|

|

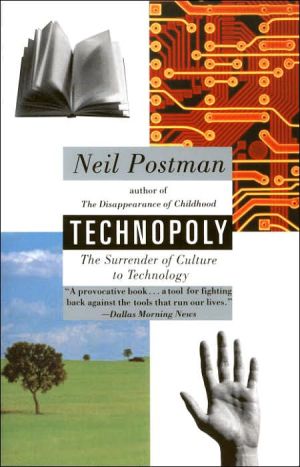

The average rating for Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology based on 2 reviews is 3.5 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2010-07-19 00:00:00 Chris Callen Chris CallenA large part of this is just stating what I would take to be pretty much the obvious. No 'new technology' is ever fully positive or fully negative. I can't remember where I heard recently that an environment that has rabbits added to it is not, say, the Australian bush with rabbits, but actually a new environment. Technology does much the same thing with the human environment. The 1950s were not really just the 1940s with television added and the 2000s weren't just the 1980s with the internet - new technologies create a new environment and that new environment has both benefits and disadvantages when compared with what came before. Except, of course, we live in a world where we don't like to talk about the disadvantages. Technology, in Mr Postman's opinion, leads to Technopoly and Technopoly is a kind of society that is obsessed with the benefits of technology to the point where everything needs to be measure and assessed on the basis of how 'efficient' it is. This is a book that challenges this cult of efficiency and that looks at some of the disadvantages technologies (particularly computer technologies) have brought to our world. This book was written in the early 1990s, i.e. well before the internet as we know it now. As you know, there have been quite a few books in the meanwhile talking about the negative impacts of the internet - particularly on quality journalism (if that is not an oxymoron). It wouldn't be fair to call Postman a Luddite - his criticism is both careful and intelligent. He points out that we have become obsessed with the scientific method - a method that we think is about measuring everything and about coming up with strict laws that the world is to conform to and that this is the aim of the 'social sciences' as well. There is a lovely part where he says that the nineteenth century created images of people that were presented to us by novelists, so Dickens might create a Uriah Heep and we might then use this character as a basis for categorising or understanding a certain type of person. Today we would be much less likely to do that, today we tend to base out character types on the work of social scientists, such as Freud, Erik Erikson, Marx and so on. This is an interesting change and an interesting observation. Postman says science is only properly applicable to processes, but the proper sphere for social 'sciences' is 'practices'. The difference being that processes (such as water boiling) are measurable and conform to universal laws that are discoverable and describable. Practices, such as drinking tea (as strange as this may sound) are not universal and actually depend on a particular culture. When the tools of science are applied to practices, rather than processes, it is remarkable how often we are left with banalities masquerading as profundities. Postman quotes a study that found that most humans are afraid of death… I guess scientists may one day even have the technology to be able to prove that people like food and quite enjoy sex. He makes the interesting point that we are a society obsessed with information, but that we have lost an overarching belief system that would allow us to filter that information and thereby make sense of it. Let me give you a case in point. The other night I received an email from someone I love very much that said that next month Mars would be closer to the Earth than it had for thousands of years and that it would appear to be about the size of the full moon in the night sky. It turns out that this is one of those bizarre hoaxes (I've never quite understood the joy people must get from spreading this stuff) - but Postman's point is that we are so swamped today with useless and effectively meaningless information that we have become quite credulous. And why shouldn't we be? We are confronted with an enormous ocean of information and most of it bombards us piecemeal as unconnected factoids. There was a time when religion provided the overarching framework to judge the worth of information - but religion has lost its ability to play that role. However, we do need a way to separate the meal from the dross. Interestingly, he says that one of the few ways left in the US is the legal system. Courts have rules around what constitutes evidence and president and as such courts are one of the few remaining 'arbiters of truth' left in society - which Postman uses as a possible explanation for Americans' tendency to be quite so litigious. He ends his book by talking about how to fix things. I tend to agree with him, but I can also see that many people would find this quite an unsatisfying part of the book. He points out that we should become loving freedom-fighters. This is from a part of the book that ought to make Americans feel very proud. It explains how the US has stood as an example to the rest of the world in its ongoing experiment in democracy. He also talks of the need to change the way we teach children - first that they need to become aware of the fact that what is worthwhile requires effort and second that they need to understand subjects have a history. In fact, he reiterates Marx's view that all subjects are essentially history. That it is impossible to understand electricity without understanding the history of the concept, you know, from Maxwell on. I think this is wonderful advice - it does seem to be something the publishing world has jumped on recently, with lots of books published about say the potato or nutmeg or the number zero and the impact these have had through time. There are nice things in this book about technologies and many things I didn't know. I knew it was a huge innovation that zero was introduced into our numbering system, and that our placement system of numerals (0-9) made things infinitely easier for mathematics than Roman numerals. Imagine multiplying MCVI by CLXVII - except, as Postman points out, no one ever really did. Roman numerals were for writing numbers, not really for manipulation - arithmetic manipulation was done on counting machines like abacuses. There is probably a little too much reliance on Popper's views of science theory in the book - it is hard to imagine, but Popper's theory of refutation isn't the only theory in the history of the philosophy of science. Nevertheless, he does make a strong case for why science is really about limiting imagination and reducing, as much as possible, the number of hypothesises in any given subject. He gets this idea from The Ascent of Man. This is not meant as a criticism of science, but rather as a statement of nearly banal fact. I think the main idea to take away from this book, though, is that despite our obsession with information it is probably not the case that what we need to fix any of the real problems facing us today is more information. Global poverty, for example, will not be solved by more information, nor will war or global warming. He makes the impressive rhetorical point that if computers had been invented before the atom bomb was developed that people would have said that we could not have invented the atom bomb without the computer. The fact that we did invent it without the computer does seem remarkable - and the fact it does seem remarkable says much about the culture we live in. And the last thing I want to refer to before ending this review is that he has a very interesting take on the Milgram Experiment (the one where people administer electric shocks to people they cannot see up to the point where the people they cannot see appear to die, the test of authority and empathy). He points out that it is hard to know what this experiment really tells us. His view is that it tells us what people do in the very bizarre and unnatural setting of a psychology lab - and tells us remarkably little about what people are like in the real world. As he points out, how would we fit the Danes into this experiment, the ones who risked their lives to save Jews from Nazi death camps? Should we say the Danes contradicted Milgram's experiment? Although I still find the Milgram Experiments deeply troubling, I do think he has a point that studying people in highly artificial environments should give us pause before accepting uncritically the conclusions from such studies. Postman's books are always thought-provoking - I enjoyed this one very much. |

Review # 2 was written on 2012-04-22 00:00:00 John Hough John HoughThough Postman wrote this book in 1992, his ideas remain as relevant as ever in 2012. If he thought Technopoly was running rampant in '92, I can't imagine (well, I can) his disgust at technology's further rise to eminence in the past twenty years. If you're one who recognizes that facebook, iPhones, and Twitter actually have downsides, then you'll be intrigued by Postman's passionate arguments, ones that extend beyond electronic technology because, after all, the computer was in its infancy then. Rather than choose a specific star rating, I'll allow my previous sentence to serve as my recommendation. The mere act of assigning the pleasure or thought-provoking-ness of the book a numerical, measurable value would feed into Technopoly's invisible technologies whose sole purpose is efficiency. By 'invisible technologies', Postman refers to the processes that occur under the radar, byproducts of "progress" that go largely unnoticed by the average person. How this would then play out: By me giving the book a 3-star rating, I show that I buy into the belief that a reading experience can be quantified, the subsequent statistic therefore being much more easily managed/manipulated/analyzed to produce some kind of 'truth' about the quality of the book than a lengthy review. Postman applies this to education, science, pop culture...all with entertaining criticism. At the beginning of the book, Postman informs his reader that he recognizes the benefits of technology, and the reader must keep that in mind because the majority of the book is Postman examining and bringing to light the effects of technology that we overlook, the negative effects. If you forget that his goal is to reveal technology's underbelly, you'd wrongly assume that Postman is against any technological advance. He raises questions that I find especially relevant as a budding educator, questions that nevertheless pertain to anyone who chooses to think critically. Postman's overarching question (the same question he asks in The End of Education) is, What narrative can unify a people and give them purpose? Damn. What a question. So how then will I live in the Technopoly of America? While I don't feel the need to abandon facebook (or my goodreads account), I'll need to continue questioning what I gain and lose through the use of those technologies and look upon the gods of efficiency, convenience, and 'progress' with a critical eye. I can enjoy some of the easy things, like a star rating system for books or movies or music, so long as I make sure to pursue the more enriching and subjective conversations about them, face-to-face, in the same room with friends. I'm up for the challenge. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!