|

|

The average rating for All-In-One Teaching Resources Chapters 1-4 (Prentice Hall Mathematics - California Algebra R... based on 2 reviews is 3 stars.

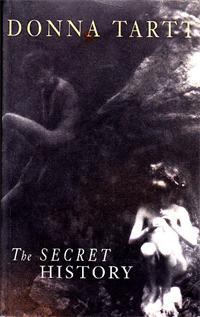

Review # 1 was written on 2019-03-01 00:00:00 Ig Moore Ig Moore[flings myself onto a chaise lounge and wails dramatically] The fact that I’m not a part of an elitist circle of young self-styled scholars who quote Classics over dirty Martinis and toast to living forever and are driven to commit various acts of evil as a result of getting too absorbed in their Greek homework is the real tragedy here. What’s this book about? Murder always makes an auspicious beginning for any good story. Bunny is dead, and his friends’ mercenary relief at having him gone didn’t take long before it turned sour. In The Secret History, the venom of remembrance falls to Richard Papen, and the bulk of the book concerns itself with the months leading up to that point. “This is the story I will ever be able to tell,” says Richard, and with that, the still depths of memory come shivering back to life. In the days after Richard Papen sets foot at Hampden College, he is aimless, as unsteady as a poorly made bow, suffering a deep pang of loneliness and dejection. But then all of a sudden, at the center of it all, in a pocket of stillness within the simmering nest of his life, was them. A clique of rich and sophisticated classic majors who drift about with their heads full of myths, always at least half-lost in some ancient story, and who worship at the shrine of their highly eccentric professor, Julian Morrow. The closeness between them was palpable, and something about that struck Richard with a deep allure. They weren’t exactly unfriendly with the rest of the world; they were just friendlier with each other, and Richard spared no efforts in impressing on them that he could fit in as well. To that end, Richard changed everything, even the fabric of himself—adorning, embroidering, essentially reinventing the less glamorous aspects of his life. He was like a ghost interposing himself between lovers to feel what it was like to be alive, and that so much death would dog his heels soon afterwards is a brutal irony. As in any group, there is tension, of course, but it never grew very heated between them. Neither did it ever quite abate. It was the tension of minds meeting, of differing interests, not the tension of a world about to become terribly complicated, ending in tragedy, six souls forfeit. A world where murder and lies and treachery were nothing but a currency they used to pay for the rest of their lives. Let God consume us, devour us, unstring our bones. Then spit us out reborn. Everything about The Secret History is as crisp and elegant as freshly pressed silk. So skillfully and engagingly that I was quite disarmed, and with writing surfeited with such beautiful delicacy I sometimes had to stop and stare, Tartt led me deftly from page to page, from chapter to chapter, through a messy, mad tumult of memories, like reflections in boiling water. The Secret History’s flow is hypnotic, and Tartt sweeps the reader, with vivid and tender enthrallment, into a reverie about beauty and mortality and godhood, the ghosts of the books and writers she admires seeming to slip into the cracks between the lines, and, like many operas, the climax is tragic but beautiful. It takes a great amount of authority to write like this, and Tartt has authority in spades. Even when the plot lags, she finds a way to enliven the telling of her story: this is the kind of novel that deserves to be drawn out and savored, however much tempting binge-reading it may be. The Secret History is a romantic dream of doomed youth that cared nothing for sense or self-preservation and "sailed through the world guided only by the dim lights of impulse and habit". The dynamics between the characters will surpass your wildest definitions of dysfunctional. They were darlings and vipers—caught in a twisted pantomime of ambition and self-importance and their abominable fulfillment. But they had their own gravity, and were the center of Richard’s small, surreal galaxy. Richard Papen chronicles his own tale, beginning with Bunny’s murder and his involvement in it—the admission so simple, so unornamented, unmarred by grief or regret, as if it were just a dry fact that could be taken out and studied without emotion. From then, his mind starts picking at his memories, like fingers at a knot, with the sort of cultivated assuredness you should know better than to follow into the dark. This is how it happens: one minute you see the story as Richard tells it, his remembrances thrumming at the border of passion and desperation, but with a mental step to the left, and with the right perspective, everything suddenly flips, everything finds a new interpretation and, in an instant, the whole view changes. Suddenly, you can glimpse the lie, shimmering and perfect. You realize that there are too many images reflected in fragmentary style on the surface of it that don’t really belong there. It’s the things just beneath his words, as though Richard wrote them down, erased them, and scribbled over them. Reading the latter half of The Secret History, I felt left out of the tale, sensed it slipping from my hold and altering in ways I hadn’t anticipated, then—at last—realization dawns: Richard is many things, foremost among them is that he’s a damn good unreliable narrator, and that’s one of the biggest triumphs of this novel. I’d been slow to grasp it, but when I seized it, that thread of truth, it became a sort of struggle to reconcile what I thought I knew with what I’m seeing unravel before me. In The Secret History, a curtain is drawn back in Richard Papen’s inner theater and his storytelling mind gets to work: in the mists of his memories Camilla Macaulay was quiet and had a shadow’s talent for passing unremarked—she was a brittle, sharp-edged fragment by herself, always mentioned alongside her twin brother, Charles—while Henry Winter drew all eyes like a flare. For Richard, Henry had been a sunray, illuminating every facet of his world. Henry was beautiful, impassive, untouched by emotion or pain. There was always something unfathomable about him, something as inscrutable as the turning of his thoughts. He was the brilliant autodidact and linguistic genius who seemed to suffer people’s ignorance of ancient Greek as though it were a physical blow and whom Richard wanted to impress with a compound interest of human desperation (which, in many senses, later becomes his undoing). Julien Morrow wasn’t seen as anything but relentlessly benign. Francis Abernathy was only a rich boy who assumed the world was his oyster because he’d gone to the right schools and mixed with the right people and whose sexuality Richard—for reasons he cannot explain to himself, but which are pretty clear for discernable readers—was fixated upon. And, of course, Bunny who was a terrible person with a terrible affinity for reaching inside one’s innermost self and depositing, with wicked relish, gifts of self-loathing and insecurity, and whose murder Richard might have borne with more fortitude if Bunny hadn’t been so horrible. All this knowledge, however, soon wavers and falters, growing feebler and harder to maintain, and that’s when Richard—as well as the reader—begins caroming upward into a state of heightened lucidity: Richard has been most naïve in those days. He trusted too easily and could not see into the cracks of the world, and his imagination has fashioned the quintet into something they were not, or at least, they were more than his depthless perception of them. However sweet her nature seems, Camilla is not soft; her edges are gleaming and sharp, and in that regard—Richard realizes later—she is a lot more like Henry. They both know how to reach into one’s soul and play their emotions like a harp: Camilla strung her admirers along like fish on a line, and I often marveled how close she could slice the difference between hate and love. Henry sowed enough seeds to ensure Richard would know to follow; he’d tested his loyalty, prowling the edges of his trust, looking for a crack—but it all held. It’s almost unnerving—the way every argument turned out meant whoever did Henry’s bidding got a little more of Henry’s favor, and whoever didn’t lost it completely, the way Bunny had become a single rope twisted from the whole, hanging before their minds’ eye—separate and other—because Bunny committed the unpardonable sin of disobedience. There’s also more to Francis and Charles than meets the eyes. Francis’ character was a quiet, still pool that held everything safe in its depths, but, occasionally, the extravagant façade would betray his plunging insecurity and frailty which ring like a bell in his frequent “are you mad at me?” and the way his hands often hang numbly, unmoving, by his sides instead of acting. Julian Morrow, whose words they all took as gospel, is a liar and his sinister figure permeates the whole of this tragedy. As for Bunny—and there is really no way to beautify the following—he’s an asshole. There was a hole inside him that needed to be filled with other people’s misery. But he hasn’t always been an asshole, and Richard has to dig deep to unearth that memory where he kept it buried under his self-serving desire to legitimize their crime and taper his own guilt, to realize that no currency would ever make him and Bunny even. But strangely, it’s Charles’ transformation—more jarring than a body turning itself inside out—that snags at me the most: how this boy, who had no sins anyone knew of or could guess at and whom Richard once describes as “a kind and slightly ethereal soul”, could have the capacity to become so horrible, everything that was kind in him suddenly driven out. But for all Charles’ faults, I would argue that out of the five of them, he is the one who felt the rawness of their crime most keenly, or at least more outwardly—and the fallout is an utter heartbreaker. I could be wrong. I could be so spectacularly wrong about everything, but that’s just it: one of the things I most relish about this book is how you become the characters, breathing life into them, creating them from the faintest scrapings of information that you’ve been given—the harder you think, the more you see, and it just keeps getting more productive. In this sense, and many others, The Secret History also relentlessly ponders the power of beauty to dazzle, to cast a ghostly light over a world that is deep-down stripped of color, and, in particular, to make those people who possess it seem smarter than they may be. We are always drawn to the lure of beauty, no matter the cost, and Richard Papen—with his "morbid longing for the picturesque at all costs"—was no exception. The quintet’s willful dedication to the ideals of art and beauty—which will eventually steer their fates towards calamity—held its own fascination, and a part of Richard wanted to do whatever they asked him to do. And it was a loud part. Back then, it seemed like a part worth listening to. “Beauty is terror,” writes Tartt, perhaps portending how the beauty that once shone like a flame, drawing Richard’s eye against his will would in time, like acid, eat away at the flesh of their souls. That it would, one day, all turn into ashes and ruin. If you liked this review please consider leaving me a tip on ko-fi ! ☆ ko-fi ★ blog ☆ twitter ★ tumblr ☆ |

Review # 2 was written on 2008-09-13 00:00:00 Jerry Lowery Jerry LoweryThis novel, like so many other first novels, is full of everything that the author wants to show off about herself. Like a freshman who annoys everyone with her overbearing sense of importance and unfathomable potential, Donna Tartt wrote this book as though the world couldn't wait to read about all of the bottled-up personal beliefs, literary references, and colorfully apt metaphors that she had been storing up since the age of 17. The most fundamentally unlikable thing about this book is that all of the characters -- each and every one of them -- are snobby, greedy, amoral, pretentious, melodramatic, and selfish. The six main characters are all students at a small and apparently somewhat undemanding college in Vermont, studying ancient Greek with a professor who's so stereotypically gay as to be a homosexual version of a black-face pantomime. In between bouts of translating Greek, the students end up murdering two people, and then devolve into incoherent, drunken, boring decay. The best thing I can equate this book to is the experience of listening to someone else's dream or listening to a very drunk friend ramble on and on and on, revealing a little too much awkward personal information in the process. The climax of The Secret History's narrative was around page 200, but the book was 500 pages long. So, essentially, this book contained 300 pages of scenes where the characters do nothing but drink alcohol, smoke cigarettes, go to the hospital for drinking so much alcohol and smoking so many cigarettes, get pulled over for drunk driving, talk about alcohol and cigarettes, do cocaine, and gossip about each other (while drinking alcohol and smoking cigarettes). Tartt's writing was sometimes genuinely good at establishing a thrilling and suspenseful mood, but other times, especially toward the end, her writing became the kind of self-conscious, contrived, empty prose that I can imagine someone writing just to fill out a page until a good idea comes to them, kind of like how joggers will jog in place while waiting for a traffic light. That kind of writing practice is fine...as long as the editor is smart enough to cut it before the final copy. The last 300 pages were the authorial equivalent of that kind of jogging while going nowhere, and it soured the whole book for me. In the book's attempt to comment on the privilege, self-interest, and academic snobbery of rich college kids in New England, the book itself comes to be just as self-absorbed and obsessive as its characters -- it turns into a constant litany of unnecessary conversations, sexual tensions that go nowhere, purple prose descriptions of the landscape, contrived plot twists that fizzle out, and forced, overblown metaphors. The confusing part was that Tartt seemed to identify with (and expect us to identify with) these students -- not to admire them for murdering people, obviously, but to respect and envy their precious contempt for everything modern and popular, as though they lived on a higher plane than normal people. The cliche of academic types being remote from the mundane world and out of touch with reality may have a grain of truth to it, but Tartt took that cliche way too far. The story is set in the early 90s, and yet some of the characters had never heard of ATMs, and they still wrote with fountain pens, drove stick shift cars, cultivated roses in their backyards, wore suits and ties to class, and said things like, "I say, old man!" Did I mention that this story is set in the early 90s? It got to the point where all the anachronisms came to seem ridiculous and gratuitous. Ostensibly, the point of the novel was to critique the point of view that privileged academics are somehow superior to the average person, but Tartt seemed too enamored of her own characters and the endearing way they held cigarettes between their fingers to really allow that kind of critique to be successful. Maybe Tartt's second novel managed to get away from the claustrophobic selfishness of The Secret History, but I don't feel up to reading it after this. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!