|

|

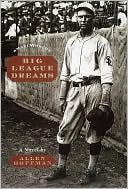

The average rating for Big League Dreams based on 2 reviews is 2 stars.

Review # 1 was written on 2017-07-12 00:00:00 Sandra Fenton-goss Sandra Fenton-gossThe second last novel he published in his lifetime, A FIFTH OF NOVEMBER is also the final of Paul West's many historical novels, a subsidiary strand running through the man's body of work, part of that whole teeming corpus cobbled-together over the course of more than four decades and consisting of, in addition to novels that did or did nor deal with major historical events from eras variously distant, poems and essayistic non-fiction stuff and all sorts of disparate demonstrations of learning and acuity, the author's overall 'project,' shall we say, having been characterized, in the words of Lore Segal, cited over at his Wiki, by "unsettling nonuniformity." I have only recently discovered Paul West. It is the novels to which I have come first, my yen being what it is, many things attracting me to them, their "unsettling uniformity" and purportedly triumphant wordsmithery not the least of it. In short order I have acquired nine West first editions, two of them signed, three of them near impossible to think of as anything other than historical novels, and only one of them nominally non-fiction (though I also have that book's sequel-of-a-sort, which curiously IS classified as fiction). I started with the Alley Jaggers trilogy, three novels published between 1966 and 1972, set close to contemporaneous with those years, and then read West's final novel, 2003's THE IMMENSITY OF THE HERE AND NOW: A NOVEL OF 9.11, which, contrary to what its title might lead one to believe, is ostensibly set in 2004, nearabouts the third anniversary of 9.11 and about one year after said novel's publication. A FIFTH OF NOVEMBER is my fifth West, then, and the first of the historical novels. I also own first editions of 1980's THE VERY RICH HOURS OF COUNT VON STAUFFENBERG, engineered around the 1944 inside-job attempt to assassinate Hitler, and 1991's THE WOMEN OF WHITECHAPEL AND JACK THE RIPPER, whose title I would imagine to be self-explanatory. A FIFTH OF NOVEMBER, published in 2001 by New Directions (one of only three Wests the prestigious publishing imprint had occasion to shepherd), is a novel ostensibly about the infamous English Gunpowder Plot of 1605, commemorated annually in England in the form of Guy Fawkes Day, a morbid bit of arcane carnivalesque that persists to this day for some godforsaken reason, my sister, who lived in London for slightly more than a decade, confessing to me that she was never able to make head or tale of the whole ghastly business. The Gunpowder Plot, or Jesuit Treason, should you not be in the know, was a conspiracy to assassinate, or rather blow sky high, King James, the House of Lords, and everyone in it, carried very, very near to execution by a group of English Catholics led by Robert Catesby, the most famous conspirator being Guy Fawkes, who had fought in the Spanish Netherlands for the cause of the failed suppression of the Dutch Revolt, his legendary status no doubt attributable to his having been the bloke caught red-handed at the scene of the obstructed crime, surrounded by thirty-six barrels of oldschool ordnance, the makings of a hell of a payload. Neither Catesby, Fawkes, nor the eleven other central conspirators in the Gunpowder Plot are the principals in West's novel, though they are certainly on the periphery, even popping in on occasion to go on the record. West will often refer to Fawkes as Guido Fawkes, the sobriquet a byproduct of the man's earlier continental adventures, evidently true to the historical record, and Guido is granted a very squat bit of literary real estate in order to soliloquize: "It is I, custodian of the black powder." The novel's protagonist is actually Father Henry Garnet, real historical personage, originally of Derbyshire, ordained in Rome, by the early 17th century Jesuit superior of England, a somewhat clandestine role, a dangerous place and time. Garnet "thinks of himself as light." He has "a Derbyshire quietness in his demeanor, betokening not the gruff intransigence of the Yorkshireman in the county next door," but this quietness is complimented by "nerves of oak." He is a serious theologian, if an oft pessimistic one, doubtlessly sobered considerably by his experiences, believing that "for the soul to speak, it should have a language of its own, pure and godly, unknown to humankind, and therefore blessing itself in blindest esoterica. Now, there's just the kind of thought to get him damned, socially at least, hoicked out of his hidey-hole and hanged along with hundreds of other mildly dissenting churls." God, he surmises, "presumes to some kind of power, making us invisible and yet, at the same time, even more spiritual than ever, more abstract, more distant, more creatures of the mind than of ritual, splendor, office." Unlike Papist rebels Catesby and Guy Fawkes, hellbent on vengeance and conflagration, Father Garnet considers the "interests of diplomacy." He has a secret and unseemly fixation, practically a botanist's, regarding female genitalia, colouring as this does his close, intimate, but resolutely chaste relations with the devoted Anne Vaux, Catholic recusant and priest harbourer in her own right. Garnet also has an obsession with the limits of his own valour, bordering on prideful. What torture is he capable of withstanding? The question is not an especially abstract one, not even before the Plot fails and the conspirators are being rounded up. Garnet has seen with his own eyes priests hung and/or disemboweled. It's the early 17th century after all: Shakesepare, jokingly referred to as Spokeshave at one point, is active producing masterpieces (OTHELLO, KING LEAR, and MACBETH will appear between 1604 and 1606); Protestantism has assumed its hegemonic consolidation, Rome on the outs; to end up hung, drawn, and quartered is an all-too-customary fate. Father Garnet has had occasion to counsel the would-be insurrectionists, and he has cautioned them against hasty measures sure to excite heavy reprisals. He has petitioned Rome for help in reasoning with the seditious cell. Garnet's seriousness insofar as concerns spiritual matters stands, as does Anne Vaux's, in contrast to the folly of the Catesby-Fawkes contingent as well as the predations of the Sate by way of its legislators, executives, administrators, and "poursuivants," that latter terminology including what we might call secret police avant la lettre as well as your infiltrators and your informants. The State has intelligence organs, so to speak, and they shall prove crucial. Garnet, his own sisters nuns at Louvain, grapples legitimately with greater questions, beholden to higher sanctities, and the earthly sectarian fracas is parallel at best to the matters that actually…matter. Nourishment keeps body attached to soul, Garnet believes, and he experiences all of his struggles as a tugging in both direction, both toward the celestial and the earthly, the embodied. Our great novels about priests, whether authored by a Georges Bernanos or a J. F. Powers, have always been about the struggle to both retain faith and be adequate to that faith faced with the pressures of the earthly quotidian. A FIFTH OF NOVEMBER is in large part continuing that tradition. If Garnet has sexual urges and experiences doubt concerning his resolve, he is a man (very much a man) who might well on occasion attribute to dumb luck what we might expect a great Jesuit to imagine divine decree. It is in these moments that West seems most fully to capture the nobility of his tragic hero. Is is the chinks in the armour that are the true source of dignity and thus true strength, genuinely creatural fortitude. Contrary to both Papist and Protestant alike, Garnet's is generally an encompassing, inclusive orthodoxy: "Infinitely curious about human kind, Father Garnet decides that the main fatuity consists in the way humans fix on what divides them rather than on what they hold in common." If Garnet is fated to be executed by the State, this being a foregone conclusion, a matter of the historical record, the ultimate charge against him is not that he actually conspired with the plotters, no matter what underhanded smear tactics may be introduced, but rather that he refused to betray them to the State, his conundrum in this regard similar to that of Montgomery Clift's Father Michael Logan in Hitchcock's I CONFESS, a belief in the sanctity of the confessional ultimately handed over to juridicial scrutiny and/or broadly legalistic personal anxieties. For a time, Garnet lives in hiding, like the gunpowder conspirators and so many English Catholics directly before him, in "priestholes," "hiding month after month in abysmal quarters unfit for animals." Eventually he is captured, remanded into custody, made to face trial and invidious damnation. His main persecutors are Edward Coke and the Machiavellian Robert Cecil, "these militant Saxons," Cecil something like Garnet's dark double, provocateur and angler, sinister confessor. "Cecil, the trimmer, adjusts his sights, supporting James of Scotland for two years of sedulous cultivation, secret of course'just the sort of ministration Father Garnet wants to bring to bear on the hothead plotters: gradual, temperate suasion, with Garnet the most agile cajoler ever seen." Garnet is answerable for nothing more than "guilt by association," and his captors doubtlessly know it, though this will not and cannot stop them from drumming up more salacious charges. Garnet is interrogated endlessly, tortured on the rack. He turns in captivity toward the prodigious intake of palliative sack, human all too human. There is a show trial. "Father Garnet knows it is useless arguing…" Coke calls Garnet the serpent and Anne Vaux Eve. It is all horseshit bluster, nakedly so. A Yorkshire (or maybe Norse, "right from the Vikings") expression: "we'll eat a peck of muck before we die." Whatever his doubts concerning his capacity for forbearance, Garnet's nobility will withstand the destruction of his flesh, a fact not lost on the onlookers, the tableau bone-chilling. "Father Garnet is going to die, he now knows, having denied what an eternity-bound man does not need, and no amount of chivvying and pestering on the scaffold by Protestant prelates is going to sway him. He is all direction, and speed, not theirs, not his, not hers, but a mote hieing." Shortly before the insidious wheels of so-called justice produce the foregone conclusion, we will be asked to consider how "We Catholics are always attentive to the dying we do, from day to day, then at the end." But something of Father Garnet remains after his mortal life is stamped out, and THE FIFTH OF NOVEMBER goes to great length in its final pages to enshrine this with dexterous profundity, Anne Vaux, who has escaped execution, custodian of this jewel of a legacy we have access to the weighty consideration of here in the ignoble 21st century, both by way of West's novel and beyond it. Think of the Guy Fawkes mask, immortalized I guess anew in Alan Moore's graphic novel V FOR VENDETTA, the dubious Hollywood movie adapted from it, and the subsequent ubiquitous appropriation of that mask by the decentralized hacktivist organization (or quasi-organization) Anonymous. (Alan Moore also wrote FROM HELL, a graphic novel concerning, uh, the Women of Whitechapel and Jack the Ripper.) In Moore's graphic novel there are a pair of panels in which a spectre in the mask declaims that "THERE'S NO FLESH OR BLOOD WITHIN THIS CLOAK TO KILL. IDEAS ARE BULLET-PROOF." Perhaps the "eternity-bound" Garnet, pulled between the earthly-embodied and the celestial, can be read less as a pious man mindful of salvation in the eternal hereafter than as a creature of the earth in communion with ideas, a veritable receptacle of ideas and connoisseur of same, these being ideas he has helped to spread, to imbue with new depths of ineradicable import, immortal ideas, or at least bullet-proof, that will live long after his individual candle has been cruelly snuffed. THE FIFTH OF NOVEMBER is constructed in such a way that futurity is explicitly on the table. There is a passage, for example, in which Vauxhall is noted to be the future site of a "famous car factory," and a later, lengthier one, pages 128 and 129, in which Cecil is compared to Joseph Goebbels. We might also consider that the novel, West's penultimate, was originally published just short of four months before the attacks of September 11, 2001, subject, more or less, of his ultimate. The reprisals and invective that have targeted Muslims in the 21st century, a terrorist attack evidently conducted by a fanatical cell having played with pronounced instability into the themselves unstable hands of hegemony, bear a certain stink, and analogous one, as it were, to the miasmic odeur blanketing the first decade of 17th century England. Eternal return of the same mixed with a little difference and repetition. I think of Little John, his real Christian name Nicholas, workman, helpmeet to Garnet and Lady Anne: "life is too short, so is he." It's a good line. It is playful, a little flippant, product of West's superhuman literary grace, fun grace, ebullient, emblematic as such. In some sense it might also be erroneous. Very little John is very huge indeed, and life is so much bigger than our circumscribed socially mediated environs. You are never for a moment anywhere that history is not available to be pried impossibly open, the whole of it too massive to assimilate as anything like manageable datum, the eternal the constituent firmament, it's non-container. And Little John there, a minor character in a Paul West, standing in for all sublimity of impossible scale, a jewel I am inspecting in my hand. Impossible hugeness in the palm of my hand. Canada. February 2020. |

Review # 2 was written on 2010-06-22 00:00:00 Daniel Gleason Daniel GleasonI have read only one other book by Paul West, and both Terrestrials and A Fifth of November show him to be a writer intoxicated as much by his subject as by the words he uses. Expecting more of the post-modern guessing games about who is actually writing the novel, which figured prominently in Terrestrials, I was pleasantly surprised to see I was dealing with a straight forward narrative about the Gunpowder Plot and Father Henry Garnet, superior of the English Jesuits, who is by association implicated in the events. The novel makes clear the schism that ran through English life at the time, that despite more than a century of Protestantism, the country was still riven by religion, and persecution. A novel like this makes clear that the events behind England's fun-filled annual celebration of effigies, bonfires, and fireworks on November 5th have been blithely forgotten, and that the supposed conspiracy was half baked and worked into a fever pitch crisis of state by political figures intent on maintaining unquestioned power, exerted with force and torture, with bodies mangled and maimed and displayed with bloody glee. Father Henry Garnet's personal predicament is made all the worse because he is innocent, which is of little concern when it comes time to expunge from the country the Jesuitical influences that "conspire" against James I. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!