|

|

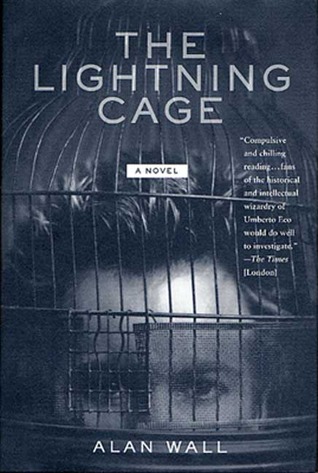

The average rating for The lightning cage based on 2 reviews is 4 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2020-05-14 00:00:00 Alicia Gluckman Alicia Gluckman'The retention of memories by the melancholic type' (Vintage, 200, p.76). Sounds right up my cranial fracture. I cannot be partial in this review: Alan Wall is my tutor at uni, and my dissertation supervisor. It would be disloyal for the novice to criticise the master, or perhaps even to presume that far. But I shall endeavour nonetheless, because it is one of my favourite words. To endeavour. It sounds august, noble, the right thing to do. Yet critical thought is largely what I am being taught; that and the appreciation of literature from various perspectives, or even just for itself, for the very love of the idea, of all those ideas, some stunningly expressed. Even so, do I have the tools, the language, the knowledge to criticise such a novel by someone with a far greater literary history and linguistic trove than I? Well, yes, from the point of view that any reader has such a right, and authors leave their babies in full sunlight, figuratively, expecting the shade of at least ignorance to protect them from the full glare. All that aside, this is rich writing, demonstrating a finesse of linguistic memory that seems to be natural reflex. There are many classical and literary allusions, many causes for recourse to a dictionary; but that is only an enriching experience, after all. Remember when you first read books, the number of times you turned to the encyclopaedia, with relish. Relish is the word. Alan Wall serves you a feast of language, and it's yours for the savouring, or the ignoring. Patience always bears fruit, effort is required to push yourself. I actually enjoy this challenge, and when the time comes when you don't want to look up another word, well, you're just not reading right - or not reading the right thing at the wrong time. The assurance of the prose, the conferral of the linguistic richness, the trains of thought, remind me of Iain Banks or Ian McEwan at their most engaging: engaging the mind, leading into a world built incrementally like a mosaic, developed and revealed like pentimenti beneath an old, dark patina. If you don't want to take this journey, haven't the energy to follow the process of thought, don't want to feel pushed through the testing of your responses, read something else. Sometimes the books that challenge you most, to the point of impatience, delve deeper in the psyche, reside there, leave a mark, a footprint, lingering like a hare's pawprint in the wet dew of morning. We are, after all, grown men and women. With unfathomable mimetic reserves. I have no problem with all the aforesaid, indeed, I welcome it, enjoy the reading experience. My problem is with his subject. Taking a semi-autobiographical - one must surmise - present fictional character, Christopher Bayliss, and blending in a retrospective pseudo-scientific semi-religious figure (as our present narrator, now in absentia, is a lapsed priest) couched in an esoteric investigation into a niche period and figure of poetry requires a certain focus. The question is, are you interested in a semi-historical biography of a near-genius having a series of nervous breakdowns-cum-religious-ecstasies? But then again, what was Blake's inspiration, which drew such weirdly wondrous poetry alongside the Brucknerian grandeur of his slab-like art? Precisely the same, of course. It is merely that religion is complex enough as it is, even in its largest generic doctrines, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and so on, let alone the convolutions of its internecine denominational differences. So a syncretic religion? That is another layer of abstraction perhaps too difficult to mine. But we do, because somewhere twisted in there among the strands of the Fall and myth are polyps of truth, igniting sparks of intuitive igneous comprehension, flaring scintillas of recognition. So we see the mind of Pelham, either in feverish gouts of furious output, mithered by his tormenting spirits, or in his interstitial calms of recovery. Either way, because the common man cannot understand, it doesn't mean he's not worth studying. Especially when he displays both prescience and demonic possession during his fits of relapse between the mercies of remission. And so Chilford leaves him to his own devices, alone but for two servants in the great Palladian villa, like a spectral haunting, free to follow his own meanderings and musings. Meanwhile, Christopher Bayliss is gradually moving back into the known world, moving in his artist girlfriend, getting up a career, then easily, almost dismissively, risking both. And so the duel narratives go. 'There are no coincidences, only a veined complexity sometimes too deep to fathom' (p.182). In this novel, which discusses God and madness - yes, as though they were opposites - in the dissolution of its two principals, God is an 'ontological singularity' (p.100), which is as good a way of defining that presence which, whether we believe or not, we imagine up there somewhere, like the sun at midnight or a black hole that emits heat radiation, there, extant, but not directly visible. And madness is? Possession, at its worst, or Satanism. There is a direct if obverse correlation. The pattern of the alternating narratives starts to make sense. Both are lonely people who cannot quite integrate into the real world; the one possessed, the other fallen. Both either cannot fit into the world's own ordered chaos, or find it too complex to navigate, or simply haven't met the right people to ground them, or have the good fortune for them to stay. But despite all the melancholia and madness - perhaps because of the latter - it is often funny. The hermitic antique bookseller shouting at all his customers who try the door to buggar off; the postman's kind enquiry as our protagonist slides into eremitic seclusion, the house almost devoid of furniture now, the dust become a kind of fungal infestation, definitely alive, braving a timid silent incursion over everything, like the unknowing slippage into reclusive senility. Sad, but funny. I enjoyed Bayliss's musings and stupid innocence. I didn't enjoy the Pelham-Chilford strand. That caused me a big problem. Not least because, without the sacerdotal wherewithal, I couldn't follow parts of it. Overall, though, it was - aside from being an erudite literary work - a pleasure to finish. It was very well written, and made me realise that while certain prominent and successful authors write books worse than their best - though always very well written - works such as The Lightning Cage seem to be lesser simply because less well known. There's no justice, there really isn't. |

Review # 2 was written on 2008-08-09 00:00:00 Karen Kirdem Karen KirdemIf I am not mistaken it is in this novel that the character describes a shoe box full of post cards the family sent from their holidays to their own house. I found that such a beautiful habit that I now have my own box. "Perhaps freedom really did come from renouncing commitments, even though one wasn't permitted to mention the fact." |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!