|

|

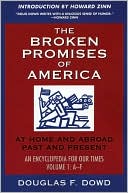

The average rating for The Broken Promises of "America" Volume 1: At Home and Abroad, Past and Present, An Encyclopedia for Our Times, Volume 1: A-L based on 2 reviews is 4.5 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2011-05-25 00:00:00 Karen Dirkson Karen DirksonIn Defense of Tradition is a book inasmuch as it is a collection of writings between two covers. But the topics covered, and the manner in which they are covered, vary as much as the mind of the man who wrote them and therefore lack an intentional cohesiveness. Nevertheless, Richard Weaver - an English teacher by profession, a rhetorician by reputation, a Southerner by birth, a philosopher, a socialist-turned-conservative, a historian, a social critic - brings all of these influences to bear in these "shorter writings" compiled by Ted. J Smith, III. Not only is the polymathic quality of Weaver's mind on display, but so too is its development and refinement. All of this makes categorizing, to say nothing of reviewing, the book a difficult task. Smith's selections for this book are Weaver's essays and speeches that have not previously been published in book form. In an attempt to overcome the aforementioned lack of cohesiveness, he groups them by topic, and then by sub-topic, and then orders them chronologically. In this way, Weaver's thoughts are presented in the most orderly way possible, but since they also cover three and a half decades, the reader will have to occasionally remind himself that turning the page forward has been a step backward in time. Smith begins the book with a biographical essay that is itself worth the price of the book. Weaver, for some unknown reason, has been particularly susceptible to myths about his life that, once uttered, seem invincible. The most common of these myths is that Weaver was such an anti-modernist that he refused to use machine labor on his farm in North Carolina, demanding that his mother plow it with a mule instead. Smith, however, shows that not only is there no record of this being true, but also that "farm" is a generous description for the 2-acre back yard in which the Weaver family kept a garden. Another myth is that Weaver, while a professor at the University of Chicago, was a friendless recluse who lived, as Russell Kirk said, "in a hotel room with the walls painted black." Here again, Smith shows that the story doesn't match reality. The origin of these myths isn't clear, nor is their purpose, but in opposition to the vision of Weaver as a grumpy hermit who did little else but condemn modernity, Smith writes, "Weaver was a kind, courteous, and principled gentleman of the old school, thoughtful and deliberate in his speech, powerful and incisive in his writing, and deeply committed to the restoration of truth and order in contemporary society." Smith is not alone in this analysis of Weaver's character, and understanding Weaver the man is helpful in understanding his opinions and analyses. This snapshot of Weaver segues nicely into the first section of his writings, titled "Life and Family." The essays in this group, primarily private letters and speeches, and newspaper columns written while Weaver was in college, are mostly forgettable. An exception is Weaver's autobiographical essay, "Up From Liberalism," in which Weaver describes his movement away from the socialist stance of his youth toward conservatism. Vital to this transition was Weaver's introduction to the thought of the Southern Agrarians during his time studying at Vanderbilt University. Weaver wrote that while he initially disagreed with the Agrarians, he found that he liked them personally, which was the exact opposite of his relationship with socialists, who he agreed with but disliked. He writes, "It began to dawn upon me uneasily that perhaps the right way to judge a movement was by the persons who made it up rather than by its rationalistic perfection and by the promises it held out. ...It would be a poor trade to give up a non-rational world in which you liked everybody for a rational one in which you liked nobody." While it would be easy to carry this standard for choosing a worldview too far, there's something to the idea that a movement made up of miserable or misery-inducing people is one that is best avoided. In the same essay, Weaver explains what he thinks the proper attitude towards political and social change should be. While admitting that his nature is one of "a reformer or even a subverter," Weaver states that due to the limitations of man's knowledge and ability to predict and control his environment, which includes his fellow man, "whatever is there is there with considerable force...and in a network of relationships which we have only partly deciphered. Therefore, make haste slowly." This is sound advice, particularly in a world increasingly given to experimentation and the destruction of tradition. "Nevertheless," he adds, "it is most important...to draw a line between respect for tradition because it is tradition and respect for it because it expresses a spreading mystery too great for our knowledge to compass. The first is merely an idolatry...which has engendered some of the most primitive, narrow, and harmful attitudes which the human race has shown. ...There can be no hope for good things from an attitude as negative as this. But the other attitude is reverential and creative at the same time; it worships the spirit rather than the graven image... Some things we have to change, but we must avoid changing out of hubris and senseless presumption. And always we have to keep in mind what man is supposed to be." This is a theme that Weaver returns to in later selections in the book. The second section is titled "The Critique of Modernity," and Weaver was certainly one of the 20th century's most strident critics of modernity. Especially, Weaver condemns scientism, in which everything (or at least everything worth knowing) is thought to be explainable and discoverable by science. In addition, Weaver criticizes what Kirk termed the "Cult of Progress," which operates on the assumption that everything new is better than everything old, simply by nature of being new. Weaver's criticisms of modernity are considerably more nuanced than some of his critics let on, and this section shows the basis of his concerns. For instance, he notes the effect that science and technology have had at making the world smaller, a fact usually celebrated in song and verse. However, Weaver writes that science in this area "has declared an implacable sort of warfare upon the unknown, upon space and time" which "makes us again wonder whether its aims are not hostile to our peace. It tends to set up a world of such brittle relationships that if one part gets a sharp knock, the whole flies to pieces. One certain result we can see is an increasing rigidification of our world. If there is a sneeze in Siberia, it disrupts something in Patagonia. The shock absorbers have been removed. We used to look upon space and time as cushions which protected us against phenomena we did not wish to intrude. But science seems to have declared war on both, and both are being cut down, so that everything has a new proximity." These lines were written well before the advent of social media, which has only increased the unhappiness that individuals feel not over what immediately affects their lives, but over what sensationalized story or opinion is trending. More problematic, Weaver thinks, is what the scientistic attitude does to the nature of man, which is mainly to deny that it exists. This, however, is fatal to ethics. Weaver writes that "in the absence of a vision or intuition of what man is supposed to be, you cannot show any ground why he should behave in one way rather than another, and ethics and rational politics go out the window." On the idea that modernity always represents progress over the past, Weaver writes, "Manifestly it is impossible to learn anything from the past if one adopts a criterion of value so simplistic and foolish. How simple things would be if development had been strictly linear and upward." But, "once we admit, as we have to admit, that some periods of achievement in the past have something to teach us, we are on our way toward acquiring the humility necessary for wisdom, for not all wisdom is new wisdom." Weaver also criticizes the modern view that culture is monolithic, noting that a culture "expresses the feelings of the people in that place and time, and it is always conscious of itself; that is to say, it can quickly recognize what is foreign to it." Weaver writes that a culture is exclusive, but that by using that term he is not referring "to any principle of class distinction or to that snobbishness with which the more cultivated sometimes look down on the less so. Those are totally different matters. The principle of exclusiveness of a culture is simply...an awareness...that it is a unity of feeling and outlook which makes its members different from outsiders." With that said, Weaver writes that unity is not the only, or even the highest, goal in society. "Unity means oneness," he writes. "The goal is harmony. Harmony is the fruitful co-existence together of things diversified." The third section contains Weaver's thoughts on education. Here again Weaver considers the modern approach to education, particularly as influenced by John Dewey, as a decline from the standards of the past. He writes that "we behold a situation in which, as the educational plants become larger and more finely appointed, what goes on in them becomes more diluted, less serious, less effective in training mind and character; and correspondingly what comes out of them becomes less equipped for the rigorous tasks of carrying forward an advanced civilization." Note that this was written before the campus riots of the 1960s and before the silly put-upon behavior of today's college students. But this section is not all criticism. Explaining what kind of education is needed, Weaver writes that real education is not telling students what to believe, but is rather teaching them to consider fundamental questions in a spirit of humility. He writes, "Wisdom is never taught directly; indoctrination often backfires; propaganda ends up by drawing contempt upon itself. The education that forms minds and wins converts to belief in truths is education in the arts and sciences which have brought our civilization into being, in the ideas and values which can be shown to give it unity, and in history, which is the actual story of our trials and triumphs." Section four is titled "Rhetoric & Sophistic." Weaver, notes Smith, was one of the top 5 American theoreticians of rhetoric in the 20th century, and this section captures his thoughts on the art of persuasion. The idea that is repeated several times is Weaver's conception of the four types of argument: the argument from circumstance, the argument from authority, the argument from cause-and-effect, and the argument from definition. Of these, Weaver believes the argument from definition, in which ideas and terms are given meaning and oriented to first principles, is superior, rhetorically and ethically. Weaver has a few interesting perspectives as it relates to argumentation. First, he notes that the "commonest trick of the propagandist in any age is name-calling," and he elaborates that this is essentially an argument from definition, although one in which the definition applied is usually false ("it looks good to the uncritical, but actually is not"). How true that remains today. Secondly, Weaver writes that the tendency to reduce complex effects to a single cause "has wide appeal because it ministers to the desire for simple diagnoses and easy solutions." Third, and most interesting, is Weaver's belief that the way a person frames an argument reflects their personal character. Weaver writes, "'As a man thinketh in his heart, so is he' says the Bible. ...we may translate this, 'As a man frames his arguments when he wants to persuade others, so he is morally and intellectually.' Once this truth is appreciated, you find that you can judge a man not only by the specific thing he asks for, but also by the way in which he asks for it. And the latter insight is sometimes very revealing." Section five is titled "The Humanities, Literature, and Language." Here Weaver mourns the relative decline in prestige of the study of humanities, particularly in the universities, which he sees as not only a civilizing force in society, but also a humanizing one, calling those who study them to consider the good in man without attempting to divinize him. He further notes the deterioration of language, and the cultural effects emanating therefrom. Section six is simply titled "Politics," and covers Weaver's overarching perspective on politics as well as his application of this political philosophy to specific topics of his time. Weaver is widely (and correctly) considered a conservative, but his brand of conservatism isn't easily classifiable. On the one hand, it wouldn't be inappropriate to call Weaver a traditionalist, but he certainly wasn't a traditionalist without qualification. Weaver said that the conservative was "something of a definer," who looked for essences and identified first principles. He writes, "Conservatives are traditionalists in the sense that they value the power of tradition as a great stabilizing force in society and as a means of effecting many things which laws could never effect or would effect more harshly. But they are not bound to tradition as the final arbiter of right and wrong. For that we will go to philosophy, in confidence that it will give ample support to the conservative view of man and institutions." Assessing the traditionalism of Kirk, with whom Weaver confesses broad agreement, he nevertheless cautions against relying too much on tradition and the veneration of our ancestors, noting that to do so we still need to determine which ancestors and which tradition to follow. Weaver was also much friendlier toward libertarianism than other traditionalists. He thought that conservative and libertarian beliefs were close enough that while they "may not overlap exactly, they do have an overlapping and they certainly are not in necessary conflict." He could "see nothing to keep [the conservative] from joining hands with the libertarian, who arrives at the same position by a different route, perhaps, but out of the same impulse to condemn arbitrary power." In expressing this belief, he writes that "the conservative in his proper character and role is a defender of liberty." Despite this, Weaver had reservations about some libertarian beliefs about the nature of society, believing that it was not as simple as saying that society was a collection of individuals, but rather that the individual and society were more co-dependent than that. Here his concern appears to be that libertarians left too much room for the atomization of the individual and the atrophy of social institutions. When it came to applying his political philosophy, there are two primary issues that Weaver addresses. The first is the threat of communism, and the right response in the face of it. It should be recalled that these essays were mostly written during the 1950s into the early 1960s, at the height of the Cold War. The interesting part of here is not so much Weaver's beliefs (he was, unsurprisingly, a foe of the collectivism and economic theory of communism), but the extent to which he lauded the American economic system and the common man as bulwarks against communism. These comments contrast starkly with Weaver's rather blistering criticism of "finance capitalism" and the "bourgeoisie" in his first book, Ideas Have Consequences. This likely indicates three things: that his criticism in that early work was qualified, that he had moderated his views over time, and that the specter of the creeping collectivism of communism was an impetus for that modification. Even so, it's a little striking to see Weaver giving what in some instances looks like a stump speech for the American way. Another, more difficult issue that Weaver addresses is the battle in the 50s and 60s over segregation. Here it will be remembered that Weaver was a Southerner, and while it would be inaccurate to say that he was a segregationist (he never discussed the issue, or race in general, in the gross terms that characterized segregationists), one does sense a certain defensiveness when he discusses what he considers a crusade against his home region. Weaver is best understood, I think, as an anti-forced integrationist - that is, he was not so much concerned with keeping people apart as he was with ensuring that they were together by voluntarily choice. He seems to have had defensible grounds for this position, seeing the attempts to force people to associate with each other as a violation of liberty and property, and a dangerous extension and centralization of government power. These are certainly valid concerns, especially considering that the crusade for equality via government, as today's headlines show, never ends once commenced. This brings to mind Robert Nisbet's observation that "The great difficulty with equality as a driving force is that it too easily moves from the worthy objective of smiting Philistine inequality, which is tyrannous and discriminatory, to the different objective of smiting mere differentiation of role and function." On this topic Weaver makes points that aren't terribly far away from writers like Thomas Sowell and Walter Williams, both of whom have discussed the problems resulting from using the state to improve relations between groups of people. Additionally, Weaver repeatedly writes that cultural improvement is necessary, but that it should come from ethical and moral appeals from the inside, not forcible change from without, implying that there were ways in which the South needed to change, and pointing to the methods that would effect it. Even so, I felt some uneasiness with Weaver's position, aware that his arguments could be used to justify unethical behavior. Weaver's personal opinions remain vague, since he never addresses segregation or race in such a head-on way that his exact ideas could be unequivocally pinned down. While I disagree with the notion that a person's entire body of work can be judged by his opinions on a single topic, and while there is much in Weaver's writing to suggest a commitment to the dignity of the individual regardless of race, there's enough here and in the final section that made me cautious of uncritically adopting his point of view on this and related matters. The final section, titled "The South," includes essays on Weaver's homeland. These essays are not an apology for the South, as Weaver criticizes it fairly heavily, though not for the usual reasons. The South, Weaver believes - with its hierarchies, its religiousness, and its clear delineation of expected behavior - was the American heir to the old European order. It was precisely this heritage that Weaver believes the South didn't understand, and failed to defend - before, during, and after the Civil War. Weaver makes a good case for the South's virtues, though his tendency to not address the South's obvious vices more directly might strike a non-Southerner (like me) as sweeping the dirt under the rug in order to present a cleaner picture. Certainly southern history, like all history, is more complicated that many are willing to admit, but the solution to oversimplified history isn't found in dodging the most important issues, even if they're one part of a larger story. That said, this section isn't entirely without merit and does contain some thought-provoking material. Overall, this is a fine book, and Weaver's reputation as a conscientious writer and thinker comes through unscathed. I wish that he were more consistent or clear on certain topics, but despite his imperfections (a condition which he shares with all humanity), Weaver left valuable resources to guide us as we seek to restore our culture. |

Review # 2 was written on 2009-08-19 00:00:00 Kesha Skaggs Kesha SkaggsWeaver, Richard M. In Defense of Tradition: Collected Shorter Writings of Richard M Weaver, 1929-1963. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 2000. Richard Weaver's legend was already secure when he wrote his brilliantly-titled Ideas Have Consequences. In this collection of essays we see Weaver the teacher, the professor. It's hard to say how modern American Conservatism would have emerged had it not been for Weaver. In a sense, Weaver may have passed the baton to Russell Kirk, from whom National Review took it (and likely ruined it). Section 1 highlights with Weaver's key essay "Up from Liberalism," wherein he describes his movement from a young college socialist (but I repeat myself) to a mature agrarian conservative. Why would someone like Weaver be interested in socialism? Aside from youthful naivete, it seems he was looking for an organic connection among humanity that doesn't reduce men to capital (ever heard of the phrase "Human Resources?" It should chill you). Of course, socialism can't deliver, mainly because academic socialists don't know how humanity acts. Weaver tells a funny story from college: "I remember how shocked I was when a member of this group suggested that we provide at our public rallies one of the 'hillbilly bands' which are often used to draw crowds and provide entertainments….I have since realized that the member was far more practically astute than I: the hillbilly music would undoubtedly have fetched more [people] than the austere exposition of the country's ills" (34-35). Change "socialist" to "intellectual conservative today" and the point stands. As socialism bankrupted Weaver began to see that society could be ordered around "the Agrarian ideal of the individual in contact with the rhythms of nature, of the small-property holding, and of the society of pluralistic organization" (37). From this Weaver would later take his stand (no pun intended) on the idea of "substance" or "the nature of things," yet he would not do so in the way of scholasticism which endlessly multiplied speculations and abstractions. He notes that it is "the intent of the radical to defy all substance, or to press it into forms conceived in his mind alone" (41). The ideological Marxist (both then and now, but much more efficiently now), knew that the best way to silence conservatives is to accuse society of "prejudice." What the Christ-hater meant is that any differentiation in society meant an ideological violence. The form of the fallacy used, argumentum ad ignorantium, "seeks to take advantage of an opponent by confusing what is abstractly possible with what is really possible" (92-93). Reviewing T. S. Eliot, Weaver examines what is and isn't culture. We never get an analytical definition, but Weaver does offer some fascinating, if only tantalizing, clues. A culture is an image through which our "being" comes through. It's often regional in focus (think of the oxymoron international culture). As such, "Cornbread or blueberry pie is more indicative of culture than is a multi-million dollar art gallery which is the creation of some philanthropist" (150). In line with his Ideas Have Consequences, Weaver assumes philosophical realism, yet his defense of essences is never center-stage, and so never belabored. He reminds us that "names are indexes to essences" (235), and essences are what form "permanent things" (against which the modern world is in full attack). From the middle of the book onward, Weaver engages in various book reviews dealing with literature, history, and the South. Whether they are two pages or twenty, they are a model in concise thinking. As he ends, he reminds us what it is to be a conservative (and what most popular conservatives have lost today). We defend the essences of permanent things. There is a hierarchical structure in the universe (albeit closer to aristocracy than today's crude religious patriarchy). Teaching How to Think Since Weaver was a professor of English composition, this section (228ff) could yield some valuable insights. Given that Weaver was a gifted prose artist, and given that he taught students how to write and think (rhetoric, in other words), what advice does he offer us today? The section is too good and too long for any adequate review. The reader is encouraged to digest Weaver's The Ethics of Rhetoric. Observations Weaver wasn't a shrill alarmist bemoaning how Communists are taking over the universities. They certainly are, but the issues are deeper. Conservatives are just as guilty (if only by incompetence rather than malice). Weaver notes of curricula that students learn "a fair introduction to the history--but not the substance--of literature and philosophy" (Weaver 34). Let's remain on this point. I knew a lot of history in college and in seminary I thought I knew a fair amount of theology, but I never once had a teacher engage in a socratic dialogue concerning the meaning of essence, etc. * Original sin puts the breaks on "democratic reasoning." "Democracy finds it difficult ever to say that man is wrong if he does things in large majorities" (44). * Liberal education is designed to make free men. It cultivates virtue and such virtue is "assimilated and grows into character through exercise, which means freedom of action in a world in which not all things are good" (198-199). Key Insights The technocracy (ruled today by the cult of Experts) makes it hard to be a person. "Man is an organism, not a mechanism; and the mechanical pacing of his life does harm to his human responses, which naturally follow a kind of free rhythm" (75). * "To divinize an institution is to make it eventually an idol, and an idol always demands tribute" (153). * "Wisdom is never taught directly; indoctrination often backfires; propaganda ends by drawing contempt upon itself" (227). * "Future teaches got trained not in what they were going to teach, but in how they should teach it, and that, I repeat, is a very limited curriculum" (223). |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!