comes at the very start of the Thousand Year Reich. Hitler has been Chancellor just nine months. The people he meets are wonderful. He picks up two fräuleins in Stuttgart--he was strikingly handsome--who don't let him go for days. The parents happen to be away at the time. There's a funny evening when one of the girls must attend a party held by a business associate of her father. The German host is a Nazi and a man of high, conspicuous style. His ghastly modern villa is deprecated at length. Leigh Fermor watches as the host hits on each young woman in turn, cornering them in his study, and is rejected by both. This does nothing for his standing among other guests. (He styles himself the young woman's cousin, named Brown.) His host introduces him around as the "English globetrotter," which PLF resents. Most amusing is their departure. To protect the girls' reputation he must tell the host he's staying at a nearby hotel, when of course he's sleeping on their sofa: We had to take care about conversation because of the chauffeur. A few minutes later, he was opening the door of the car with a flourish of his cockaded cap before the door of the hotel and after fake farewells, I strolled about the hall of the Graf Zeppelin for a last puff on the ogre [his host's] cigar. When the coast was clear I hared through the streets and into the lift and up to the flat. They were waiting with the door open and we burst into a dance. (p. 80) Then he's in Bavaria wrestling strapping peasants on beer hall floors for fun, losing his precious notebook, his walking stick, and waking "catatonic" with hangover, or, as it's called in Germany, katzenjammer. The holidays pass and on 11 February 1934 he turns 19. He undertakes a recapitulation of his reading at the time, much of it Latin and Greek, which left me envious of his failed classical education. Though he was a terrible student ' a scrapper and practical joker it seems ' he ended up a formidable linguist, who, only a few years later during the war, along with his unit--he was in uniform by then--successfully kidnapped a German general in Crete. This would make him a national war hero, but I rush ahead. In Austria, as in Germany, he has occasion, between his nights in peasants' stables and hutches, to find himself lodged amid extraordinary grandeur. He had the foresight to arrange a number of introductions on the continent. In Austria he fetches up at the schloss of K.u.K. Kämmerer u. Rittmeister i.R., Count Gräfin of the late dual monarchy. The count was old and frail. He resembled, a little, Max Beerbohm in later life, with a touch of Franz Joseph minus the white side-whiskers. I admired his attire, the soft buckskin knee-breeches and gleaming brogues and a gray and green loden jacket with horn buttons and green lapels. These were accompanied out-of-doors by the green felt hat with its curling blackcock's tail-feather which I had seen among a score of walking sticks in the hall. (p. 137) We move on to an assessment of the quintessential Austrian schloss. It myriad details are considered, as well as certain regional variations. The disquisition on German painting (Cranach, Bruegel, Altsdorfer, Dürer, etc.) has the righteous authoritative tone of Robert Hughes. Especially interesting is the author's point about the lush technique of the Italian Renaissance hardening into a grotesque and visceral style in the north due to the brutal wars of the period. (See C.V. Wedgwood's fine The Thirty Years War which he extols in a note.). We also get details of the Danube's history, its flora and fauna (including a predacious 15-foot catfish known as the Wels). The author's not infrequent late nights at the various inns along the way are colorful. The one five miles from Ybbs "was made of wood, leather or horn and the chandelier was an interlock of antlers." A tireless accordionist accompanied the singing and through the thickening haze of wine, even the soppiest songs sounded charming: 'Sag beim Abschied leise "Servus,"' 'Adieu, mein kleiner Gardeoffizier,' and 'In einer kleinen Konditorei.' . . . The one I liked most was the Andreas-Hofer-Lied, a moving lament for the great mountain leader of the Tyrolese against Napoleon's armies, executed in Mantua and mourned ever since. (p. 170) The section on the migrations of peoples I found particularly dense. One thing you have to say for PLF, he does not write down to his reader. He assumes you have much the same knowledge or educational grounding as he does, and for those of his generation this was by and large true. Always hovering is the horror of the Holocaust to come. It's 1934 after all. But it's not until he enters Köbölkut in the marches of Hungary, and finds himself among the roughhewn peasantry in a local church on Maunday Thursday, listening to the Tenebrae, then, in search of a bed for the night, when he finds himself talking to the local Jewish baker, that the weight of the inevitable hits the reader and the effect is is one of deep dread. The church had lost its tenebrous mystery. But, by the end of the service a compelling aura of extinction, emptiness and shrouded symbols pervaded the building. It spread through the village and over the surrounding fields. I could feel it even after Köbölkut had fallen below the horizon. The atmosphere of desolation carries far beyond the range of a tolling bell. (p. 299) I gave the book four stars because the style is very dense and I never quite acclimated to it. I find PLF here at times too humorless and didactic. There's a smell of the lamp, true, but there's also much that's wonderful. He's clearly drunk on the history of the Danube basin and he has a gift for making languages interesting on the page even for those who do not speak them. That cannot have been an easy task, but he does it. Particularly interesting was how one almost watches him pick up German, writing about the change of dialects along the way. There's so much more I'm not touching on. Bratislava and his friend there, Hans, the banker; the last-minute train trip with Hans to Prague in the snow, a backtrack to the only city on his 2000-plus mile route he does not enter on foot; his discussion the following morning with the Jewish baker's Hasidic heritage; the time he's held at gunpoint on the Austria-Czech border when he's thought to be a smuggler; his contemplative loitering on the bridge between Slovakia and Hungary, the Basilica of Esztergom looming overhead, the Danube rushing below. But for all it's verbal richness A Time of Gifts can be at times a bit of a slog. One never careers happily through it. One is always aware of the great erudition, the trumping vocabulary, etc. It is in the end like a cloying, too rich desert. If you're inclined to indulge, as many will be, (for the book is very highly regarded), so much the better for you. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!