|

|

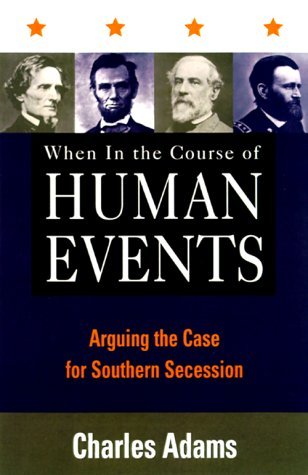

The average rating for When in the course of human events based on 2 reviews is 3 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2016-07-01 00:00:00 Michael Green Michael GreenThis book has a not-new thesis, beloved by Marxists and Charles Beard: that economic reasons were the real driver behind the Civil War. Actually, Charles Adams tells us that only one economic reason was the sole driver—increased tariffs dictated by the North. As with all ideologically driven analysis, this ignores that all complex happenings have complex causes. Compounded with Adams’ numerous gross falsehoods, obvious ignorance, and bad writing, the result is Not Fresh. I cannot speak with any authority to how much economic reasons had to do with the Civil War, although I can say with certainty that was only part of the reason the Civil War erupted. I suspect few rational people would argue that economic reasons were irrelevant. But I can speak with authority on legal matters and the structure of the American legal system, an analysis of which Adams heavily relies on to support his thesis, and in that regard Adams is comprehensively ignorant in a dishonest way. Adams, at the beginning of the book, spends a lot of time establishing the supposed illegitimacy of Lincoln’s behavior, unoriginally casting Lincoln as a Julius Caesar-type dictator. Adams puts great weight, 10% of the entire book, on a discussion of Ex Parte Merryman. This was an 1861 case in which the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Roger Taney, acting as a circuit judge (i.e., explicitly not in his Supreme Court role), granted a writ of habeas corpus to a man imprisoned in Maryland by the military for sedition. The military, and Lincoln, refused to comply, with Lincoln explaining the legal basis for his reasons to Congress a month later. Adams repeatedly and shrilly claims that Lincoln’s failure to obey Taney’s writ meant that Lincoln was undermining the entire system of American constitutional government by “refusing to obey a decision of the Supreme Court.” For many pages, Adams goes on in this vein, comparing Lincoln to Caesar crossing the Rubicon at least ten times and never acknowledging that there could be any doubt about the legal conclusion involved. But Ex Parte Merryman was NOT A SUPREME COURT DECISION. It was the act of a lower court judge acting “ex parte”—that is, without hearing from the parties involved. This is typical for a writ of habeas corpus, but an ex parte opinion from the Supreme Court itself has limited precedence, and the opinion of one justice of several, not even acting as a Supreme Court justice, has no Supreme Court precedential value at all. But Adams flatly denies all this, or does not understand it, and even bizarrely claims “Today, Taney’s opinion is studied in law school as one of the great decisions on constitutional law, with no dissenters.” Nothing could be farther from the truth—in fact, the core legal question involved (whether it is Congress, the President, or some combination of the two can suspend the writ of habeas corpus, which suspension is explicitly allowed in the Constitution) has never been settled by the Supreme Court. Lincoln, unsurprisingly, took the position that the President had that authority, which was not and is not an illegitimate position. Then Adams tells us that Lincoln’s response was to order the arrest of Taney, who only was not arrested because of the discretion of the arresting officer. But this is a conjecture supported by no historians at all; there is no evidence such a thing ever happened except the word of one man years later. It is the Civil War equivalent of claiming that the government is warehousing aliens at Area 51. Adams doesn’t say that—he treats the supposed arrest warrant as an acknowledged fact, though from his defensiveness you can tell that there is something wrong. In sum, the atrociousness of the facts and analysis in this chapter cannot be overstated. The rest of the book has some interesting sections—for example, on the British press’s reaction to the Civil War. But given the total falsehoods and biased selection of evidence related to Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus, there is no way for a non-expert to tell whether the rest of the book is similarly filled with falsehoods and cherry picking. But the rest of the book is undoubatedly filled with tendentious writing, constant propagandistic phrasing favoring the South, unbalanced analysis, and vitriol unbecoming in a supposed historian. For supposed historian is what Charles Adams is. He self-describes himself on the blurb of his book as a “the world’s leading historian of taxation.” I am not a slave to academic qualifications, but Adams appears to have none. It is hard to find information on him, but according to a 1993 newspaper article, he is “a former California lawyer who is a research historian at the University of Toronto,” and before that “taught history at the International College of the Cayman Islands.” The book prominently notes that it is the “Winner of the 2000 Paradigm Book Award.” I can find no reference to such an award except in connection with this book. The back cover has positive blurb quotes from four people from Emory, Auburn, USC and Florida Atlantic University. The first two are not from historians, but from a philosopher and a trustee who is not a teacher at all. The third is from an elderly historian who is a founder of the League of the South, a neo-confederate organization. The fourth, a short and anodyne quote, is from a historian about whom I can find little information. But none of this increases my trust in this book. I’m sure there’s a case to be made for some of Adams’s opinions, but he does himself and his positions no favors with this book. |

Review # 2 was written on 2011-03-21 00:00:00 Kenneth W Gardner Kenneth W Gardner“When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with one another; and to assume among the Powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect of the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. - That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, - That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish It …” [bold emphasis added] - Excerpt from the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America, 1776 As Americans, we pride ourselves on our love of a good rebel. Whether it’s John Hancock signing his name to the above cited document in a large and sweeping hand “So that John Bull could read it without his glasses”, Geronimo’s infamous leadership of the Chiricahua in open defiance of the US Army or even James Dean’s effortless portrayal of his iconic Rebel Without a Cause; we love ‘em all. Well … that’s not entirely true … we don’t much care for the Confederacy of the Southern States of America in the latter half of the 19th century. And why not? What is it that makes their rebellion so different from our other beloved rebels’? I guess I’m not really sure anymore. According to Charles Adams in his book When In the Course of Human Events, the South was well within their rights to secede from the union of independent states one century, two score and one decade ago. And he is not alone. At least not alone when it comes to 19th century thought. Many prominent 19th century Americans, and Europeans as well, believed in a states right to secession – especially in an independent union of sovereign states. Keep in mind, America was (at that point in its history) neither an empire nor a commonwealth. The sovereign states ultimately owed no allegiance to any nation, king or monarch. The Federal Government, according to the Declaration of Independence, derived its just powers “from the consent of the governed”. But what happens, as did in 1861, when citizens of those sovereign states no longer granted the Federal Government their consent? Well . . . according to Abraham Lincoln, they were to be imprisoned without trial, they were to have their property unceremoniously seized and/or destroyed and ultimately, they were to be killed as traitors. I would hardly call that “Government of the people, by the people and for the people” as Lincoln so ironically spouted in his sophistic yet revered Gettysburg Address. Mr. Adams, throughout his book, makes an extremely strong case for the right of southern secession. What’s more, he makes his case based on the founding documents of the United States of America, the laws of the land and even by the words of Abraham Lincoln himself – along with the likes of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Chief Justice Chase, Chief Justice Taney and on and on and on. So what went wrong? If secession was an obvious state’s right, why did the War Between the States even take place? Adams has an answer. And it’s not the answer that many may expect. Why did the Civil War take place? Simply put: “The Love of Money” butting heads with a generation “enamored of war”. Adams’ well researched answer to that often asked question echoes the thoughts of many including respected British writer and thinker Charles Dickens who took an interest in America’s troubles and noted that The American Civil War was, at its heart, “a fiscal quarrel.” It all came down to taxes and tariffs. Sound familiar? It should. Virtually every war in the history of the world can be traced back to disputes over little more than money or property. Why should the Civil War be any different? By 1861, the US government had raised the import tariff to an astoundingly harsh average of 47% (and with commodities such as iron, the tariff rose above 50%) with the passage of the Morrill Tariff. Due to Southern dependence on imported goods, this was effectively a non-uniform tax placed solely upon the South which ran counter to the Constitution itself. Analysis of the compromise tariffs of the 1830s and 1840s reveal that the total revenues to the Federal Government were approximately $107.5 million. Of that $107.5 million, the South paid approximately $90 million in duties, taxes and fees (over 83%) while the North only paid $17.5 million (17%) per annum. To make matters between the states even more strained, the North received the lion’s share of all Federal subsidies and benefit dollars - In effect, receiving the most while paying the least. That was why Fort Sumter (a tariff collection post) was the first battleground of the War Against Southern Independence. And it was also no coincidence that the businessmen on Wall Street and the wealthy Northern industrial tycoons were the money-men behind Lincoln’s invasion of the South. Southern secession would effectively put a stop to their illicit profiteering off the backs of Southerners. It’s also no wonder that a common saying in the Southern States became, “It’s the rich man’s war, and the poor man’s fight.” Throughout the pages of When In the Course of Human Events, Adams clearly and concisely makes the case for each and every one of his arguments. He even takes on many counter opinions and provides enough evidence to bring those opinions into serious question. The arguments are all well reasoned and amply discussed. And maybe the most interesting part of Adams’ work centers on the European views of the American Civil War. As outsiders, the Europeans provided an interesting third party view of the events without being blinded by the baggage that Americans brought with them regardless of what side they found themselves on. Many, if not most, Europeans viewed Lincoln in a harsher light than they did Napoleon himself. Each chapter of the book deals with another aspect of the war era whether it was before, during or after the action. And each chapter, while sometimes becoming a bit repetitive, still manages to provide interesting new evidence and fascinating writing pulled directly from the period by which to judge the ultimate reasons behind the penning of that horrible page in America’s still quite short history book. Adams’ writing is clear, crisp and simple. Having a tax writing background, he comes across as more than comfortable when dealing with the financial aspects of the causes behind the war while handling the history with a modicum of respect, and occasionally, with a touch of well deserved yet bitter sarcasm. It becomes obvious rather quickly that Charles Adams is not a fan of war – any war. That is to be admired. But, seriously, who is? Yet it’s refreshing to hear from a voice who seeks out the truth of things rather than simply swallowing the history as it was written by the victors of the struggle. Adams’ citing of opinion writing of the day, his inclusion of period newspaper articles and political cartoons and quotes from a multitude of key players and participants allows his audience the unique chance to slip inside the heads of those Americans who lived through that dark period and to understand their mindsets and motives as they witnessed the senseless destruction of the lives of some 630,000 of their young countrymen. I came away from this book with a new and interesting perspective on one of the most violent and devastating events our country has ever had the misfortune of suffering and I doubt I’ll ever view the events of that era in the same light again. In the interest of fairness, I must say there were a few times throughout this read where I found small issues with which I disagreed with Adams’ conclusions - though most of my disagreements stemmed from his moments of personal reflection rather than from his grasp of the history. And overall, I found his work to be a refreshingly honest look at the circumstances surrounding the war and the motives of all the parties involved. His unflinching look into the taboo issues of slavery and US race relations as a result of the Civil War and eventual Reconstruction were both fascinating and troubling – especially given today’s heightened politically correct climate. I won’t pretend to be a big fan of Adams’ prose, but the sheer amount of information, data and history he managed to put forth in this endeavor is, simply put, impressive despite his book’s diminutive size (some mere 230 pages). So, in conclusion, will this book convince you to ignore what your third grade history teacher taught you about Abraham Lincoln, William Seward, Salmon Chase, Daniel Webster and Union generals Grant, Sherman and Sheridan? Will you find yourself looking at Lincoln as less of a deified benevolent statesman seeking the preservation of democracy at any cost and more of a tyrant trampling the Bill of Rights in a breathtakingly bloodthirsty pursuit of slaughter against the South? Maybe. Maybe not. But I’ll tell you one thing: after reading When In the Course of Human Events, I find it more than just a little fitting that Mr. Lincoln has been memorialized as a larger than life god-king in a Greco-Roman temple of worship, seated high upon his royal throne, looking down his crooked nose upon his lowly American Subjects... |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!