|

|

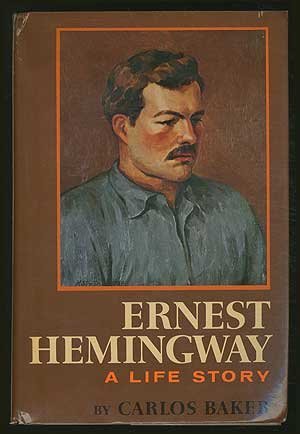

The average rating for Ernest Hemingway Pt. 1: A Life Story based on 2 reviews is 4.5 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2014-08-06 00:00:00 Dennis Pikop Dennis PikopBecause I’m a son of a bitch. -- Ernest Hemingway, late 1926. Truly. The Hemingway that emerges in Carlos Baker’s mammoth (714 pages of small print, excluding notes) is virtually impossible to like, or even – it seems -- to pity (though that changes when it comes to his last feeble year or so). The four wives (Hadley, Pauline, Martha, and Mary), the blown up marriages, the blown up friendships, the drunken arguments, the literary knifings, are all here. I don’t sense any attempt by Baker to pull punches, though I'm sure later biographies have unearthed some real whoppers. In other words Baker has no axe to grind, but dutifully assembles the stuff (as in everything) of Hemingway’s life and records it – with a tone that is neutrally sympathetic -- in chronological fashion. On occasion Baker will linger over a piece of writing, and add some thoughtful insights, but never for more than a few lines, or a paragraph. Generally this is not a literary study, but a biography on the incredible life of a major literary figure. I've noticed that some reviewers have complained that the sheer avalanche of information is simply too much. I disagree. Hemingway was a prolific letter writer, and that’s where a large part of this biography comes from. Also, a lot of the physical descriptions in Baker’s book sound a lot like Hemingway. You get the sense that Baker is often paraphrasing – or even mimicking EH. If so, it’s not a weakness in the biography, but a strength. As Hemingway’s life unfolds, you can see how Baker follows up on long running preoccupations of Hemingway, with suicide being the primary one. Time and again Hemingway reflects back on this, with the knowledge that suicide is a family tradition. His father’s death by his own hand, at the height of Hemingway’s popularity, only cemented this notion in Hemingway’s mind. His ending is certainly no shock. And then there are Hemingway’s issues with women, starting with his mother, Grace (“the bitch”). Though Baker doesn't really go there, one can’t help but feel that the first two marriages (Hadley and Pauline) were simply calculated moves in order to facilitate his writing career. Hadley had a modest pension or trust which allowed for her and Ernest to go to Paris. It was a hard life, but a magical one that captured a special time and place. It’s there that Hemingway, in the blue light of morning, before the nearby sawmill started up, learned to craft perfect sentences that married compression and precision into something complex and new, even poetic. An early example that Baker cites is “Paris, 1922” (see "Six Sentences" link below). These were new for me, and wonderful, strongly suggestive of the prose-poem interludes in the early collection, In Our Time. Then the baby, “Bumby,” comes along, compounding the difficulties of living on a tight budget and not yet making enough money to live on. It’s at this point Pauline Pfeiffer enters the picture. When this phase began, I set the book down for a few days. I have always felt Hadley got the raw end of it, and Baker records nothing here to change that view. If anything, he underscores it late in the book when Hemingway admits to a house guest that he married Pauline for the money (her family was very well off) so that he could continue in his career as a writer. This calculated move is not without guilt, and Hemingway, in later years, shows regret over blowing up his first marriage. The Pauline Pfeiffer phase begins shamelessly as the two pose as pious Catholics (the first marriage to Hadley didn’t really count). Pauline is sincere about her Catholic faith (perhaps too sincere), and Ernest tries, but the reader never believes it. In the end, I suppose it was the best thing that could have happened to Hadley. She would meet a nice guy who took care of her. What follows next is a numbing list of hunting, fishing, and traveling expeditions. The pace is manic. Hemingway cannot stay put for long. Pauline is actually content to be a homebody in Piggott, Arkansas. But not Ernesto! He does discover Key West (via Pauline), and the wonders of endlessly shooting shit in Wyoming (400 jackrabbits – how is that possible? And why?) It does prove to be a productive period for him, and he cranks out a number of short stories, lucrative magazine pieces, an uneven "novel" To Have and Have Not, and an uneven travel piece Green Hills of Africa. I think these are mid-level Hemingway efforts that are certainly worth a read, but not close to the chiseled perfection of those early stories and two novels (The Sun Also Rises, and Farewell to Arms). Now comes the Martha Gellhorn phase (“bitch” number 2). Whatever one feels about how Pauline hooked her man, there’s no doubt she was a good wife – and mother to two of Hemingway’s children. But that kind of static domesticity, no matter how much hunting and fishing punctuates it, shows Ernest losing his edge, drifting into middle age as a writer past his prime. When he meets the predatory Gellhorn, an attractive and up and coming journalist, he proceeds to blow up his second marriage. This process actually takes years to accomplish, thus rubbing Pauline’s face in it for quite a while, but this process is helped along by the war in Spain. Hemingway the Writer becomes invigorated by the war, and spends considerable time in Spain, often in the company of Gelhorn. Stuff happens and goodbye Pauline. It is during this period that Hemingway gathers himself for one monumental writing effort which would result in For Whom the Bell Tolls. This book is Hemingway’s intended big book, his War and Peace. It’s not his best, but it’s the one that makes him a lot of money both in sales and a movie deal. It’s also the one novel where he gets beyond the smaller, meaner canvases of elevated autobiography (something his critics were hitting him for) and addresses the political issues of his day. To his credit, he never really buys the Communist line, while at the same time maintaining a solid hate for the fascists. The marriage to Gellhorn soon follows. This marriage has to one of the worst pairings ever. We’re talking Ted and Sylvia dysfunction. Different issues, but the same level of heat and hate. They both write, but that’s about all they have in common. She does introduce him to Cuba, and a place for them to live – with lots of cats. But she refuses to be dominated, and continues to pursue her career in journalism as the war clouds in Europe gather. It’s at this juncture in Hemingway’s life where I sense the wheels coming off. The writing of For Whom the Bell Tolls has emptied him, and his descent into alcoholism accelerates. He starts in the morning, and keeps it going all day long. Once World War II begins, Hemingway is able to secure a bizarre arrangement with the U.S. embassy that has him patrolling (in his fishing boat) the seas off of Cuba, looking for U-Boats. Booze and grenades, tommy guns, shady characters, and the open sea. Whoo-hoo! Martha, whenever she’s home (not often), is disgusted with both Hemingway and the cat shit. Hemingway does eventually make it over to Europe, and Baker spends considerable time recording these exploits, which are often drunken and madcap. Baker seems to argue that Hemingway actually got physically and mentally better the closer he got to the action, and that the real soldiers often respected his opinions. Beyond danger being a drug, I’m doubtful, but he was probably fun to get drunk with. One weird thing Baker mentions is Hemingway’s accurate sense of impending death to others. During this time Hemingway meets his next wife, Mary Welsh. He’s still married to Gellhorn, but it’s pretty much in name only. The few times they meet, he treats her like trash. The good news here is that she’s perfectly capable of return fire. It’s also during this period that Hemingway suffers a number of severe head injuries. At the time that Baker wrote this book (1968), the knowledge of what concussions can do to the brain was, I assume, limited. But Baker does draw attention to them and Hemingway’s increasingly bizarre behavior. The last years do show Hemingway actively writing, but it’s mostly stuff he couldn't finish and that wouldn't be released until after his death. The one big success story, which is really a novella: The Old Man and the Sea. It was a big hit (book, and later, the movie), and it wins him the Nobel. Toward the end of the book you see Hemingway slowing down, becoming more reflective. I found it interesting how he repeatedly asserted that Faulkner (before WF won the Noble) was the better writer. For someone as hyper competitive as Hemingway, such statements are remarkable, but also indicative of just how seriously he took the craft of fiction. The last years also show Hemingway trying to fend off potential biographers (he thought as a subject, he should be dead first), and traveling once again to Africa. It is here where he suffers two plane crashes, and yet another head injury. The last days are dreary and sad, with Hemingway in the depths of deep depression, being subjected to shock therapy, suffering paranoia attacks and, increasingly, just staring out the window. Mary’s leaving the keys out for the gun cabinet could be seen as incredibly negligent, or simply providing the key that would close the inevitable circle. Six sentences: |

Review # 2 was written on 2017-08-07 00:00:00 Eric Kessler Eric KesslerThere are many aspects of Ernest Hemingway’s character that range from unattractive to outright despicable. The author does not shy away from demonstrating these traits. However, Hemingway led a highly compelling life. He lived in France, Italy, Spain and Cuba; traveled extensively in Europe and parts of Africa. In the U.S., for the most part he was on the fringes - in Key West and the mountains of Idaho. He never lived the high life in terms of luxury, except when staying in New York. This is a complete biography with wonderful passages of how Hemingway’s stories evolved – and then how they were received. We are given many of Hemingway’s wide-ranging activities. What I found interesting, psychologically, was that Hemingway would have a general routine of writing in the morning – and immediately after, switch over to his huge social world of friends, drinking and an assortment of avocations (hunting, fishing, bull-fighting, skiing, travelling...). Hemingway was no loner. It is a remarkable transition to make from the solitary soul-searching of writing. Later in his life Hemingway tended to surround himself with fawning sycophants, which served to increase his bombast. One trait I found reprehensible was his hateful denigration of those who dared to criticize his writing. Former friends would be cast-off with derogatory insults. Often he would ask feedback on what he had written. Woe betides those who were less than complimentary. His editors at Scribner learnt to maneuver through this minefield. It should be mentioned that Hemingway did a lot of his own editorial work on what he had written, revising much of his text. Hemingway spoke Spanish, French and Italian. He had a knack for mixing well in all levels of society – with ranch-hands, privates in the army (Spain and the U.S.), farmers, fishermen (Key West, Cuba); he was no snob. They provided him with characters for his books. He was a keen observer and would probe during conversations, gathering material for future use. There are a lot of details in this long biography of food, drinking (lots of it), marriages and divorces (three of them), friends encountered (many), and then enemies made – and hunting, fishing, and bull-fighting (one of Hemingway’s least admirable activities I feel). We are given a full picture of this fascinating man and writer – and a 20th Century journey. Page 277 (my book) Ivan Kashkeen a Russian translator, 1935 “even under his changing names , you begin to realize that what had seemed the writer’s face is but a mask... You imagine the man, morbidly reticent, always restrained and discreet, very intent, very tired, driven to utter despair, painfully bearing the too heavy burdens of life’s intricacies.” The very mirthlessness of his spasmodic smile, said Kashkeen, betrayed the tragic disharmony inside Hemingway, a psychic discord that brought him to the edge of disintegration. Page 528-29 excerpts of Ernest Hemingway’s written speech for his Nobel Prize in 1954 “Writing at its best, is a lonely life. He [the writer] grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day. For a true writer each book should be a new beginning where he tries again for something that is beyond attainment... Then sometimes, with great luck, he will succeed... It is because we have had such great writers in the past that a writer is driven far out past where he can go, out to where no one can help him.” |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!