|

|

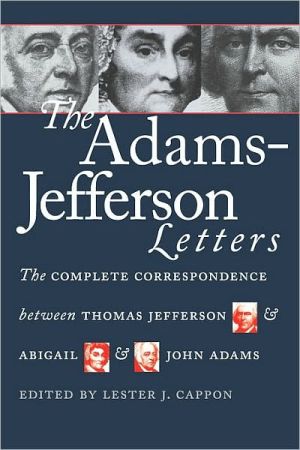

The average rating for The Adams-Jefferson Letters: The Complete Correspondence Between Thomas Jefferson and Abigail and John Adams based on 2 reviews is 5 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2012-11-22 00:00:00 Milo Milic Milo MilicThere are only a few people in the world today who have both patience and the inclination to read 600 pages worth of 200-year-old letters. If you are one of these people, do yourself a favor and read this book now. If you are not one of these people, try really really hard to become one of these people and read this book now. And if you can't possibly imagine ever being the kind of person who reads this kind of book, then do the rest of us a favor and don't go all over the Internet popping off about what "The Founding Fathers" believed about stuff based on something that you heard on the radio. Because it is probably a lot more complicated than that. Lester J. Cappon's Adams-Jefferson letters were first published in two expensive, hardbound volumes in 1959. Cappon was a historian and professional archivist who worked with these documents all of his life, and his edition is a model of good scholarship: it is thorough, it footnotes nearly everything that the modern reader would have trouble with, and it situates the letters in their historical context with 13 excellent, succinct section introductions to various series of correspondence. In 1988, the University of North Carolina Press did us all a favor and published a complete, one-volume paperbound edition of the letters. The letters themselves trace all extant correspondence between Thomas Jefferson and both John and Abigail Adams beginning in 1777, the year after both men worked on the drafting committee for the Declaration of Independence, up until 1826, when both men died, within five hours of each other, on July 4, on the 50-year anniversary of the document in which they both pledged "[their] lives, [their] fortunes, and [their] sacred honor." From the very beginning, these letters give us a view of America's founding by two of the people who had the most to do with it. Letters between Jefferson and Abigail Adams (along with John) begin after the Jeffersons and the Adamses served together as America's minister to France in 1784. In 1800, Adams and Jefferson were on opposite sides of one of the most contentious presidential elections in American history. Adams, a Federalist, stood for strong military preparation, a powerful federal judiciary, and an effectively pro-British foreign policy (though it was Adams, against the wishes of his own party, who secured peace with France in 1800). Jefferson, the leader of the emerging Republican Party (no relation), stood for stronger ties with France, a weak judiciary, and the abolition of standing armies and navies. The two sides savaged each other, and each other's standard-bearers, and Jefferson and Adams stopped communicating with each other. From 1796 through 1812, all we get are a few very formal letters between the two of them around the time that Jefferson was moving into Adams' house (The White House). And then, in 1812, something remarkable happened. Through the agency of friends, Jefferson and Adams began corresponding again. And, over the next 13 years, they exchanged almost 60 letters about the past, the present, religion, politics, books, France, England, slavery, Native American culture, and, well, everything else. This is one of the most remarkable stories of reconciliation in our history and proof that severe political differences do not have to be an absolute bar to respect, civility, and friendship. There are so many people talking and writing about history these days. But history itself has never been as available and accessible as these letters make the early days of America. Instead of reading other people's books about the Founding Fathers (including mine), take the time to read what they actually had to say for themselves. Really. You won't be sorry. Michael Austin, author That's Not What They Meant!: Reclaiming the Founding Fathers from America's Right Wing |

Review # 2 was written on 2009-06-03 00:00:00 A. P. Lilley A. P. LilleyWhen I started this book, I assumed I would slog through it, and learn some useful things, and get some enjoyment out of reading these Founding Fathers' own words instead of those of historians. I did not expect it would return to my bookshelf as one of the most beloved books there. The letters delve deep into the expected ' the inner workings of a young democracy, the establishment of a fledgling economic power on the world scene. And yes, there are points of mundane bureaucracy, passages about whale oil, salt fish, loans, insurance. Especially in the early years, much of John Adams' and Jefferson's correspondence was taken up with matters of business. Yet even within these passages, there are delightful gems, and in Jefferson and Abigail Adams' correspondence, there are far more abundant examples of the mutual friendship and admiration between the Adamses and Jefferson. Their personalities emerge, in a different and generally richer way than they do in even the best history books. As expected, Jefferson's prose stands out. Were there nothing else of value in the collection, it would be worth a read just to see him pepper even the most mundane topics with bits like calling an ambassador a "torpid uninformed machine," much less the longer passages that show his eloquence was not limited to important documents. But while Adams doesn't achieve the same frequent elegance, his letters are filled with reminders that he was an excellent statesman, and right more often than history gave him credit for (although Jefferson does in later letters). And then there is a lull in the correspondence, where the history books and the useful, concise chapter introductions of this book must fill in the blanks. The Adamses and Jefferson return to the United States. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson become political rivals, candidates in one of the most bitter election campaigns this country has known, leaders for a generation that agreed on independence, but not what to do after independence was won. For all the highlighter-worthy lines before this point, the greatness comes when John Adams sends a letter and a package after both are retired, initiating a torrent of letters that lasted until the two men died. Their topics range from education to metaphysics to aristocracy, but Adams' and Jefferson's late-in-life correspondence is far more a story about a seemingly impossible reconciliation. Somehow, both men found the capacity to either forgive, or forget, and a willingness to listen. "You and I ought not to die, before We have explained ourselves to each other," Adams writes. And they do, tiptoeing sometimes, and always explaining, not attempting to convince. The politics and the history are there in abundance, but to me, this collection of letters is more about a human drama where the cast of characters are some of the most important names in American history. I've read at least one historian that presented the letters as Adams and Jefferson posing for posterity. They were surely aware that these letters might be published someday, but posing for posterity doesn't account for the clear joy both express in having one great mind to converse with, one friend left from the generation of 1776. Scribbling out these letters with aging hands, they long for an hour of conversation, difficult to imagine in our age of cell phones and jet travel. These letters combine to tell a story about life, but also a story of death. In later years, facing their own mortality, Adams and Jefferson are unafraid of the topic. Religion, the afterlife, the rights of the next generation to take over. By the time I reached the final letters, the impossible timing of their deaths started to seem less impossible, and I found myself glad that neither had to deal with the loss of his dear correspondent. Not surprisingly, Jefferson sums it up better than I have managed to in this review: "A letter from you calls up recollections very dear to my mind. It carries me back to the times when, beset with difficulties and dangers, we were fellow laborers in the same cause, struggling for what is most valuable to man, his right of self-government. Laboring always at the same oar, with some wave ever ahead threatening to overwhelm us and yet passing harmless under our bark we knew not how, we rode through the storm with heart and hand, and made a happy port." |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!