|

|

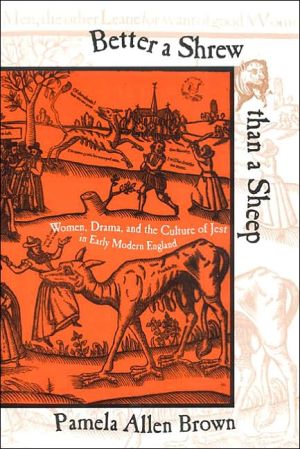

The average rating for Better a Shrew Than a Sheep: Women, Drama, and the Culture of Jest in Early Modern England based on 2 reviews is 4 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2016-11-18 00:00:00 Gail Taylor Gail TaylorThe most shocking thing was to find out that some women were financially independent in the 16th century and that no these women weren't of high social status. |

Review # 2 was written on 2019-01-25 00:00:00 Chris Dillingham Chris DillinghamWhen I saw Henry VI part 1 last year at the Shakespeare Festival, I asked for suggestions to read about the trilogy, since I could not find very many articles about these plays, and this book was the one that was recommended to me. I'm really not sure why, because it has very little mention of these three plays, but it was one of the best secondary works on Shakespeare I have read (and I've read dozens in the last few years.) The book is concerned largely with arguing against other scholars, something I generally don't like, but Rackin's arguments, despite the obligatory nod to postmodernism, are based on facts and common sense rather than theory. She is largely trying to defend the political feminist theory of the 1970's, which emphasized the agency of women that has been partly hidden by male oriented historical writings and documents, against the apolitical academic feminism of the 80's and 90's, which forced the plays (and the historical context) into a straitjacket of "exposing" the texts as arguments for patriarchal ideology. She begins by admitting that the official ideology of Shakespeare's time was patriarchal and restrictive of women, as has been amply documented in works of the time (largely of course written by clergymen -- what would future historians think about the role of women today if their main sources were fundamentalist preachers and Demopublican politicians?); but she shows (with evidence) that that official ideology was not universally accepted, and perhaps not even the belief of the majority of the population, and that it certainly did not describe the historical actuality. Among the interesting statistics she gives, from various regions of England, are that 16% of all the households were headed by women (perhaps not surprising when one considers that there are far more widows than widowers even today, and that was even more true following the Wars of the Roses and the religious wars and persecutions which followed them under Henry VIII, Edward V, and Mary I); 48% of the known apprentices were girls rather than boys; most of the executors of wills were women (so great a preponderance that the female term "executrix" is often used incorrectly even when the executors were men). She points to texts and drawings showing that women were working outside the home, and even in what are now considered as "traditionally masculine" trades. She argues that the confinement of women to the domestic sphere was just beginning in the seventeenth century, largely due to the rise of Puritanism (and of course, though she doesn't emphasize it, nascent capitalism, which is hard to distinguish from Protestantism at that time). (Another interesting statistic she quotes, although it's not relevant to Shakespeare, is that about 17% of all the mass-market paperbacks sold in North America are Harlequin or Silhouette romances. Ugh) While many critics interpret the plays as intended to appeal to the insecurities of a male audience, she points out that at least half and perhaps more of the paying customers in Shakespeare's playhouses were women -- even on a purely economic basis, it makes sense to interpret the plays from the perspective of women spectators. She then shows how the standard recent interpretations have twisted the obvious meanings of the plays to fit the thesis that they were arguments for patriarchy. She uses the example of recent interpretations of As You Like It as about the "exchange" of daughters to make alliances among fathers, when in fact none of the marriages in that play are arranged by fathers. She also has good (and iconoclastic) discussions of the use of boys to play women's parts, of the references to breast-feeding in the plays (which was a controversial topic at the time), and new analyses of, among other things, Antony and Cleopatra and Sonnet 130. While she sometimes exaggerates and there is some academic jargon, this is a refreshing antidote to some of the academic articles I have read over the years. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!