|

|

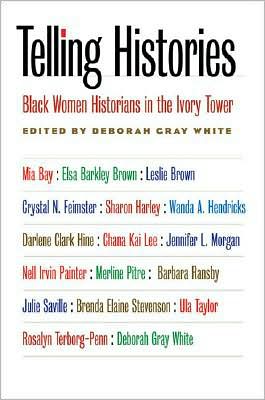

The average rating for Telling Histories: Black Women Historians in the Ivory Tower based on 2 reviews is 4.5 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2013-12-22 00:00:00 Erom Fonz Erom FonzTelling Histories: Black Women Historians in the Ivory Tower, edited by Deborah Gray White is a fascinating look at the history of the evolving state of race and gender relations within the United States. The seventeen autobiographical essays included in the volume, provide an intimate and insightful vision of our society's struggle with these complex and dividing issues, as viewed from the unique perspective of a distinguished group determined, intelligent, and articulate Black female historians. They are all well respected scholars who have made significant contributions to the historiographical record in the genre of African-American studies and more specifically within the sub-genre of African-American Women's studies. Their stories tell of the long uphill march, which all people of color in this country and Black women in particular, have had to climb in order to overcome the stigma of negative stereotypes ingrained in the societal conscientious of America. They each give the reader a strong sense of the feeling, which each of them felt so often in their lives, that they had to not only prove not only the validity of the work, but also their own personal validity as a Black woman, who refused to be held down or back by what society thought was their proper place. Doctor Deborah Gray White introduces the book in concise and lucid terms, describing the accepted logic of the Black community during much of the twentieth century and before. How African-American women were, "socialized from infancy to uplift themselves and their communities at the same time" through education.1 Doctor White asserts this was particularly so for those blessed with the advanced intelligence and opportunities to pursue their education beyond the secondary level and into college. These individuals she says were generally expected to return to the Black community and serve as both role models and mentors by taking up positions as teachers, social workers and nurses for example, thus uplifting their communities from within. But as Doctor Gray White points out, this was a false perception, which had been dictated by societal prescribed norms deeply seated in the ignorance and prejudices of the past. Citing the early twentieth century work of Gertrude Mossell and Marion Cuthbert's work a generation later, White shows that Black women had been earning a living for themselves and their families in a variety of other venues beyond those perceived limits of opportunity, by virtue of their literary, artistic and other talents, throughout the previous century. Thus she sets the tone for the series of seventeen well conceived and passionately written autobiographical essays, by some of the most well-respected names within the genre of African-American Women's History. This is truly a very special group of profound thinkers, whose efforts have given voice to generations of Black women and the extremely important contributions they have made to the tapestry of African-American society and in a greater sense to society as a whole. They include the pioneers of the Black Women's History realm such as Nell Irvin Painter, Darlene Clark Hine, and Merline Pitre, all of whom first encountered the ivory tower of American academia amid the turbulence of social upheaval of the sixties. The book's essays are presented in the order that each of these learned and articulate women completed their doctoral dissertations, many of which have gone on to achieve great acclaim within the academy and the literary press as well. Several of their books like Ar'n't I a Woman?, In the Struggle Against Jim Crowe, and Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol are now revered secondary sources and required reading for aspiring undergrads and graduate level historians as well. The remaining baker's dozen of contributors aside from those aforementioned and the editor, Dr. White, include in order the following; Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, Sharon Haley, Julie Saville, Wanda A. Hendricks, Brenda Elaine Stevenson, Ula Taylor, Mia Bay, Chana Kai Lee, Elsa Barkley Brown, Jennifer L. Morgan, Barbara Ransby, Leslie Brown, and Crystal N Feimster. These very telling essays convey almost chapter and verse the same systematic up hill battle these determined women have been forced to fight in order gain the prominence and respect they have earned both within the academic community and within society at large. Their careers stand as a powerful living testimony of indomitable determination to succeed and thrive with personal dignity while empowering themselves to move forward, which these powerful writers have shown the world has been the previously unnoticed legacy of African-American women. More importantly perhaps the inspiration which the youngest of this group have drawn from their elder peers is clearly being passed as well on to subsequent generations of scholars, and not just African-Americans or even women for that matter. For nearly every aspiring historian dreams of giving voice to those, whose stories have remained untold, to let the world know of the sacrifices and wisdom previous generations have to offer to the world of today and tomorrow. In that category of endeavor, this group of scholarly authors has indeed excelled, providing subsequent generations with a wealth of inspiration. These were women who refused to be neatly pigeon-holed into the old stereotypes which society sought to impose upon them and dared to carve their own paths. Their successes encouraged successive generations to also dare to assert their own right of presence in the hallowed halls of America's finest institutions of higher learning and the value of their scholarly endeavors. Strong, learned, and articulate women, whose research and writing has opened new schools of inquiry into the world of Black women in America's past. Far from being merely subjugated pawns of a system of racial and gender inequity, these historians have illuminated through their research and writing, the diverse and dynamic ways in which Black women have coped, resisted, and overcame the enormous injustices which have been visited upon their company. They have tackled head-on, such sensitive topics as the prevalence of rape and sexual exploitation of enslaved African-American women, in vivid and frank language and fully demonstrated not only the immediate effects of such acts on a slave community. but also the lasting cultural effects as well. They have delved as well into lynchings, the fight to achieve enfranchisement, and the intense struggle to survive against the backdrop of institutionalized racism of the Jim Crowe era and later during the civil rights era. The book does well at presenting the overriding point that these women had to virtually throughout their careers carry a double albatross of burden represented both by their race and their gender in a world, so thoroughly dominated still by a societal conscientious which overwhelmingly favors the white majority and men specifically. It also reveals the close network of ties which has developed between these ladies as they have strove to carve and flesh out the genre of African-American Women's Studies. This came most assuredly from the unique shared experiences which only Black women can fully comprehend. Every individual is both a product of and a part of the environment and circumstances of their own personal history. Much like it takes a recovering alcoholic or junkie to fully emphasize and understand what someone going through the DT's or the horrors of opiate withdrawal, there was no one else within the academy whom these ladies could fully and completely relate. As Stephanie Y. Evans so accurately and much more succinctly commented, in her 2008 review of the book, things like "hair texture or skin color" are not things which persons not having an ingrained understanding, which can only come from being African-American and growing up in that community.2 Perhaps Lois Rita Helmbold summed up what's best about this book, when she wrote in 2009, "The Black women historians in Telling Histories, tell it like it is, including their struggles to get advanced degrees and the ongoing disrespect they face in their jobs and toward their scholarship."3 This was the overriding essence of the volume as a whole and each successive essay reinforced and accentuated this theme extremely well. This is a book as well which was certain to raise hackles of the worst in society as can be seen in far too many public comments. Persons whose beliefs are fueled by the negativism and evil of racism and bigotry which has so long been steeped into much of our society. Passed along from generation to generation, despite the overwhelming evidence of its illegitimacy by any manner of scientific proof, such vile beliefs sadly do remain a part of many even today. That these scholars, who also all happen to be black women, have accomplished so much and come to be viewed with such tremendous respect by all of the peers, regardless of gender or race, gives testimony to the credence and validity of their collective work in the field of black women's history. That they have indeed been victims at times of prejudice because of their race and or their gender is absolutely a given. The truth is even today, well past a decade into the twenty-first century and long after terms such "political correct" and "ethnic diversity" have become a part of our everyday language and watch words in all matters of the public realm, prejudice based solely upon learned social constructs of race, gender, religion, and others exists in America. While some might not agree, it can be seen in persons of every creed and color in this country and elsewhere. No one race, nor gender, nor religion even, can claim that none among its particular membership harbors such negative feelings towards those who are somehow different than themselves. One need only cast an eye beyond our borders to see that such idiocies exist elsewhere in the world as well. In many parts of the world girls are routinely forced to undergo mutilation of their bodies in the name of preserving their purity or is it religious purity, not that the reasoning behind such atrocities holds any merit, nor negates their horrors. There remains today a flourishing international trade in human flesh which traffics mostly in young women and girls, but also in boys as well that feeds a world wide market fueled by erotic sexual appetites of others. The world is simply not always a nice place. It is as true today as in any other era of history, but this book and the stories it contains gives breath to hope at least that this can change. The courage these women have displayed in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles and circumstances proves that where there is education which allows the truth to be revealed it opens eyes and opens doors, through which determination and perseverance may invade and prevail. Such events can only advance the human race and bring it together, for where there is enlightenment, there is understanding and this is the crucial element in finding the commonalities which all of humanity shares. Which makes this volume destined to become an intrinsic feature of the historiography of African-American and gender studies as well as a classic study of the evolution of the field of history in general. |

Review # 2 was written on 2018-04-14 00:00:00 Jason Sperry Jason Sperryupdate:4/2018 recommend documentary: Living Thinkers: An Autobiography of Black Women in the Ivory Tower by Roxana Walker-Canton (2013) good luck |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!