|

|

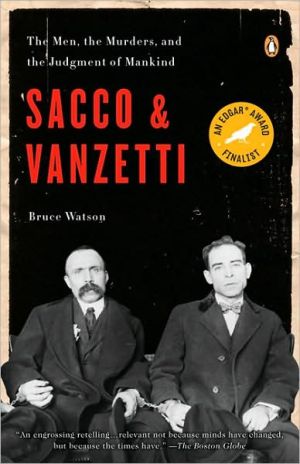

The average rating for Sacco and Vanzetti: The Men, the Murders, and the Judgment of Mankind based on 2 reviews is 4 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2017-11-29 00:00:00 Jos Heinricy Jos HeinricyFascinating book! Would definitely recommend this one. |

Review # 2 was written on 2011-04-26 00:00:00 Scout Lee Scout LeeJohn Dos Passos astutely wrote that Americans are two people: those capable of contextualizing what they read and hear with their republican values and those hopelessly distracted by base prejudice at the expense of good citizenship. Dos Passos's quote is repeated two or three times in Sacco and Vanzetti and is the base of the book itself. I find it interesting that one could also say about Bruce Watson's monograph that Sacco and Vanzetti is two books: one that contextualizes the trial with American values and the times and one that gets bogged down in detail. The 1920s is a fascinating and under-served period in American history. If for no other reason than we became the people we are today in the 1920s, since... "Nearly every amusement that would dominate the twentieth century - radio, TV, sporting spectacles, pop psychology, home appliances, youth culture, crazy fads, 'talking pictures,' Madison Avenue, Mickey Mouse - got its start during this frantic decade." Much more than the 50s or 60s, the 20s gave us the features we identify ourselves by today. While it may have been Fenno's Gazette of the United States (at the earliest) or Hearst's New York Journal (more likely) that started the shrieking, manic, panicky news cycle, it wasn't until the 20s that polemic causes celibrés ignited international markets with the antics of a certain sample of an unusually reactionary American public. The first part of the book doesn't say as much, but I got a real vibe from Watson that he considers Islamophobia and the right's too cool for brains posture a continuation of the lessons we failed to learn eighty years ago. In the 1920s, some Americans believed that all Italian and Italian-American Catholics were depraved bomb-throwers in a number that approximately corresponds to the number of Americans who believe all Muslims are suicide bombers. Or all African-Americans are lascivious sub-humans with loose morals... Or that all Japanese-Americans are Tojo's spies... Pick your year; it's sort of the same. The pathological defect in the national character believes a small number of loosely related crimes is justification for wholesale racism and bigotry. Not that terrorism is often justified, but America has to re-learn the lesson that further antagonizing the terrorists by abusing the innocent is the wrong way to quell terror. Watson doesn't say it, but the reason Italians, leftists, and the international proletariat stopped planting bombs when Italian-Americans and Catholics were eventually admitted into the American franchise on a more-or-less equal basis with WASPs and the vicious red-baiting of the early 20th century yielded to the Bill of Rights. It didn't stop because our legal and political system really stuck it to the reds. I digress. Someone else wrote a review complaining that Watson seems to believe in Sacco and Vanzetti's innocence because of a personal, liberal agenda. Not really. The case of Sacco and Vanzetti is routinely taught in American classrooms as an example of government corruption in the age of the Harding and Coolidge heydays. The perception of a "frame-up" and political persecution is the standard academic interpretation. So if Watson is speculating on the context of corruption and prejudice in the 1920s, the reader is not out of line finding parallels in the intervening years. That's all I'm saying. And with that, Watson has a pretty good book, here. But the author doesn't rest on sound historiography. He goes into detail of the minutes of the trial and rounds of appeals that is, frankly, grueling. While Watson isn't uncommonly long-winded, he doggedly documents each move in a grim dance involving judicial incompetence, judicial indiscretion, and judicial gridlock. Redundant points aren't consolidated together for maximum effect. Instead, they're cited separately, in chronological order. It makes reading a breezy work of non-fiction a little bit like reading actual court transcripts (which I have to do occasionally, and while it may thrill some it definitely isn't for everyone). This approach is thorough, and cannot be fairly called bad scholarship. But it slows down the tempo and makes a good book suddenly, decidedly. much less fun. That's a shame, because I think Watson has written a book that will be the go-to for undergrads, history enthusiasts, and general interest on the subject for years to come. It's a shame that it doesn't hold the reader as rapt as its subject deserves. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!