|

|

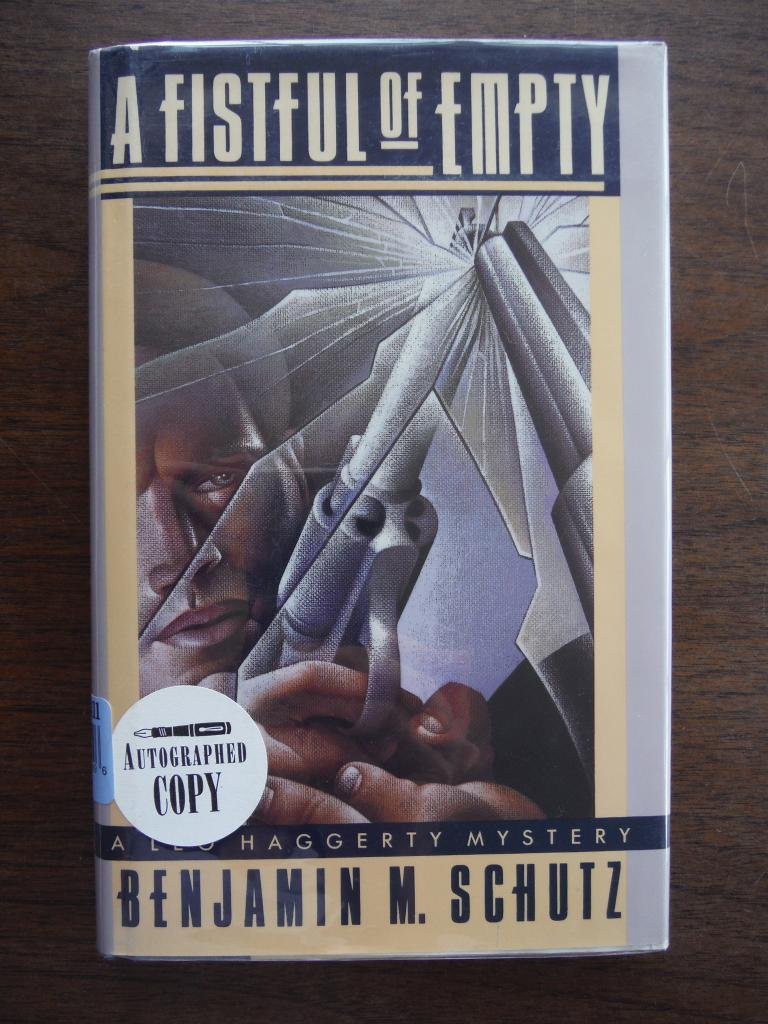

The average rating for A fistful of empty based on 2 reviews is 4 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2012-03-27 00:00:00 Mary Strawbridge Mary StrawbridgeI always feel the same way after I finish one of his books: "Man, that makes total sense, how could anyone reasonably disagree that inequality is skyrocketing/we need universal health care/China needs to revalue it's currency/the Republican Party is insane/free trade rules?" Even his detractors, like the Wall Street Journal editorial crew, or the legions of bloggers who exist only to find fault with his writing, readily admit that he's been immensely successful as a popularizer of economics and as a partisan for his own views. I like him not only because he shares my views as a liberal of the New Deal/Great Society school of thought, but because he has a way of illustrating complex debates in a way that's not only clear, but that seems to me as the way I would have looked at it all along, if only I could have put it into words, and he gives me a solid framework to say why. It's very cliche to compliment someone as "objective" because they "criticize both sides" (think of all that fawning praise for South Park back in the day) and take a pox-on-both-your-houses attitude towards big issues. I think that's dumb, not only because it assumes that there are only two sides to a debate, and that it's always somehow possible to take an average of each position and make sense (does it really make much sense to invade half of Iraq, or cut income taxes for people whose last names are A-M?), but because it rewards an unthinking "moderatism", where you don't really have to think about what people are saying, only that you want to somehow triangulate yourself and avoid doing any critical thinking. That's exactly what this book is about - criticizing both right-wing proponents of supply-side and Friedmanist monetary theories as well as left-wing proponents of strategic trade theory in a way that illustrates not only why you can't simply say "let's split the difference between these theories and call it a compromise", but also why it's vital to take the time to think clearly about what people are telling you and whether their numbers add up, and why you can't always trust people on your "side". Peddling Prosperity is very clearly a book aimed at a popular audience, both because most (but not all) numerical exercises are relegated to the appendix and because it's structured as a narrative, of the near-mortal wounds that Keynesian economics suffered in the 70s after its triumphs in the postwar era, the rise of potential conservative alternatives, and those alternatives' eventual failures and the (seeming) Keynesian resurgence in the early 90s. It was published in 1994, so it's a bit out of date, but it's actually very interesting to see echoes of the then-cutting edge worries about Japan and transpose them 15 years to the present-day, since most of the debates about government activism, the deficit, and international competitiveness haven't aged a day. Press releases and popular discussions of issues certainly haven't gotten any more sophisticated, so it's somehow still a breath of fresh air to read explanations of trade or productivity that are aimed at a wide audience without being dumbed-down to sound bites. Virtually every section, if you read closely, follows an A-B-C sort of script: someone is claiming A must be true, but here is data B, which actually implies C, so therefore they're wrong. This pattern shows up very frequently in his writing, and this book is no exception. Harsh, but always rigorous discussion of the history and reasoning behind various alternatives to Keynesian economics over the years are backed up by charts, graphs, and most importantly, the models behind these ideas. Part of the reason why stupid notions like endless tax cuts for rich people persist in the world, aside from the obvious self-interested aspect of wealthy donors and lobbyists, is because those notions are sold within a seemingly-plausible framework with a strong narrative: by cutting taxes for rich people, they will be able to create more jobs for people and more prosperity than if that wealth is given to other people; the more taxes you cut, the more jobs you create, and conversely, the more taxes you raise on these wealth-creators, the more jobs you destroy. By walking the reader through these implicit models, showing you the data, and giving you the reasons why they're wrong, Krugman both avoids simply throwing out ad-hominems (though there are some barbs in here) and gives you a way to think about future claims. One of the reasons why he has earned such a reputation as a strong liberal is due to his staunch opposition to the Bush tax cuts in 2001 and 2003; reading the math behind why the Reagan tax cuts failed (and, closer to home, why the recent late-2010 extension of the Bush cuts will fail utterly to bring prosperity), you become... not particularly optimistic, let's say, about people's ability to learn from their mistakes. The subtitle coins an excellent phrase which I am surprised has not gained wider currency: the Age of Diminished Expectations. While this book was written before the Clinton-era boom had really taken off, I remember growing up in the 90s and thinking of it as a time of seemingly permanent growth. Looking from today at the numbers, though - the steady decrease in productivity growth, the increasing inequality, the growing strength of the truly awful movement conservative wing of the Republican Party - I'm amazed at how satisfied people are with such mediocre growth when compared to the global trente glorieuses after the war. It would be easy to despair at the gradual lowering of the bar, but even during his discussion of massive failures, like the monetarist experiments in Thatcher-era Britain, the emphasis is on the math and logic behind why those policies failed, which prevents the book from sounding too depressing even if the conclusions behind it are plenty depressing. The ending section about the rise of the strategic traders in the Clinton administration is a model of analytical clarity - the presentation of subtle economic logic about how the budget of a national economy is not like that of a company's balance sheet and all the mischief that that fallacy immediately brings to mind Obama making exactly these mistakes with his Council on Competitiveness, chaired by the CEO of a company that has outsourced thousands of jobs and shuffled around billions in taxable income. So even though the endless recurrence of terrible economic ideas will not end anytime soon, the book offers invaluable perspective on their sources and how to evaluate them. The focus is always on the data, and while Krugman may not always be right (his dismissal of critics of Japan's trade surplus in the 90s sits oddly with his criticism of China's seemingly very similar trade surplus in the 00s, even given the vastly different economic circumstances), he gives you all the tools and ammunition you need to form a coherent counter-argument. |

Review # 2 was written on 2009-01-05 00:00:00 Michael Pinzine Michael PinzineKrugman's Peddling Prosperity is a lucid deconstruction of supply-side economics; a strident (and sensible, as far as I can tell) defense of Keynesian theory after its purported demolition by Milton Friedman in the 1970s; an acknowledgment of what conservative economists got right in the 1960s and 1970s; a case against the assertion that Ronald Reagan's economic policies were catastrophic, as opposed to merely harmful; a plea for economic policy to be better informed by actual economists as opposed to pop econ policy entrepreneurs, such as Robert Bartley, Arthur Laffer, and George Gilder on the Right, and Robert Reich and Ira Magaziner on the Left. Long-standing animosity between Reich and Krugman (see p. 254ff.) probably explains why as Reich's star rose in the Clinton administration and now again in Obama's, Krugman is not allowed at the grown-ups table. That Krugman's credentials have lately been burnished with a Nobel Prize and his economic prognostications, once mocked with knee-slapping derision by the Bush-fellating Right, have proven prescient, makes me wonder just how far President Obama's conciliatory, "team of rivals" approach really extends. ***** Favorite quotes: An Indian-born economist once explained his personal theory of reincarnation to his graduate economics class. "If you are a good economist, a virtuous economist," he said, "you are reborn as a physicist. But if you are an evil, wicked economist, you are reborn as a sociologist." (p. xi) *** When Keynes published his theory of the business cycle, some conservative economists argued there was no need for government policy to combat recessions because recessions would be self-correcting. Their argument went as follows: In the face of high unemployment, wages and prices will tend to fall. This fall in wages and prices will increase the real supply of money--that is, the given stock of money in circulation will have steadily rising purchasing power. And this expansion in the real supply of money will in turn lead to an economic expansion. Keynes did not deny the logic of this so-called classical argument; he was willing to concede that in the long run economic slumps would be self-correcting. But he regarded this self-correcting process as very slow, and as he pointed out in a widely quoted but rarely understood remark, "In the long run we are all dead." What he meant was: Recessions may eventually cure themselves. But that's no more reason to ignore policies that can end them quickly than the fact of eventual mortality is a reason to give up on living. (p. 47) *** A trade war in which countries restrict each other's exports in pursuit of some illusory advantage is not much like a real war. On one hand, nobody gets killed. On the other, unlike real wars, it is almost impossible for anyone to win, since the main losers when a country imposes barriers to trade are not foreign exporters but domestic residents. In effect, a trade war is a conflict in which each country uses most of its ammunition to shoot itself in the foot. (p. 287) |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!