|

|

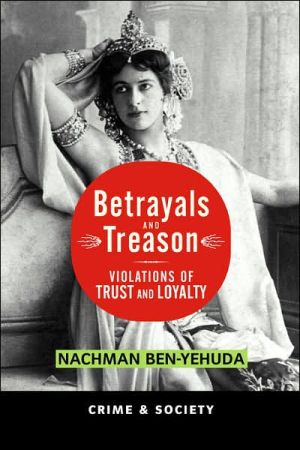

The average rating for Betrayals And Treason based on 2 reviews is 3 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2016-01-14 00:00:00 Paul L. Boyko Paul L. BoykoFor decades Professor John Keegan has been one of my favorite military go to historians. I could easily be one of his squealing fainting fans. With sadness I must report that Intelligence in War is not up to his standard and cannot be recommended. His case study methodology, elsewhere very illuminating; fails to fully serve this topic. At least some level of quantitative research would have helped to save this book. The first warnings are in the introduction when he admits that he is not well trained in the very large field of Military Intelligence. Not in itself a fatal limitation, but nothing that follows indicated that he overcame his limitation. Next he notes that in any number of fictional examples of espionage and spy books, the success or failure by the agents do not end the war or save the planet or whatever his criteria. Never mind that fictional spies save the world so often that the trope itself has become a joke. Fictional spies are always saving the world. For the more realistic examples of fictional espionage work blaming the spy for not changing history is like blaming a rifle company for failing to end an entire war. The example of the rifle company is deliberate. It is unrealistic to expect intelligence alone to be author of victory. Who has what soldiers where, after the battles are fought that most determines who has won the war. Everything else is more or less important, and by implication more or less incidental. The research question: What are the limitations of wartime intelligence? is valid. The professor's examination of the question is insufficient. Military Intelligence in its broadest definition can so inform the possessing nation that policy level decisions favor peace or war. This is what the U2 flights over Cuba achieved over Cuba. Their refusal to believe intelligence lead the Japanese to launch a war against the western nations and the US. How many wars have been avoided or launched based on pre-war intelligence assessments is a question never properly researched by John Keegan. If the above examples are accepted as absolute fact, there is no reason to believe that the outcomes of each example had to be: a peaceful resolution of Soviet Russia's attempt to place nuclear missiles minutes away from the US; or the stunning surprise attack on a vulnerable Pearl Harbor. It is just as valid to argue that it was the limitations on Japans relative economic and industrial capacity that most directly resulted in Japan's ultimate defeat. Do we now need a new case study called the Supplies in War, to document the value and limitations of supplies? Can we make a similar case for moral, or religion or paymasters or head gear? The point is that intelligence is an input. It is a tool. It is a part of a larger set of facts. A good general makes do with what is available at the time of battle. The same good general will have seen to it that his subordinates, including those with little or no access to the full intelligence briefing are best picked and placed to make the best decisions, given what they know at decision making time. Battle, can be conceived of as the sum of numerous smaller engagements. The relative will, training, equipage, and a inventory of tangibles and intangibles may be the immediate predictor of individual or collective outcomes. What most good generald understand is the relative importance of Luck. (Attributed to many including Gen. Eisenhower: 'I would rather a lucky general than a smart general"). What the best generals do is to work to improve or make their own luck. One, and only one of the tools for making luck is good, accurate, properly analyzed intelligence. It is telling that Keegan recognizes both the value of luck and quality soldiering but never quotes the best of the strategists on these topics. It is a major failing of the book that his book is uninformed by Sun Tzu. Even a few quotes would prove that he had made the effort to use research to augment his lack of depth on this subject. Attributed to or directly quoted from Sun Tzu: If you know the enemy and know yourself you need not fear the results of a hundred battles. Thus, what enables the wise sovereign and the good general to strike and conquer, and achieve things beyond the reach of ordinary men, is FOREKNOWLEDGE. Hence the use of spies, of whom there are five classes: (1) Local spies; (2) inward spies; (3) converted spies; (4) doomed spies; (5) surviving spies. When these five kinds of spy are all at work, none can discover the secret system. This is called "divine manipulation of the threads." It is the sovereign's most precious faculty. |

Review # 2 was written on 2017-11-21 00:00:00 Crystal Farney Crystal FarneyI'm not going to pretend like this will be an unbiased review. I am a huge Keegan fan and have read five of his other books. Keegan's method, one of which I am particularly fond, attempts to give the reader a broader understanding of military history. This is not done by sketching an overall connective and encompassing outline but instead by taking a few slices from different eras and showing how they fit into the larger history. Both the small and large scale are needed to interpret and comprehend the other fully. In this work, he starts with Nelson in 1798 and essentially ends with the Falklands War. He touches on Al-Qaeda but not much history is given. As I have come to expect from him, Keegan writes with both clarity and density in 'Intelligence in War'. I had to resist the urge to highlight entire pages. Even for the events of which I was knowledgeable, he added detail and analysis that was enlightening. I read a book entirely on the Falklands War and yet his partial chapter on it added details I didn't know. With all this being said, let me add some reflections on the book. 1) The book is heavy on the naval side. This isn't necessarily a bad thing; I find naval warfare fascinating. But I do wonder if it skews the analysis. Perhaps it would be worth splitting it into two volumes: one for naval and the other for land operations. I will return to the scope of the book later. But as it stands, there are chapters on The Mediterranean Campaign of 1798, von Spee's East Asia Squadron, The Battle of Midway, The Battle of the Atlantic, and a portion of the last chapter on The Falklands War. Land campaigns covered are only Shenandoah Valley and Crete. The hunt for the V1/V2 programs doesn't fit into either category neatly. Maybe it could be considered an air campaign. 2) It is also heavy on the modern side; four of the chapters are from WWII. His other books tend to have a better balance from different eras. Part of his point seems to be that useful intelligence was almost non-existent before electronic means of transmitting data. Maybe he is correct here, particularly from a strategic viewpoint, but this leads to my next point: 3) His definition of military intelligence seems rather narrow. I think the book does a good job of creating skepticism towards what might be a mythologized form of military intelligence: a key piece of information is discovered and a general alters his battle order last minute to seize victory. And to be fair, he does specify that he is only referring to operational intelligence. But why not speak of intelligence more broadly? I wonder if Keegan's theme is aimed at an attitude much more prevalent in the UK than the US. After all, the "WWII was won with American steel, British intelligence, and Russian blood" is still repeated ad nauseam today. Perhaps in Britain the idea of intelligence equaling victory is popular. Otherwise, I wonder who holds the view he argues against. I have heard that human intelligence needed/needs to be rediscovered in the war on terror but he agrees that, in this case, good intelligence will be invaluable. And hence, point 4. 4) While the war of terror has a larger scope, it is not fundamentally different from a whole host of wars throughout history. By acting like the GWOT introduces some new scenario where intelligence is of utmost importance ignores the entire history of small wars, insurgencies, and guerilla strategies. He even mentions in passing that these types of wars in the second half of the 20th century involved more of the world's population than World War II. Keegan seems to completely sideline half of military history, which is most notable because it is precisely the type of conflict in which intelligence is a primary asset. This omission, in my opinion, weakens the book far more than the other issues previously mentioned. Keegan's book offers a great deal of knowledge on battles or operations unknown to many readers. He writes with lucidity and depth about the slices of history he highlights and I would recommend the book to anyone interested in military history. However, unlike many of his other books, I do not feel that these slices are a good representation of the overall picture and I am not convinced of his overarching thesis. Actually, I should be more specific. I'm unclear about exactly how far he wants to push his thesis. Does intelligence alone win wars? Of course not, but no one is arguing that as far as I can see. So how useful is military intelligence? Not very, seems to be Keegan's answer. But I think his scope is strangely still too limited and the framing too restrictive for a satisfying answer. Final note: this was written in 2002, so be prepared for some remarks on Iraq that have aged, let's say, quite poorly |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!