|

|

The average rating for A Delusion of Satan: The Full Story of the Salem Witch Trials based on 2 reviews is 2.5 stars.

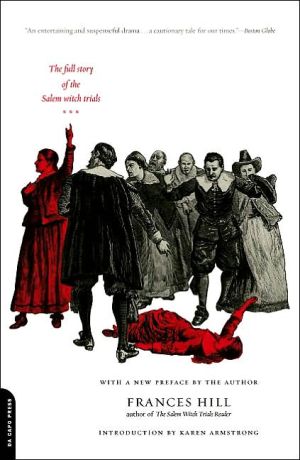

Review # 1 was written on 2013-08-16 00:00:00 Dave Stephens Dave StephensUndoubtedly, the Massachusetts of the 17th century would have been a terrifying place for a Puritan colonist. Beyond the gridded towns and the tended fields, a giant wilderness would have loomed, huge dark forests that hid ferocious bears, stalking panthers, larcenous squirrels, and possibly homicidal raccoons. The forests also would have hid Indians, the most terrifying creatures of all. Possessed of an almost mystical connection to the land, the Indians could appear, strike, and vanish at any moment. They killed settlers in their beds, dragged women and children into the woods, and were reputed to be cannibals. If these worries were not enough, Puritan leadership filled their followers heads with hogwash about demons and devils and evil spirits. It made for an environment in which clear thinking and logic paled before cries of "She's a witch!" In 1691, in Salem Village, religious repression and fear combined with baser ingredients of boredom and greed boiled over into the infamous Salem Witch Trials. The furor began with young girls - Betty Parris, Abigail Williams, Ann Putnam - acting strangely after having their fortunes told. Their fits proceeded (naturally!) into the baking of a "witch cake," the secret sauce of the cake being the girls' urine. Pretty soon, more girls were having fits. Then they started accusing townspeople of bewitching them. When it finally ended in 1693, 19 people have been hanged and one person (Giles "More Weight" Cory) had been pressed to death. In the annals of religion-fueled violence, the Salem Witch Trials were relatively small time. Compared to the Inquisition, it barely registers. Yet 322 years later, they are still at the forefront of our consciences. Partially that is due to its perceived historical irony - intolerance, zealotry, and bloodletting in the land of tolerance and religious freedom. Partially this is due to the event's metaphorical malleability, and how different generations can retool the story to suit its own needs (see, e.g., Arthur Miller's The Crucible). I've read The Crucible (and seen the fine film adaptation starring Daniel Day Lewis) but until Frances Hill's A Delusion of Satan I'd never picked up a book devoted solely to the subject. Frankly, finding a suitable title was a bit difficult. A lot of the titles seemed vaguely disreputable or were written or published by unknown authors/publishing houses. I really didn't know where to start. As you might have guessed, I started here. At just over 200 pages, A Delusion of Satan is a crisp, briskly-paced version of the Witch Trials that is unsparing in its portrait of a dour, repressive, superstitious community. The Puritans embraced the Calvinist doctrine of predestination, meaning that God saved people based on His whim, not necessarily according to what people did on earth. Of course, to Puritans, it seemed possible to tell - based on outward appearances - who would be saved and who would fry for eternity. Their theology, however, made it impossible to know with any certainty. This created, as Hill notes, the "characteristically New England Puritan mix of smugness and fear." Even though God had already made his decision, the Puritans were very particular about the rules. Rule Number 1: No fun. There were no other rules. Among the offenses punishable in Salem Village were having sex, sleeping during church, and "railing and scolding." The consequences of such acts included pillory or stocks, public whippings, and execution. (If you read Cotton Mather, you will find him describing a man put to death for having sex with livestock). According to Hill, this rigid, inflexible atmosphere led the young girls of Salem into rebellion. It started with a lark, dabbling in fortunetelling to ward off boredom. It took on a life of its own. Interestingly, Hill does not believe the children were faking their hysterical fits. [F]ew would doubt that repressed feelings may give rise to physical symptoms. When an individual's emotions, desires, and will are subjugated almost completely to the demands of society, those symptoms can assume the severity of paralysis and fits. This subjugation to society was even more profound for women and girls, both denied "self-expression and power" to a far greater degree than men (at least the free white men). Like much in this book, Hill's belief is speculation. But it's speculation that is warranted, explained, and based on logical inferences from the evidence. Indeed, Hill's analyses and suppositions are among the best parts of the book. Despite occurring so long ago, there is a lot of primary documentation about the Witch Trials. Cotton and Increase Mather wrote books. The Puritans - being litigious-minded - kept trial records. These primary sources, however, are of a very particular type that does not give us great psychological insights. Hill provides that, and in doing so, makes the story much richer and humane. A Delusion of Satan does not set out to be a complete, day-by-day look at the Witch Trials. Hill tends to follow certain narrative strands and personalities while eliding others. There are times when I had to refer to the chronology at the back of the book to see where things were on the timeline. I was fine with that. Trading absolute thoroughness and minutiae for evocative focus makes for a more entertaining book. And this is an entertaining, lively book. By the time you've finished - and seen the Puritan witch-hunters looking for "preternatural teats" on the bodies of women - you will have hearty dislike for a distinct group of people that passed from the stage three centuries ago. If you've only consumed the Salem Witch Trials through Arthur Miller's prism, you take from the Trials a lesson in the dangers of paranoia and groundless fear and mass panic. But hunting "real" witches in Salem and metaphorical witches (Communists) in the United States are two entirely different events. The actual historical event of the Witch Trials has a somewhat different lesson from the Red Scare. (Of course, as Miller obviously realized, there is a lot of overlap, especially in the way the "hunters" managed to benefit from finding their "witches." Both Joseph McCarthy and Samuel Parris gained power by tilting at these windmills). The real story of Salem is how religion can be used to coerce, to control, and to advantage those at the top of the hierarchy. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the powerful men of Massachusetts were able to brush aside accusations of witchcraft against them. The accusers were treated with absolute respect, up until the time they started pointing fingers at the powerbrokers. At that point, they became silly girls. Those accused of being witches lost everything. Their lands and homes and livestock were seized and sold. Not coincidentally, those lands and homes and livestock went to those people who supported the witch hunts. The Mather brood - father Increase, son Cotton - did their best to facilitate the belief in witches, because in doing so, they forced people to be dependent on God. Dependence on God manifested itself in a dependence on the physical church - that is, a dependence and obeisance to the church leaders. Men like the Mathers. A Delusion of Satan works so well because it understands what underlies the Witch Trials - greed, coercion, repression, false fear - and what finally ended them: logic, rationality, skepticism, and questioning of authority. |

Review # 2 was written on 2013-06-06 00:00:00 Ryan Hawes Ryan HawesAs an academically-minded graduate student in Literature and Theology, I could not get through this book. While it does fulfill the promise of providing a broad overview of the events that did occur, each narrative is flooded with Hill's personal beliefs, beliefs that consistently ignore the contextual and contemporary perspectives. Many phrases like "one can easily imagine" attempt to make the reader believe that Hill's explanation, usually one about a fradulent, fear-mongering Puritan society that doesn't actually believe its beliefs, seem like the only possible one. Sentences like "Never was the principle of the leading question eliciting the expected information more graphically illustrated" and repeating use of "leading questions" in the midst of what is supposed to be an account of the most accurately recorded (according to Hill's commentary) interrogation are hardly academic and barely allow a reader that did not have an opinion before beginning a book to come to any thought other than Hill's. Hill begins judging Puritan society and belief in the first pages. Karen Armstrong's Introduction sums up accurately Hill's apparent starting belief, that "They [Puritans] also brought from Europe an inadequate concept of religion" (ix). I was able to read through the end of the fourth chapter, but when the fifth chapter began "Charles Upham, writing in the mid-ninteenth century, believed that Parris and Thomas Putnam had told Tituba in advance what to say when she confessed" - such a preposterous idea that does not fit at all what we know about Puritan society and yet is presented here as the best of all research conducted - I knew, then, that I was doomed, and would not find in this book the good historical overview that pays attention to actual, contextual historical realities. This is the book for you, only if you are looking for an easy, simple excuse to be made for the terribly tragic and incredibly influential events of late 17th-century Salem. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!