|

|

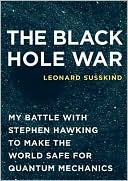

The average rating for Black Hole War: My Battle with Stephen Hawking to Make the World Safe for Quantum Mechanics based on 2 reviews is 3 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2018-03-22 00:00:00 Jane Doe Jane DoeIf you're into stuff like this, you can read the full review. Grain Alcohol Physicists: "The Black Hole War - My Battle with Stephen Hawking to Make the World Safe for Quantum Mechanics" by Leonard Susskind Mr. Leonard is head-over-heals enamoured of his views on string theory of being the underlying basis to a some greater reality and cannot in anyway be wrong. Einstein felt that way too, but there is a vast difference between Mr. Leonard and Einstein; most of Einstein's work could be for the most part tested in short order. The only detail left was gravitational waves which took instruments 100 years of development before being ready to capture their existence. With string theory the time scale before technology is advanced enough to test could be greater than the life of the universe. And of course if SUSY is not found at the LHC then string theory is so mathematically flexible that you can just claim "not enough energy". Maybe that is what Penrose is pissed at. The math puts forth unproven models as for example extra dimensions. No one sees this as puzzling but there is a huge chasm and string theorists fail to see it. Extra dimensions require faith. No way around it. The same faith one has in believing in a standard religion (I am all for religion). Religion transcends the physical but so do extra dimensions. They assume a fourth or fifth spatial dimension is as real as 3 dimensions without a physical way of seeing, feeling, testing or even imagining it. How is that for faith? If you're into shitty arguments regarding Black Holes, read on. |

Review # 2 was written on 2018-03-16 00:00:00 Hubertus Peter Hubertus PeterPeople like unified, completed pictures, and science books tend to go for that approach, typically some version of the Hero's Journey: the heroic scientist (sometimes also the narrator) encounters the fiendish problem, bravely engages it, goes through many trials and setbacks, perseveres, and eventually triumphs. But real life is messier. You're never at all sure what's going on while you're in the middle of the fight, and quite often you aren't even sure if you've won or not. This book pretends to be a Hero's Journey, but it's pretty clear that in fact it isn't. I enjoyed it for the opposite reason: it effectively conveyed the confusion and uncertainty of these would-be heroic enterprises, where you don't know who's a good guy and who's a bad guy, whether you're making progress or going backwards, whether your idea is a brilliant flash of inspiration or the most complete bullshit. We're somewhere in the middle of a transition period in physics, where people are painfully trying to sort out the contradictions inherent in the 20th century's two great breakthroughs, relativity and quantum mechanics. They just won't fit together. The story in The Black Hole War follows one thread, which engaged the attention of many of the world's best physicists for decades and is still anything but resolved. What happens when an observer falls into a black hole? What happens to the faint Hawking radiation that the black hole emits? Is information destroyed in this process, or somehow just very effectively scrambled? To what extent do observers outside the black hole see the same thing as observers falling into it? Black holes, it turns out, combine aspects of relativity and quantum mechanics in ways which do not allow people to ignore their mutual inconsistencies. Thinking about them is a kind of spiritual exercise, which one day may lead us to a new understanding of the most fundamental ideas in physics. Susskind does a good job of conveying the frustration of grappling with these extraordinarily treacherous questions. He has a long drawn out series of skirmishes with Stephen Hawking, where he tries to convince him of the correctness of his point of view and meets with determined resistance. Hawking eventually capitulates, as far as I can see mostly from exhaustion, to a bizarre argument which seems anything but conclusive. My understanding is that it's already been more or less dismissed, and the Black Hole War, far from ending in a victory for Susskind's faction, is still going on. But I didn't feel cheated; I understand more clearly now what the issues are in this strange conflict, and I'll be better placed to follow the dispatches from the front lines. Thank you Len, fine battlefield reporting. ________________________ [And on further consideration...] There's a claimed paradox which plays a major part in this book, and has been mentioned extensively elsewhere. Consider, says Susskind, what happens to an astronaut who falls into a very large black hole. From the point of view of someone a long way from the black hole, the astronaut will be fried to a crisp as they get closer to the event horizon. But from astronaut's own point of view, they will be fine. Since the black hole is very large, tidal forces will not be strong at the event horizon, and the Principle of Equivalence means that they won't notice anything special happening. This paradox is dramatized in the short story "Don't Forget Your Antigravity Pills". Well... Susskind says he gets plenty of crank mail from people who write to tell him they have black hole paradoxes all figured out. I am reluctant to join this unhappy band, but there is an obvious point I'm surprised not to see highlighted, and it's not mentioned either on any of the pages I found when I googled "what happens when you fall into a black hole". Tidal forces aren't the only thing that might kill you when you are in the extreme situation of falling into a supermassive black hole! There is also the problem of your velocity, which, as far as I can see, asymptotically approaches the speed of light as you near the event horizon. That means that any light travelling towards you will be blue-shifted to higher and higher frequencies, which only fail to become infinite because the quantum nature of light means that it will arrive as a finite number of discrete photons. We know there will be some such photons, due to Hawking radiation. The last few photons you get hit by before you reach the event horizon should have truly enormous energies - quite high enough that you will get burned to a crisp from your own perspective. What's wrong with this argument? Okay, okay, Professor Susskind... you pass my "good philosophy" test. That was such an interesting question that I have to start playing too. You win, and I'm giving you an extra star to show I mean it. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!