|

|

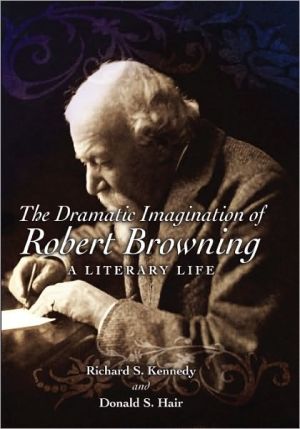

The average rating for The Dramatic Imagination of Robert Browning: A Literary Life based on 2 reviews is 3 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2009-12-14 00:00:00 Anthony Haskins Anthony HaskinsAt some point in life, the person of even modest ambition must confront his limitations. At the very least, time on earth is finite. Some balance between family and work must be struck, however lopsided, and as age creeps in, so must health be provisioned for. For the poet, middle age can be deceiving, as poetry can be written and written well in old age, and the desire to live life to the lees can incur a certain degree of distraction, especially for the poet who has achieved early success. For Yeats, heading into his 50th year, biographer R.F. Foster identifies the fulcrum, the inflection point at which Yeats would reconfigure his life in hopes of maximizing his impact and legacy. This is where his spellbinding and utterly captivating volume two begins. In the opening chapters, Yeats expands his friendship and collaboration with Ezra Pound. Rejected for the last time by Maud Gonne, Yeats considers marrying her daughter Isuelt, but ultimately and wisely chooses from Pound's London, courting the young Englishwoman Georgie Hyde-Lees, who serves for several years as Yeats' personal medium before switching jobs to child-rearer, personal secretary, and eldercare provider--the last being the inevitable result of marrying a woman less than half your age. Foster documents other shrewd decisions by Yeats. He capitalizes on the Irish War of Independence and resulting Free State with timely poetry and brief service as a senator, which he uses to centralize his literary power in Dublin and place himself at the head of various literary bodies and salons. When his health declines, he decisively bows out and spends more time abroad, starting with Pound's slice of expat Rappallo, Italy. His political views also show a man ruthlessly marshalling his slowing energies, as he attempts to juice himself up with fascism in the last decade of his life, including a dalliance with the Irish Blueshirts, an Irish right-wing militia infatuated with Mussolini. Yeats never succumbs to antisemitism or full-throat Nazism, but grows increasingly nasty--and oddly productive--by viewing Ireland's history and politics along racial and caste divides. While it is sad to see him seduced by some of the worst and most vile ideas the world has ever known, the impact on his poetry will always be a matter of debate. Yeats is a complex intelligence, and the belligerent man produced over his last two decades some of the finest poems of the 20th century, such as "Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen", "Leda and the Swan", "Sailing to Byzantium", "Byzantium", "Lapis Lazuli", "Cuchulain Comforted", and "Under Ben Bulben". These poems betray increasing whifs of Modernism's racial nationalism, the poison ideology that broke Pound's mind and tainted Eliot's soul. But Yeat's Romanticism never really succumbed. The wellspring of creativity, faith, and self-discovery keep renewing themselves even as Yeats faces his own sickness unto death. Foster, without explicitly stating it, manifestly advances the argument that old Yeats is best Yeats. Indeed, compared to volume one, Foster is more willing to provide gloss, counterbalancing his own judgement against major critical reaction of the time. Context is ample from letters, drafts, and personal circumstances leading to each major poem. The genesis of each poetry book--The Tower, The Winding Stair, A Vision, Last Poems--are given in detail. Yeats' second tour in the States is marvelously chronicled; Foster excerpts letters and notes taken from lecture attendees and socialites, plucking from sources I surmise were previously unheard of. Foster's appetite for primary-source material is all-encompassing. It's like reading from inside a cyclone. Foster gives us the dirt, too. Yeats makes a hash of his charge as editor of The Oxford Book of Modern Verse, including too much of poetry of friends, facilitators, or lovers, while committing serious and glaring omissions. Family friend and minor light Oliver St. John Gogarty is quoted as remarking, "What right have I to figure so bulkily?" Thanks to Foster, we can see exactly how Yeats' social, sexual, and financial well-being depended on those he lavished pages on, and how he felt absolutely no compunction to be "objective". So little has changed since his era of poet-editors and our own. We are shown Yeats' sexual powers failing in his waning years, and his desperate attempts to keep his mojo working as he plies his favors in literary and spiritualist London, conjuring a few women with the willingness and financial means to put up with him while he wife looks on bemusedly from a distance. Foster takes the time to write his own cycle of elegies for Yeats' friends--the death of Lady Gregory and George Russell are handled with special depth and understanding. When it is the Arch-Poet's turn, Foster stays with the plot until the very end. No spoilers here, but it is clear Foster has difficulty giving up what has been an epic vigil. |

Review # 2 was written on 2009-12-14 00:00:00 Matthew MASON Matthew MASONVolume II, and here Yeats has become the grand old man, the central figure of modern Irish literature and drama. There is an enormous amount of detail about the creation and productions of the Abbey Theatre. It is very possible that might be way too much for many readers. But through it all, and through all of the messiness of the Irish revolution and Civil War, the poems kept coming. Yes, as Foster shows us, many of them are tied to the moments in history, or Yeats' adventures in the occult, and become clearer once all that is explained by the biographer. But the poems still have their connections to readers -- does "The Second Coming," for instance need to be explained? No, but the explanations offer another dimension. And then there is the inevitable decline of old age. Yeats kept working very close to the dark, much closer than most poets. He clearly had some ideal image of "the poem." He kept looking for it right up to the end. There was a real joy in reading these two volumes, all the hundreds and hundreds of pages in them. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!