|

|

The average rating for James and Bradley based on 2 reviews is 4 stars.

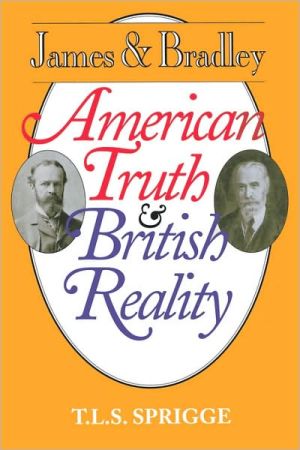

Review # 1 was written on 2016-10-05 00:00:00 Jeremy Englund Jeremy EnglundSprigge on James and Bradley I became interested in Timothy Sprigge's book, "James and Bradley: American Truth & British Reality" (1993) for two reasons. The first is my longstanding interest in American pragmatism and its relationship to American idealism as exemplified in the work and friendship of William James and Josiah Royce. The second is my related interest in philosophical religion. I had earlier read Sprigge's 2006 book, "The God of Metaphysics" which dealt beautifully with both these matters and led me to his study of James and Bradley. The Scottish philosopher T.L.S. Sprigge (1937 -- 2007) taught for many years at the University of Edinburgh. He was regarded by his peers as eccentric and as something of an anachronism due to his commitment to an idealistic philosophical absolutism -- very simply that reality is ultimately spiritual and consists of one all-inclusive mind or Absolute. This doctrine was much alive at the time of James and Bradley but was quickly falling out of philosophical fashion through the criticisms of Bertrand Russell and others. American pragmatism and its understanding of truth would also receive heavy criticism from Russell and his successors in analytic philosophy. Pragmatism has experienced a resurgence of interest in recent years which has not extended to philosophical idealism. In his book, Sprigge sees the American William James (1842 -- 1910) and the British F.H. Bradley (1846 -- 1924) as the dominating philosophers of their time and as the thinkers with the most to teach the present day. The two philosophers corresponded, referred to one another in their writings, and exchanged a series of articles, but they never met. Their two philosophies are often considered far apart, with James' alleged pragmatic understanding of truth as "what works" and Bradley's Absolute far removed from any practicality. Sprigge argues that the thought of James and Bradley has more in common than is sometimes supposed. He endeavors in part to synthesize the work of the two philosophers and to show the lasting value of what they hold in common. He also tries to identify and to assess issues on which they differed. In addition to a historical study of James and Bradley, the book also is an exposition in its own right of Sprigge's philosophy. The book is organized in two large sections, the first devoted to James and the second devoted to Bradley. This approach allows for a detailed, thorough approach to each of these thinkers but it also results in a tendency to lose sight of the comparison and relationship between the two and to focus on James and Bradley individually. In both parts, Sprigge examines the positions of his philosophers on the subjects of knowledge, reality, truth, and other large metaphysical concerns. He uses the techniques of analytic philosophy to draw distinctions and to develop possible alternative interpretations of controversial points. With respect to both James and Bradley, Sprigge often tries to help out and expand their insights. When he finds a stated position of argument less than convincing, Sprigge often works to modify it slightly to identify and defend the critical point under discussion. Most obviously, he works valiantly to defend both James and Bradley from the criticisms of analytic philosophy. Readers will need to decide for themselves the extent to which his efforts succeed. The arguments are difficult and extended, more so in the case of Bradley, who for the most part is Sprigge's philosophical guide, than of James. The discussion of James is the more accessible part of the book in part because James' writings are more likely to be familiar to readers. Sprigge is an insightful reader and student of James, and his discussion taught me a great deal. Sprigge's large point is that there is much more to James than pragmatism, difficult and important as pragmatism is. Sprigge sees James as a metaphysician, particularly in his late works such as "A Pluralistic Universe" rather than as a hard-headed scientific thinker. He sees the metaphysical James as teaching a form of experientialism as the basis of reality which is close to the idealism of Bradley and to that of Royce. James was driven by the need to provide a spiritual understanding of reality rather than be left only with the world of the natural sciences. James rejected vigorously, however, the monism and absolutism of idealism in favor of a doctrine of pluralism which he believed was necessary to understand and respect the autonomy of individuals and to deal with the problem of evil resulting from absolute idealism and monism. Sprigge's discussion ranges over James' work, including the "Principles of Psychology" which receives extensive consideration, the works on pragmatism, the books and essays developing the doctrine of radical empiricism and, in the culminating sections, James' views on religion set out primarily in "The Varieties of Religious Experience." Sprigge's treatment of Bradley, in its turn, discusses his opposition to understanding reality in purely conceptual rather than experiential terms, which he shares with James and with Henri Bergson. (Late in his life, James wrote a short essay titled "Bradley or Bergson?") Bradley remains a bristlingly difficult thinker. Sprigge tries to expound and to defend with modifications Bradley's views on the experiential, idealistic nature of reality, philosophical monism, the doctrine of internal relations, eternalism and the claimed unreality of time and more. The discussion becomes much more than a consideration of allegedly discredited teachings through Sprigge's engagement and discussion of competing and contemporary positions, including, among other things, the work of Quine, Russell, Rescher, Whitehead, Hartshorne, and the phenomenologist Edmund Husserl, among many others. The goal is to show how much of Bradley may be restated in the face of modern criticism and rejection of his work. Sprigge offers extended discussions of Bradley's doctrine of internal relations which endeavor to show how Russell's logical criticism of some interpretations of this doctrine may have missed the mark. Sprigge also presents an extended philosophical discussion about the nature of time and defends a form of the doctrine of eternalism (the past, present, future exist as part of a timeless whole) derived from Bradley. In the final section of the book. Sprigge summarizes his conclusions about what James and Bradley share, where they differ, and how their thought might be synthesized. Sprigge writes: "We have now surveyed the main teaching of both James and Bradley on truth and reality. In the process I have said most of what I have to say as to the way in which the ideas of these two thinkers, usually considered diametrically opposed, share many main premises and some main conclusions, while the contrasts between their views are all the more interesting just because they share so much. I have also indicated my own acceptance of the bulk of what they have in common and tried to persuade the reader of its rightness. Anyone who agrees with me on these points will agree that one of the great choices in philosophy can be put in the form of 'James or Bradley?' that is as the choice between a monistic or a pluralistic form of panexperientialism." (p.573) Sprigge argues that where the two thinkers differ Bradley is more nearly right on the broad picture while James is more insightful on the details of experience. Thus, Sprigge concludes: "Though I accept the basic monism of Bradley and thus his overall characterization of the world, I am in greater sympathy with James on most points of greater detail, for example on the character of the stream of consciousness, on his final panpsychist view of nature, and on the nature of moral sensitivity. In short, while I think Bradley right upon the whole about the whole, I think James right in very large part about the parts. So even if that would hardly please James, I think a Bradleyan account of the universe can only stand when filled out and qualified in Jamseian ways. And James remains its best critic and his philosophy the best alternative." (p.583) Sprigge's discussion and conclusions remain outside the mainstream of contemporary philosophical thinking, but the nature of philosophy is such that the dissenting character of the work does not render it wrong or without value. The book is mixed, in my view, with much that is insightful and much that is labored. I agree with Sprigge that there is much to be learned from James' pragmatism and later metaphysics and from Bradley's monism if not from his absolute idealism. A sense of the interconnectedness of reality as opposed to individuation as at the heart of this book. This long and difficult book will be of interest to serious students of philosophy with an interest in classical American philosophy and in the idealist philosophical approach. Robin Friedman |

Review # 2 was written on 2015-08-19 00:00:00 Anthony Sims Anthony SimsPaul Redding's Analytic Philosophy and the Return of Hegelian Thought, APRHT, is a systematic appraisal of the philosophically sophisticated Pittsburgh School readings of Hegel by Robert Brandom and John McDowell. While this would seem to imply that the work is derivative of the dominant analytic secondary literature on Hegel this is not true in the case of APRHT. The book makes several valuable contributions to contemporary Hegel scholarship. Some of these are: i> Bringing out the unity of lower-order singular perceptual cognitions and higher-order universal conceptual cognitions in Hegel's work, contra Brandom's account in which socially instituted conceptual norms are both necessary and sufficient to robustly determine the content of perceptual cognitions. ii> Rehabilitating Hegel's metaphysical claim of equivalence between what is conceptually cognisable and what actually is, by showing how Hegel cashes out the ontological status of higher-order regulative epistemic concepts in terms of the role they play in determining the semantics of lower-order perceptual cognitions. iii> Revealing Hegel's organizing principle of "cognitive contextualism" which allows him to deploy different logical systems for inquiry in different domains. iv> Showing that the learned confusion about Hegel's notion of determinate negation, or negation of negation, in the literature stems from Hegel's use of the Aristotelian term logical notion of negation, rather than the truth functional negation operator used in modern propositional logics to develop the mechanics of determinate negation. Points iii> and iv> are vital because they hit a deep vein in Hegel's work, providing a uniquely illuminating insight into Hegel's turgid and sometimes equivocal discourse, which uses term logic to talk about perceptual cognitions and propositional logic to talk about conceptual cognitions. This distinction also tells us where exactly the Pittsburgh School Neo-Hegelians' interpretations of Hegel betray the metaphysical ambitions of Hegelianism. For, term logical locutions may be negated in two ways: firstly one may negate the subject of the statement, secondly one may negate the predicate which is applied to the subject in the statement. While, propositional logical locutions can only be negated by treating the entire statement as false if true, or true if false. The upshot is that perceptual cognitions, in which negation can apply to either the subject or the predicate, are mediated for each individual by his adherence to epistemic norms endorsed by his community. While conceptual cognitions are mediated by each individual's ability to defend his claims when they are contested by others who have equal right to an opinion on the matter in virtue of their common endorsement of the norms prescribed by the recognitive community. The asymmetry of the fallible, top-down, lower-order perceptual cognitions of individuals with respect to the authoritative, bottom-up, higher-order regulative conceptual cognitions of the recognitive community to which they are answerable is what sets up the stage for Hegel's daedal methodological innovation: the dialectic. In summary, this work is essential reading for anyone interested in Hegel, Kant, Brandom, McDowell, analytic philosophy, and normative functionalism. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!