|

|

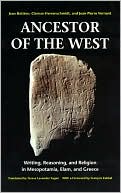

The average rating for Ancestor of the West: Writing, Reasoning and Religion in Mesopotamia, Elam and Greece based on 2 reviews is 4 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2019-10-31 00:00:00 Gregory Bennett Gregory BennettAmong this recensionist's pleasanter childhood memories was poring over the colorful topographical maps in his mother's old historical atlas from her college days at Saint Mary's by Edward Whiting Fox (Oxford University Press, 1957). For the boy and his mother, the origin of civilization was a fascinating topic, only enlivened the more by exotic place names such as the Tigris-Euphrates river valley and peoples such as the Mesopotamians. This all would blossom into a serious interest, when an undergraduate, in archaeology and the ancient history of the classical and late antique worlds. Consequently, he could not but be favorably inclined when coming across the present little volume by Bottero, Herrenschmidt and Vernant. The three authors review the contribution of the Mesopotamians and their successors from the point of view of the rise of writing, religion and mythology, paying attention to the'perhaps surprising'implications these early developments should have for us today. Bottero starts off with an admirable account the birth of civilization and writing in ancient Assyria and Babylonia. His observations on the connection between the physical environment and the spiritual temper of these peoples'initially, Sumerians and Akkadians (who were Semites)'are masterful, and recall Herder's sympathetic treatment of the Egyptians, Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans in his 'This too a philosophy of the formation of humanity' of 1774. Of particular interest is Bottero's reconstruction of the Mesopotamians' religious milieu from the extant cuneiform tablets of oracles and the Atrahasis myth. They were'he contends'more empirical and rational observers of their world than one might at first suppose, and one can well wonder whether modern men and women in our day have advanced very far from superstition after all'pace the Enlightenment!'or, indeed, whether there may possibly be a rational core to superstition (as, in another context, it ought to be pointed out against silly thinkers like Carl Sagan that it is quite possible to be an intellectually sophisticated Hindu and still to believe in some sort of astrology, as indeed many do even today). Bottero's most controversial point is that by accustoming people to the idea of logical consequence of an observed event (or sign), the oracles presaged the formulation of the syllogism at the hands of the Greeks and thus the scientific tenor of Western civilization taken as a whole. From his archaeologist's point of view, it is not satisfactory to trace European culture back to its twin sources of the Greeks and the Jews, but one ought to go all the way back to the Mesopotamians. Herrenschmidt's contribution raises very profound reflections on the spiritual implications of a culture's writing system, whether a syllabary as for the Mesopotamians and Elamites, or consonantal for the Hebrews and Phoenicians or fully alphabetical as for the Greeks (and, in their sequel, for us). She also portrays a fascinating picture of Zoroastrian religion and its successors in Persia and Iran. Lastly, Vernant, in his chapter on myth and reasoning, sketches the arc of Greek culture from Mycenaean to archaic and classical times and raises some interesting points for reflection. For instance, what does it mean that the early pre-Socratics composed their philosophies in verse? Is this not, partially at least, in conflict with their supposed scientific temperament, which is to say, their methodological exclusion of the mythological? Vernant's closing chapter on political power in the polis is of less vital concern to this recensionist; it is not so clear to him that the Greek polis did exclude the sacral dimension of political power, although to be sure it is less overt there than in the Orient; see, for instance, Sophocles' Antigone. All around, an intriguing and unconventional account of wonderfully ancient history and cultures! |

Review # 2 was written on 2012-10-21 00:00:00 Terry Wildey Terry WildeyThis book includes 3 essays originally written in French and translated into English. I found Bottero's essay on Mesopotamia very accessible to someone who has read a bit of Mesopotamian history and Vernant's essay on Greece fairly accessible to someone who has read a bit about early Greek history. Herrenschmidt's essay on Elamite, Persian, Greek and Hebrew writing and thinking, however, includes a bit more linguistic detail and what I assume is valid linguistic theory (but might just be a lot of academic hooey...) than I was able to enjoy. If sentences like this make sense to you, perhaps you'll get more out of the essay than I did: "This separation of language and the signs used to write it, this independence between the sign and the syllabic unit, brought about an irreversible movement toward the appropriation of language by people." (p. 85) "Consonant alphabets mean significant progress in humans' appropriation of language, but they did not inscribe the sounds in the body of the speaker, but halfway between his body and his speech." (p. 96) |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!