|

|

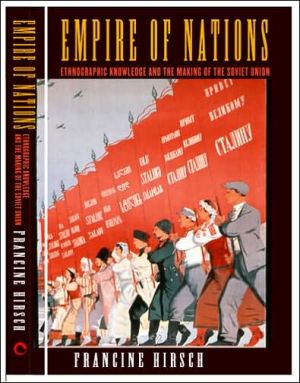

The average rating for Empire of Nations: Ethnographic Knowledge and the Making of the Soviet Union based on 2 reviews is 3 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2021-03-02 00:00:00 Jung Jin Hyuk Jung Jung Jin Hyuk JungFrancine Hirsch's "Empire of Nations: Ethnographic Knowledge and the Making of the Soviet Union" is one of several post-Cold War works that specifically challenge Conquest's ahistorical and baseless accusations against the USSR. Ethnographic knowledge had a profound influence on the USSR. Beginning with Lenin's alliance with imperial-era ethnographers, such as Sergey Oldenburg, the Soviets invested considerable time and resources in understanding the USSR's numerous peoples. Ethnographic knowledge was incorporated into virtually all aspects of the USSR: the creation of national republics and oblasts, collectivization and industrialization, the fight against Nazism, etc. What really interested me in this book was reading about how Soviet ethnographers struggled against the biological determinism of their German, British, and American counterparts. Nazi "racial science", Hirsch writes, was an ideological threat against the Marxist-Leninist theory that different ethnohistorical groups corresponded to the different stages of socioeconomic development. Teams of Soviet ethnographers, anthropologists, doctors, etc. were dispatched across the USSR to counter this threat. Soviet leaders, including Stalin, wanted empirical evidence that the so-called "backwardness" of some peoples was not due to "biology" but to due to Tyloresque "cultural survivals". Hirsch, like Adeeb Khalid, Terry Martin, Adrienne Lynn, and Arne Haugen, and others, is a must read for those interested in nationalities policy in the USSR. |

Review # 2 was written on 2012-04-07 00:00:00 Peter Moak Pyp Exp Peter Moak Pyp ExpThe epigraph of this book is a description by Hanna Arendt of history as a man-made process, and this is exactly the aspect of Soviet history that Hirsch explores. Her research is guided by the attempt to discern how Soviet rule managed to create nation-states and change the group and individual identities of the Soviet people. She is also interested in the ways in which European ideas about "empire" and "nation" became adapted in the Soviet-Marxist context. Previous literature on non-Russian nationalities victimized them and failed to integrate them into the Soviet "master narrative," contributing to the conflation of "Russian" and "Soviet." Hirsch moves beyond the totalitarian and revisionist models that debate the degree of the Soviet state's control over its population. Instead, she argues that the regime mobilized the population in such a way that even its resistance to the Soviet power ended up strengthening it. Hirsch challenges the conventional periodization of Soviet history. She begins her narrative not in 1917, but with the 1905 revolution, which made obvious to both the Bolsheviks and the imperial experts the power of non-Russian nationalism in the Russian Empire. Both Bolsheviks and experts were influenced by concurrent European debates and believed that this phenomenon was due to Russian oppression and needed to be counteracted by using scientific methods. The First World War belatedly brought the ideas of these experts to the attention of the Russian government because non-Russian population needed to be mobilized, used as a productive force, and its separatism countered. When Bolsheviks came to power in 1917, they were faced with the major task of overcoming "historical diversity" of the former Russian Empire, which despite their anti-imperialism they wanted to preserve in order to maintain access to its resources. In these tasks they were allied with the imperial experts, whose services they engaged. The understanding of Bolshevik ideology is crucial to explaining their nationality policy. They believed that national development (superstructure) followed economic development (base), and that under socialism all nations would merge into one. In order to act on both the base and the superstructure, Bolsheviks and the imperial experts together formulated the approach that Hirsch calls "state-sponsored evolutionism," a combination of European anthropological theories and Marxist conceptions, that aimed to speed up peoples' development. Throughout their rule, Bolsheviks held nationalities to be both primordial and constructed. Thus, historically originated groups that were victims of Soviet modernization could be acted upon by the state in order to reach the Bolshevik's ultimate goal: amalgamation of nations under communism. This would be done through "double assimilation" of the population into nationality categories and nationality categories into the Soviet society. Soviet Union defined itself as the sum of its parts, unlike tsarist Russia or European colonial powers, which viewed themselves in opposition to their colonies. Contrary to Pipes, Hirsch shows that in 1924 the formation of the Soviet Union was only beginning, and it was a fascinating "work in progress." Soviet government engaged imperial ethnographers and local elites in the interactive process of the shaping of the Soviet Union, using the data they supplied in accordance with their own objectives to shape the eventual structure of the Soviet state and develop the peoples' national identities. The creation of the Soviet territorial-administrative structure was not a whimsical policy, or a policy of "divide and rule," as argued by scholars like Caroe. On the contrary, the attempt to compromise between economic expediency and national idea shaped the eventual (very complicated) structure of the Soviet Union. Census, map, and museum are the "cultural technologies of rule" that Hirsch explores in the section of her book dedicated to the 1924-1934 period of "sovietization." The census, for example, was used not only to count representatives of a certain nationality, but also to inform people about the nationality which they represented. Soviet population understood that identification with a certain nationality could lead to benefits, and thus by the early 1930s nationality became a fundamental marker of identity among Soviet peoples. A fascinating example is the Tajik SSR, which was carved out from the Uzbek SSR on the basis of census data. By late 1920s, the Soviet state began to establish tight control over experts and local elites (campaign against the Academy of Sciences), but continued to rely on the information they provided. Stalin's "great break" (1928) called for a faster building of socialism, and to further this, "smaller" and "less developed" nationalities were amalgamated into larger groups. This was not a "retreat" from earlier Soviet nationality policy, but an attempt to accelerate it. Strengthening of Nazi political and scientific forces that began in 1930 presented both a geopolitical and an ideological threat to the Soviet Union. Nazi scientists' belief in the danger of inter-ethnic mixing was detrimental to the Soviet hope of the eventual unification of all nations under socialism. This development caused a push to further accelerate state-sponsored evolutionism. In order to prove that it was nurture, and not nature that explained the relatively slow national development of several of the Soviet Unions' "backward" nations, Soviet ethnographers came up with the idea of "survivals of the past" (perezhitki proshlogo), such as shamans, which were holding these nations back. Soviet scholars of race continued with minor exceptions to define it in "neutral" (socio-historical, and not socio-biological) terms. In mid-1930s, national oppression within USSR was "abolished," and Russians were therefore no longer great power chauvinists. The promotion of Russian national culture that followed was not, according to Hirsch and counter to Brandenberger and Martin, a retreat from the Stalin revolution, but the celebration of the Russian proletariat's "progressive historical role," and not of the Russian imperial past or the Russians' innate traits. By the late 1930s, the threat from Germany became geopolitical. The Nazis justified their expansionism by claims to protect Germans abroad, which made the Soviet state concerned about its diaspora nationalities. Their loyalties were to non-Soviet states, and they could therefore never merge into the Soviet people. NKVD deported these nationalities from border regions. Ethnographers provided NKVD with the scientific basis for the soviet vs. foreign nationality distinction, this continuing to play an active role in the process of subordinating Soviet people to the Soviet power even when they were persecuted. As a result of the Nazi threat, Soviet nationality policy became increasingly contradictory: while touting national self-definition, it forbade Soviet citizens to choose which nationality they were ascribed to on their passport. This policy did not, however, indicate a shift to Nazi-like biological view of nationality. Non-Soviet diaspora nationals were not considered degenerate, but they would not be able to join the amalgamated Soviet people. A fascinating example of Stalin's involvement is the effect of his declaration that around sixty nationalities inhabit the Soviet Union. Stalin left it to the ethnographers to cut their existing list of nationalities down to sixty. In the epilogue, Hirsch rushes through the remaining decades of Soviet history. Marr's theory of national development as following economic development remains prominent after the war, but the projected merging of nationalities into the Soviet people, although bound to happen, is constantly postponed. Post-war ethnographers tout the benefits of Russian language use as a means to improve of international communication, and define the eventual Soviet people as a combination of all Soviet nations' national traits. However, local elites are much more interested in the benefits that their national status grants them today, than in a unification and possible linguistic russification tomorrow. Soviet Union remained a work in progress: after the thaw, and especially during perestroika, nations would be returned to the census list of nationalities. Nationality, the main a source of recognition under the Soviet Union, eventually became the most important official category for Soviet citizens. Unlike Suny, Hirsch believes that economic difficulties, loss of faith, and overextension contributed more to the Soviet collapse than nationalism, but the latter does explain the way in which this collapse happened, since all official soviet nationalities already had institutions, cultures, languages, elites, and a developed sense of national consciousness. Soviet Union's high level of economic integration, ethnically diverse population of the post-Soviet states, and the problem of creating a usable past for these new entities ensure that de-sovietization will be a work in progress for years to come. As Hirsch repeatedly points out in her footnotes, she argues against several of assertions that Martin makes in his work. First, she does not agree with his use of the term "affirmative action," which Martin disconnects from its very specific historical context, but also fails to accurately describe Soviet nationality policy. The goal of the latter was not to promote national minorities at the expense of the Russian majority (after all, Russian were not forced to give up their language and remained the dominant nationality in non-national Soviet territories), but to speed both groups through the stages of national development. Hirsch also seems to disagree with Slezkine and Barber, who emphasize the discontinuity between imperial elites and the new generation of Soviet historians. Instead, Hirsch claims that under pressure from above ethnographers sovietized their discipline themselves. Comments/Critique: At the outset, Hirsch asks the question: "Why did the USSR fall apart along national lines and how has it endured for so long," which is closely related to her argument, but it not quite answered by it. The claim that factors other than nationalism were decisive in the collapse of the Soviet Union, which she makes in the epilogue, really needs much more support, and does not directly flow from her findings. If the Soviet power was, indeed, interactive, and thus strengthened even through resistance, why did it collapse in 1991? Hirsch describes the effect that Stalin's declaration of the existence in Soviet Union of sixty nationalities had on ethnography. I wish she would have also speculated why exactly Stalin made this declaration. I understand that the decreasing number of nationalities meant the success of the revolution, but why sixty, and why at that specific time? |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!