|

|

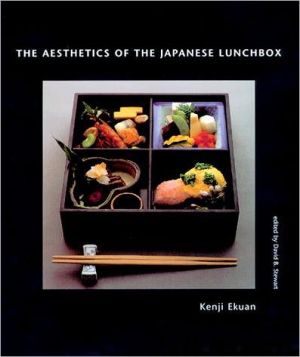

The average rating for The Aesthetics of the Japanese Lunchbox based on 2 reviews is 3.5 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2015-06-04 00:00:00 Andryuhin Andryuhin Andryuhin AndryuhinA very dense book. Basically, everything Japanese is wonderful and so involved and esthetically pleasing and well considered. Okay. |

Review # 2 was written on 2008-04-18 00:00:00 Robin Mathews Robin MathewsAzuma's theoretical analysis of Japanese 'Otaku' culture provides some useful insights into Japanese intellectual life, 'applied' post-modernism and a phenomenon which, like rap from the other side of the world, has spread with globalisation. The footnotes are as valuable as the text. It is perhaps a sign of that spread that my daughter (English) was able to point out quite quickly that two illustrations (of images of girls from Urusei Yatsura and Sailor Moon) had been transposed. It seems that the kids are sharper than the academics on matters of actual content. Unfortunately, like so many works about the post-modern, the book is marred by Theory. Azuma has some important things to say about the end of the modernist project and of grand narratives but he over-relies on Kojeve and he seems desperate to assert his own authorial presence over the data. Kojeve and the Neo-Hegelians represent a particular bug bear of mine (their desperate attempt to impose authorial rights on history strikes me as the last fling of a redundant academy) but equally awkward is Azuma's own instinct to over-analyse and model. The section on multiple personality as analogue for Otaku modes of thinking is mildly embarrassing though this is a rare lapse. What Azuma fails to understand are the power relations implicit in the internet revolution insofar as it allows us choices about value. He is excellent on identifying the role of desire rather than need in post-modern internet culture but he under-estimates the positive role of Japanese popular culture in opening up the space for personal psychotherapeutic solutions to living under conditions of excessive socialisation. He strikes me as still ambiguous in his attempt to remain objective about phenomena that are best understood subjectively. What we have to ask is not why 'Otaku' works in Japan but what it means insofar as it has been adapted (again, like rap) amongst entire generations overseas. His analyses are sound and informative but he seems to find it difficult to see that Otaku thinking can co-exist with a much more grounded relationship with the real world than modernist ideologies have ever permitted their adherents to do. The point of the modernist ideologue is that he cannot but confuse imagination and reality - we see it in the 'Great Religions', in Marxism-Leninism and in Neo-Hegelianism. Today, we see the desperate attempts of politicians to save the Euro as their attempt to force reality into an imaginative strait-jacket. This confusion of imagination and reality is at the root of the great blood-lettings of the recent past. This derives from an obsession with unification - as if the individual mind working within one Heraclitean system can be brought into alignment by force with a Heraclitean world working to different rules. Modern history is the paradoxical attempt to 'will' Cartesian realities be over-ridden so that individuation is not a matter of personal discovery unto death in an unknowable monist materialist world (the way of existentialism) but a social practice built around 'Humanity'. The post-modern revolution provided a theoretical framework for a very profound change in human relations but this revolution continues to use the praxis of modernity because intellectuals, by their very nature, belong to the old world even as they seek to understand the new. Practical, as opposed to theoretical, post-modernism can be characterised by an individual and immediate understanding that the world of socialisation and the worlds of individual imaginations based on immediate desires (where Lacan does have insights) are different but equal in worth. A person is thrust into a world (so much was elucidated by Heidegger) which is constructed by others. Alienation is the recognition that this social world (since the material world is merely the satisfier or denier of needs) does not accord with the inner desiring self. Socialisation (for many and often sound reasons) blocks desire and (under modernism and earlier systems) went so far as try to police desire by socialising the inner mind of persons. Even today, liberal ideologues do this as various forms of political correctness and the constant process of engineering consent. The corporate system lives in the half world between systems, simultaneously trying to manufacture desires and respond to desires that are not manufactured. The market has moved on from the satisfactions of needs, through the creation of desires (and needs) to the satisfaction of desires not of its own making. The power has shifted to the person desiring and this confuses a whole class of intermediaries who made choices for others. The market (by recognising the value of desire) and then the internet (in enabling the desirer access to massive numbers of constantly adaptable and recursive objects of desire) has allowed the young (who will be old one day) the ability to choose 'destinies' and 'identities'. The modern liberal mind is suspicious of the market and increasingly of the internet (except as a directed tool) but it actively loathes the idea of persons floating between and around multiple identities and destinies instead of locking themselves into some socially definable category. Think of the difference between the Generation of '68's determination to class people as gays or blacks or jews and the floating identities of people who play with many sexualities, cultural allegiances and spiritual paths in shifting tribes. The discomfort of the former becomes clearer. The 'modern' Liberal wants the liberation of a rational person who is equal and objectified within a total humanity. The 'post-modern' acts as if he is already liberated as a person operating beyond reason, equal in praxis and with no sense of being anything other than one of many thinking animals. Liberals understand that the post-moderns are highly creative and radical in thought but deeply conservative about social relations and change in the real world. The post-moderns choose to accept reality as it is and construct complex and creative private lives in floating communities or tribes. Azuma grasps much of this. The book is worth reading for his descriptions of how one version of post-modern culture operates, perfectly harmlessly, within a major new paradigm for productive relations which the 'moderns' are now busy trying to put back in a box marked 'controlled zone'. Whether they will succeed or not is not known but it will be sad if elites re-capture the high ground they have abandoned and try to impose 'grand narratives' that turn the 'new humans' (closer to their animal desires and so stronger) back into objects again (and so weaker). A surprisingly readable book for a translation of a text in post-modern theory, it is not quite the masterpiece that it could have been because the author allows himself to get lost in the intellectual struggles of his own country but it is well worth reading. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!