|

|

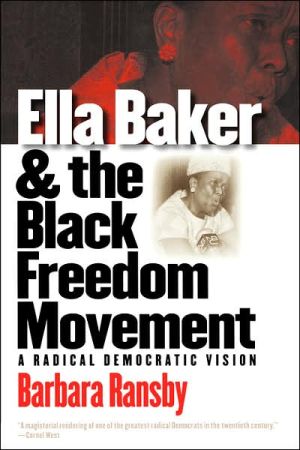

The average rating for Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (Gender and American Culture Series) based on 2 reviews is 5 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2012-06-10 00:00:00 Ruth Locke Ruth LockeFor decades, the name of Ella Baker has lingered along the margins of my thinking about the intersection of popular education disposition and political organizing processes. When the question of an radical democratic practice indigenous to the United States, I would consistently cite Myles Horton, Grace Lee Boggs, Ella Baker and the numerous radical pedagogy practices in the Black Freedom Movement. Call it a prejudice of theory, I never took the time to actually research Baker's life in much detail due to the simple fact that unlike most radical pedagogues, Baker never wrote a book to codify her ideas. A search of the library index will reveal many books about the civil rights movement and SNCC in particular that have a dedicated chapter on Baker. But with the exception of Joanne Grant's "Ella Baker: Freedom Bound" from 1998, there's been no thorough and exhaustive study of Baker's life and thought. This fact is all the more startling considering how many generations of organizers, educators, and radical intellectuals have attributed to Baker the status of architect (or master weaver) of the civil rights movement and participatory democracy in the United States. Barbara Ransby's 2003 intellectual biography of Baker seeks to correct that omission. As I read Ransby's book I consistently confronted my own prejudices about what constitutes political theory. For better or for worse, I feel like I have been trained to only recognize political thought when it is presented as a set of abstract political theoretical propositions. Of course, as has been argued for decades, this model of knowledge invariable privileges very specific experiences and histories, specifically a European male perspective. But more than that, such models of political thought reproduce the prioritizing of thought and ideas over experience and practice -- in other words, the Eurological model of political thought breaks the dialectic inherent to praxis. Ransby treads the fine line between providing a detailed account of Ella Baker's life and drawing from that life the lessons of a lived radical democracy. I say all of this because it occurs to be that in an age where radical thought grows increasingly sterile, "Ella Baker & the Black Freedom Movement" is probably one of the most important books on political theory I have ever read. The fact that it in everyway departs from the model of contemporary radical philosophy demonstrates the urgency of its argument; that theory and lived experience need to be in dialogue if our ideas are to have any meaningful consequence in the world. A central theme of Ransby's book is the profound dissymmetry between Baker's vision of democratic action and the orientations of the mainstream civil rights leadership. Here Ransby is able to fully develop the now-famous philosophical opposition between Martin Luther King Jr. and Ella Baker. Based on the notion of "racial uplift", King and the civil rights leadership were convinced that the protagonist of the movement needed to be the black middle class. Accepting the American ideology of petite bourgeois respectability, organizations like the NAACP and SCLC presented an image of black middle class demanding their rights. The voice of that demand, therefore, would come from the clergy; a strata of black society that tended to have greater access to education and middle class opportunity. It was no accident that a leadership based the clergy would also equate civil rights struggle with patriarchy. Baker, however, argued for a different model of protagonism. Ransby locates Baker's early life as deeply informed by the role of women missionaries in the black church. While often middle class themselves, these women functioned entirely differently from the male clergy. For these women, the work of the church bound together the personal social circles of women, providing for the needs of poor in the community, and advocating for the poor within the power structures of the community. As Baker matured in the fulcrum of the Harlem Renaissance and the subsequent Great Depression, her own worldview moved further away from a notion of charity to a radical understanding of the poor as protagonists in their own struggles. Never confused about her own identifications, Baker then saw her role as an organizer and educator as one who identified and nurtured the fighting spirit and democratic possibilities within the lives of the poor. As a consequence of this position, solidarity assumes a different structure from that of "racial uplift." Seen as rich in experience and political analysis, the poor no longer need the middle class to speak for them. The organizer, instead, learns to be silence, to ask questions, to listen, and to bring resources and networks to the communities in the closest proximity to the violence of racial and economic exploitation. As Ransby demonstrates over and again, a politics built upon the protagonism of the poor has implications beyond a class analysis of racism. It demands a different practice and analysis of gender from middle class normativity. Here we see how Baker's life exemplified this fact. It is no accident that in the context of SNCC, the organization where Baker had the most influence institutionally, the leadership role of women was unparalleled by any other national civil rights organization. Ransby's biography of Baker contains many other thematic gems useful for a theory of political organizing. But beyond theory, perhaps the book makes its greatest impact in how it suggests a different way of being in the world. Over and again Ransby stresses how for Baker a movement exists as a web of personal social relationships. Those relationships span decades as ever changing constellations of organizations and resources consistently return to the same networks of friends and tender comrades. Baker eschewed partisanship in the midst of cold war terror (sometimes with more or less consistency). For her, the only partisanship worth adhering to was the movement itself. And here, the movement for Baker was always a class-based understanding of racism and struggle. The liberation of the poor meant the liberation of all. The aim of the struggle, as Ransby argues, was to understand the historical basis of exclusion. Organizing did not mean simple halting those exclusions but to reverse them. Such a reversal suggested not only the destruction of the white power structure. It also meant the end of middle class privilege and arrogance. |

Review # 2 was written on 2015-01-10 00:00:00 Hilliard Smith Hilliard SmithI wish there was more emphasis and research into Ella's political development and explanation of who she was influenced by. There was an overabundance of biographical details. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!