|

|

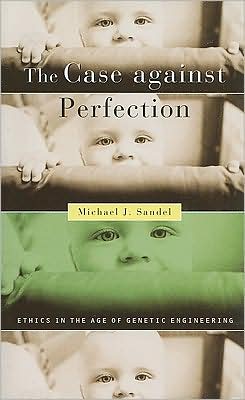

The average rating for The Case against Perfection: Ethics in the Age of Genetic Engineering based on 2 reviews is 3 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2020-07-21 00:00:00 Abdul Bari Abdul BariBased on what I've read and seen, Sandel sounds like the kind of philosophy teacher that students would be privileged to study under. And he may even be a kind and generous man. But he is also a social reactionary with some horrible views. Sandel believes that life's imperfections are a "gift" from God or Nature. He thinks that Humankind should not play God/Nature, since this would encourage a false attitude towards reality, namely that of hubristic mastery. Sadly, the fundamental arguments of The Case Against Perfection are largely badly argued and morally reactionary. The whole argument of this book rests on a straw man. "Perfection" is not the goal of most human enhancement advocates. The goal of human enhancement, whether in health, work life, leisure, relationships, sports, or social life, is to make things better for people. But this enterprise, according to Sandel, threatens the integrity of humanity. As it happens, evolution has not made us as functional, healthy, or happy as we would like to be. The "normal" state of human beings has "gifted" people (to use Sandel's own terminology) with various intractable problems. Instead of going about trying to solve our remaining problems, Sandel would prefer for people to embrace those problems - "imperfections" - and learn to live with them. This attitude might be justifiable if the status quo was acceptable or if the remedies were worse than the disease. Neither is the case. The status quo is a horrible state of affairs. God/Nature has made us barely functional. We human beings have managed to make our lives a little better with various"hubristic" interventions such as technology, science, political institutions, and sustainable economic development. And by and large the remedies have been much better than the underlying disease. The same trend is likely to continue and the human enhancement project must go on. The promise of ever new technologies and enhancement tools to improve our lives - whether through drugs, gene modification, gadgets, or A.I. helpers - is the saving grace of our sorry human condition and something to celebrate. So, Sandel's position is a reactionary defence of the status quo. In effect, it is a justification for misery and hardship in the name of "virtues" and "sacredness" and religious sensibility. Of course, a philosophy book can be good in its methods if not its conclusions or premises. However, the book does not redeem itself on the structural level either. It relies on an unimpressive combination of intuitive reasoning, rhetorical persuasion, and a series of entertaining anecdotes. There are flashes of brilliance where you get the sense that Sandel can be a good and generous philosopher. Sadly, most of the book is a poorly argued straw man argument in defence of a horrible status quo. |

Review # 2 was written on 2015-11-27 00:00:00 Lori Meehan Lori MeehanThis book was recommended to me from a friend here on good reads. And it was nice as he said - look, it's short and interesting, but I can understand if you don't have time etc. and that nearly convinced me to read it straight off. But it is sort of off-topic at the moment - I know it might not look like it, but this is me being quiet on good reads, as I'm trying to write up my thesis and so shouldn't, I mean I really, really shouldn't, be doing this or anything else. Mmm. Anyway, I have this real problem with the whole idea of genetic manipulation, selection and perfectibility. Part of that problem is that I have an older sister who is intellectually disabled, and although that wasn't exactly caused by her genes, I'm still particularly sensitive to the kinds of simpleminded 'solutions' (final solutions, even) that get trotted out to 'the problem with people with disabilities'. But that is only a wee bit of my problem. It isn't at all clear just what the 'perfect' human might look like. There is an image going about the internet of what Jesus would have looked like - it doesn't pretend to be actually what he looked like, but a kind of average face of people born around Galilee at or about the time Jesus was. The image certainly doesn't look like the lanky white guy that the Son of Man is generally painted as. The bit that really attracted my attention, though, was that he was probably only about five-foot-one. That is, Jesus was someone that would easily have qualified for some of the growth hormone treatments discussed in this book. The other problem I have with genetic improvements is that genes are very deeply associated with the founding myths of our culture - particularly the idea that we live in a meritocracy. It is interesting that some of the arguments put forward in this book, which I enjoyed, by the way, I thought it did a really good job in putting forward issues from many sides and really trying to find a way through the thickets and brambles, but that the arguments here about why perfectibility is wrong were based on our revulsion when we feel meritocracy is being overthrown by a kind of cheating. And the use of such gene 'perfecting' of humans is seen as a kind of cheating. This review is going to be in two parts. The first part is going to be the standard McCandless attack on the idea of merit. The second is my argument against perfecting humans as being part of my understanding of Darwin and his little theory of natural selection. Right, merit. God, I really have learnt to hate that word over the last couple of years. The idea is that our society is essentially one that is based on merit. That is, if you are good enough there is enough leeway in the system to allow you to succeed. Hard work, great ideas, being the guy on the spot - or perhaps Bauman's lovely idea of 'pointillist time', where any of us could just as well be the next-big-thing - any dot on the landscape could suddenly explode and become an entire universe all on its own (our own) that no one had ever expected before. The only thing that is holding us back is merit. If you haven't succeeded it is almost certainly because you don't deserve to succeed. No need to take it personally - although, let's be honest, it is pretty well impossible not to take it personally, what could be more personal? - some people have it, and some people don't. And we don't, clearly. Pity, but that is the way it is. This is a remarkably effective story, this merit myth. Those who have all of the good things get to keep everything they have got, while those that don't get to learn from the myth of merit, so as to make them feel bad about themselves, rather than to feel ripped off. I saw this posted somewhere the other day - essentially that 100 people in the US own as much as the whole African American population of the country. The thing is that, in the US in particular, social mobility is remarkably low. Essentially, the country has a caste system. You are born into a caste and the chance of you moving out of that caste is virtually zero. But if the world is going to still be considered a meritocracy, then you really have to come up with something that will explain this lack of social mobility while still being able to blame those who fail for their own failure. And the solution forever and ever to this problem has been to play the gene card. This remarkably effective solution helps to explain away some of the harder to explain problems immediately. Why do the children of the poor remain poor? Bad genes. And the rich? Good genes. It is all manifest destiny right in front of you, hardly any need to ask the question even. And that is part of the problem with this whole idea of perfectibility - if there is a perfect human (whatever that could even mean) then the rich are more likely to be able to afford the technology that will provide them with those perfect genes as we get better and better at manipulating such things, and so we will be forever left behind - as if we weren't already. My problem with all this is that the arguments are a bit circular. There actually are no real measures for human worthiness. Smart people can be completely socially dysfunctional, cultured people can build concentration and extermination camps, people who like dogs can flick the channel when images of children dying come on the TV, and the list goes on. If we need to be perfected, the thing we ought to work on - the thing that gets to be on top of the list and a long way ahead of being able to run-about quickly on grass after a ball or to cram ever-longer lists of nonsense words into our heads, is empathy. We really could do with many more empathetic people kicking about the place - it might not help, but I can't see how it could hurt. Empathy doesn't really come from genes, at least, I certainly hope not, but rather from practice. And it is formed from a fundamental believe that we are all 'the stupid guy'. I'm not a religious man, but if I was my favourite saying would be 'there but for the grace of God go I'. Like I said, we are all the stupid guy and if we aren't right now, we very soon will be. Our only hope is that people will be nice enough to us to forgive us our idiocies, because if anyone looks too closely, none of us passes the test. We are all, every one of us 'human - all too human.' The second part of all this is Darwin. You see, this book mentions Galton - Darwin's half-cousin and one of the early eugenicists. He decided Darwin was saying that since we can use artificial selection to make ever-faster racehorses, why can't we used the same principles to make ever-better humans? All we need do is encourage those with good genes to have more kids and, at more or less the same time, to sterilise those with bad genes and all will be well with the world. I think this is a fundamental misreading of Darwin - not just a wee bit wrong, but actually a complete misunderstanding of what Darwin was on about. The key to evolution through natural selection isn't the narrowing of the gene pool, but rather making sure you have genes that are suited to your environment. The problem is that the environment isn't really a fixed thing - it is, in fact, something that is always changing. One of the problems with many species is that they find themselves trapped in their own specialisation. The koala is a favourite example. Here in Australia the koala is often the most expensive animal to keep in a zoo. Sounds weird, but it is true. Why? Because koalas can only eat one kind of gum leaf and that only grows on one sort of tree (oddly enough) and that tree only grows in one area of Australia - so zoos not in that area need to bring these leaves constantly in from this one area and that quickly becomes expensive. The problem is that you don't really have an Australian zoo if you don't have a koala - but it always amuses me that it is often cheaper to keep a lion or elephant in an Australian zoo than a koala. And the koala problem isn't just a problem for zoos. If that particularly tree dies out, so does the whole koala population. We humans can't really laugh, much of our agriculture is based on super-phosphates, which we get from oil. So, like the koala, we also feed on a single product that has a limited life expectancy, given we will eventually reach peak-oil, presumably. We, too, have wandered down a particularly narrow and dangerous ecological cul-de-sac, only confused by the fact we keep calling ourselves 'omnivores', when we feast solely on oil. The point I'm trying to make is that any 'perfecting' of us as humans will invariably narrow our gene pool. We are, to quote that amusing meme, all seeking to be above average. By getting rid of the botched and bungled, we will be narrowing down our genetic variability and in doing so we will not be doing ourselves any favours. Diversity isn't just a nice 'kinda-leftish' idea, it is actually our only hope. Not because it 'teaches us compassion' - and if it does, that's a side benefit only. But because diversity is what allows for variation, adaptability and evolution, we are undermining our species if we keep seeking sameness. Accepting diversity is good for us all - and seeking perfection is a complete waste of time. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!