|

|

The average rating for Woodsong based on 2 reviews is 4 stars.

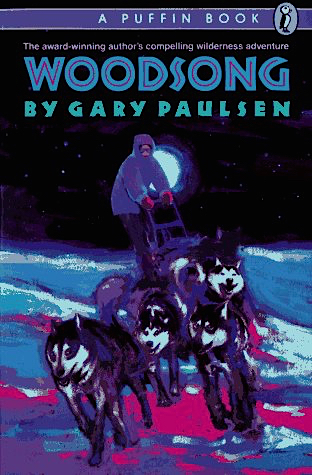

Review # 1 was written on 2015-12-29 00:00:00 Jonus Russell Jonus RussellAt the height of his acclaim in the mid-1980s and into the '90s, three-time Newbery Honoree Gary Paulsen was compared to some of the finest names in the history of American children's literature. Not only that, but the comparisons were to a diverse array of accomplished writers, indicating a versatility perhaps unequalled among his contemporaries. There was likeness drawn to the legendary Jack London, whose prolific output and sensitivity to the natural world's underlying wisdom was on a similar level as Gary Paulsen's. The Master himself, Robert Cormier, was occasionally brought into the Gary Paulsen conversation. Perhaps never has there been an author for teens who outperformed his peers as convincingly as Robert Cormier, but if anyone active after Cormier's death in the year 2000 had a small piece of his genius within them, it was Gary Paulsen, as evidenced by books such as The Rifle and Paintings from the Cave: Three Novellas. Even Paula Fox's name was invoked in discussions of Gary Paulsen's excellence, a Newbery Medal winner whose crossover success between children's lit, young-adult novels, and adult fiction was unsurpassed by all who sought to gain audience with the three distinct demographics. Gary Paulsen's talent placed him in the company of three of the very best to ever ply the trade, each comparison made with a different aspect in mind of his award-winning genius. Woodsong is as offbeat a novel as any penned by Gary Paulsen, intended for kids and teens yet featuring a protagonist in his late thirties and older. It's the depth of philosophical discovery that makes this book better suited to young readers, a quality of thought that demands an audience not fully formed in their view of the world, open to being shaped by the experiential knowledge Gary Paulsen gained from the ways of nature. When we come upon Paulsen at the start of Woodsong he's already an apt outdoorsman, capable of taking care of himself, his family, and his many domesticated animals in the distressing cold of where they live in northern Minnesota. After the government issues a bounty on beavers to help control their destructive population, Paulsen establishes a trapline route across a fifty mile radius near his home, and begins raising dogs to pull his sled through the snowy land so he can regularly check his beaver traps. Purchasing the dogs ushers in a new era for Paulsen, whose moderate success as a published author hasn't earned him great wealth, leaving him dependent on the money from beaver pelts to support his family. The sled dogs will teach Paulsen life truths that haven't made their mark on him yet, existential realities he probably never could have accepted apart from time spent with unfettered wildlife, animals interacting with their environment and mankind organically, apart from the illusion of inherent human superiority that modern technology projects. Paulsen's dogs will be his spiritual counselors, nourishing his soul as he feeds their bodies and tends to their physical welfare, and this experience is the breakthrough he needed to write stories that captivate the imagination of the public, taking a struggling smalltime writer from the north and vaulting him into a position on par with the all-time greats. Whether working the beaver trapline or later as they trained for and competed in the 1,100+ mile Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, Paulsen's success became inseparable from that of his dogs, and his greatest literary triumphs could be traced to the meeting of minds between man and majestic canine warrior. The front cover and plot synopsis of Woodsong indicate it's the story of Paulsen's first Iditarod, but it's more about his early dog-sledding years, raising his team from pups and growing in his own understanding of why they run and the role he plays on the team. The man riding the back of the sled has a crucial job, but he's hardly leader of the pack; that's the head dog's job, studiously evaluating the landscape and electing where to go based equally on instinct and intelligence, not the commands of a human musher with a dubious sense of direction. Paulsen had to be trained when to assert his will and when to back off and let his dogs sort out the situation, and his proficiency as a musher gained more solid footing as his discretion improved. Moving a team of hulking sled dogs hundreds of miles a night in temperatures dipping as low as minus forty, fifty, or sixty degrees is dangerous, but if his dogs were up to the task than he could do it, too. Their example instilled within Paulsen the indomitable spirit of canine nature, a rare gift impossible to develop apart from kinship with the animals in the intimacy of their pack. Nature isn't a finesse teacher; one learns its lessons quickly or dies, as Brian Robeson finds out in Gary Paulsen's Brian's Saga series. Paulsen is the sink-or-swim student in Woodsong, observing the strange, fearsome beauty of nature and adapting to his own minor role in its vast circle of life. An early run with his dogs leaves an indelible impression on Paulsen for its confrontation with uncensored wildlife death, the inglorious climax of a wolf hunt as the predators track a terrified doe onto an icy lake and tear the animal to shreds while it's still alive to experience its own disemboweling. Paulsen stops his dog team to stare at the savagery of the massacre, gorily described in the rawness of bloody battle, the rending of flesh and entrails and vital organs with carnivorous teeth. This isn't the fascinating game of hunter and hunted shown on television, crude violence carefully edited out of the footage. This is real wilderness eat-or-be-eaten, and Paulsen is sickened by it. But thinking back on what he witnessed and how he reacted, Paulsen sees that his revulsion for the wolves is the only element that didn't belong in the equation, him carrying his prejudices of modern human civilization into the natural world and expecting animals to follow the rules he unconsciously set for them. Wolves are wolves, predators knowing only the drive to kill and eat, kill and eat however possible, with no concern for their prey or if their technique in bringing the creature down looks pretty. It was unfair of Paulsen to demand the wolves conform to his expectations, an uninvolved species peering in on the ancient art of the hunt and judging it. "I began to understand that they are not wrong or right�they just are. Wolves don't know they are wolves. That's a name we have put on them, something we have done. I do not know how wolves think of themselves, nor does anybody, but I did know and still know that it was wrong to think they should be the way I wanted them to be." What does this mean for all of life, extending beyond the animal kingdom? Its implications for the view humans take of one another is sobering, asking us to reconsider what we think of individuals who deviate from the code of conduct written by mainstream society, demanding they adhere to those values or be branded monsters who deserve to be put down for their crimes against decency. But does the predatory human differ from the wolf chasing down deer and ripping them to bloody bits in the wild, caring only to satiate the natural craving within their own breasts? Is it fair to deem such a person worthless or wicked and condemn them to incarceration or death if all they're doing is being themselves, wolves who don't know they're wolves and couldn't do anything to change it even if they were aware? Gary Paulsen's anecdote is loaded with implications that deserve honest examination. It could occupy the thoughtful reader's mind for a long time on a number of levels, and if you're reading Woodsong for the first time, get used to it: this quality of food for thought fills the book from start to finish. "Fear comes in many forms but perhaps the worst scare is the one that isn't anticipated; the one that isn't really known about until it's there. A sudden fear. The unexpected." �Woodsong, P. 36 Once Paulsen gets the hang of driving his sled dogs, the feeling is incredible, and thrillingly captured by the evocative sensuality of Gary Paulsen's tight, immediate prose. He wrote Woodsong at the peak of his career, and it clearly shows. Paulsen speaks of his lead dog Storm with fierce admiration and affection, delving deeply into the story of a night when Paulsen's early lack of experience with sled dogs led to a blunder that threatened Storm's life. Miles from home and bleeding rectally at an alarming rate, Storm ignores his own internal wound and refuses to be pampered while the rest of the dogs run, frantically resisting Paulsen's attempts to take him onto the sled and tend to his bleeding. Paulsen helplessly watches the life ebb from Storm with every fresh burst of blood onto the pearly snow, knowing he has to get this animal home immediately or Storm will perish because of Paulsen's inability to properly care for him. The blood horrifies Paulsen, but to Storm it's nothing, certainly no reason to abandon his sled team to do all the work while he rests. Having no other choice, Paulsen reties Storm to the sled and starts for home, resigned to this being the dog's farewell run. In hindsight, however, Paulsen sees the lesson Storm imparted to him that night, one he had to learn if Paulsen were to become an effective driver of the sled. "To Storm, it was all as nothing. The blood, the anxiety I felt, the horror of it meant as little to Storm as the blood from the deer on the snow had meant to the wolves. It was part of his life and if he could obey the one drive, the drive to be in the team and pull, then nothing else mattered." Storm's lesson is as applicable to human society as the lesson of the wolves, a clearheaded observation of anxiety and how we allow it to cripple us because of our heightened human intellect. We fear blood; we fear hurt, worry, sadness, and grief so much, keeping it as far away as possible, dashing to the other side of the street to avoid it, fleeing when we think we see its approach, that we sometimes forget to live life without regret. We lock ourselves indoors at the mere hint of fear's shadow, and thus miss seeing the possible beauty of what happens next, whether or not our anxiety comes to pass. It's vital to not always run from the threat of blood, to acknowledge our fear of taking damage physically, psychologically, emotionally, socially, or on any front, and accept that living a full life means surviving terrible trauma now and then, trauma we see coming miles in advance and sudden scares that leave us badly shaken. No one wants to be hurt, but if you're alive it's going to happen, and repeatedly. If we acknowledge that to ourselves and resolve to keep running despite the blood, following the course we were meant to travel and bravely allowing whatever will be to be, we open ourselves to live unencumbered by fear, to feel satisfied that we ran our hardest and lived life to the max no matter how it turns out in the end. We can't let fear deter us from participating in the race. Paulsen never could have learned this truth in such unforgettable fashion apart from Storm, who had yet one more major lesson to teach him before his life was through. Paulsen was saved by his dog team more than once on those bitter cold nights in woodsy Minnesota, flying over snow moguls and rocky shelves, through towering forest greenery and down mountain ledges that imperiled the lives of man and dog if they didn't proceed with due caution. As a newbie musher, Paulsen occasionally didn't take the wilderness seriously enough, and it was left to his dogs to bail him out. After one such occurrence when the tenacity and allegiance of a sled dog named Obeah was the only reason Paulsen lived, he began seeing the advantages dogs have over humans, especially their closeness as a pack that people have largely eschewed in favor of independence. "I knew that somewhere in the dogs, in their humor and the way they thought, they had great, old knowledge; they had something we had lost. And the dogs could teach me." It's the openhearted quest for this wisdom that deepens Paulsen's character and insight as a writer, pushing him to discover hidden truths within himself. It's what compels him to eventually sign on for the Iditarod: not a driving desire to best the competition and finish in the money, but to better know himself and his team of canine companions, to live without limit and feel what it means to be a momentary part of teeming humanity on this earth, with no modern distractions to keep him from his goal. The Iditarod is the place to do all that, but running the race will be much harder than even Paulsen realizes. Woodsong is really a collection of related short stories leading to a somewhat longer concluding narrative about Paulsen's Iditarod experience, but I want to talk about two more of the earlier short stories before wrapping up my review. Paulsen indicates in the opening chapters of the book that he's personally opposed to animal trapping even though that's how he got his start running sled dogs, but it's his explanation of an incident between his dogs that finally tells why he stopped trapping. Columbia was a favorite sled dog of Paulsen's, an animal of tremendous personality, and one day as Paulsen observed Columbia with a less sophisticated dog named Olaf, cleverly teasing Olaf with a morsel of food, Paulsen realized that Columbia had a sense of humor. If a dog is capable of playing pranks, of showing that complexity of personality, then other animals must be, as well. For Paulsen, that was the last straw when it came to trapping. Personality is part of what makes us human, gives us pause before causing serious harm to a consciousness like our own, and the idea that animals could demonstrate human personality traits robbed Paulsen of any desire to kill and skin them for profit. Who can slaughter a creature who laughs and understands and has a sense of irony? But the lingering lesson Paulsen is taught by his dogs in Woodsong, far and away the most powerful lesson of the book, the part that brings me to give Woodsong three and a half stars and round it up to four, is the story of Storm's twilight years, the fading of a wondrous animal after his retirement and the final, emotionally charged scene he shares with his owner. This simple anecdote blows the doors off Woodsong, spirits us away to an isolated patch of rural Minnesota where the bond between man and man's best friend can still be as poignant as any, where an indefatigable sled dog warrior can lay down his head and know it is finished, that he ran the races he was meant to and entered that eternal light with the best commendation possible: as a Good Dog, the hero of the man who raised him. The direction he walked into that light didn't make so big a difference, Storm understood at last. And he'd find a way to assure Paulsen of that, too. There's a blurb from Kirkus Reviews on the back of my copy of Woodsong that puts it succinctly: "Paulsen's best book yet." With The Rifle yet several years from release, that may well have been true; I say Woodsong is superior even to Hatchet and The Winter Room. Many exceptionally substantive teen novels require four or five hundred pages to get their message across, but Gary Paulsen has fine-tuned the art of conveying his point in not much more than a hundred pages, and usually does it better than books quintuple that length. Woodsong is a marvelous junior novel that leaves me puzzled why only two Newberys were handed out in 1991�the Medal to Jerry Spinelli's Maniac Magee and a single Honor to Avi's The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle�when a book as deserving as Woodsong was eligible for the awards. I wouldn't rank it ahead of either winner, but surely it earned a Newbery Honor spot of its own. Regardless of awards, Woodsong should maintain its power to sway hearts in any time, place, or culture, a novel packed with hard questions and transcendent storytelling, an immutable anthem of what makes us alive and what defines us as human. What a book. What an author. What a life. |

Review # 2 was written on 2015-07-05 00:00:00 Drake Maliko Drake MalikoListened to it on audiobook read by the author and it was great. Absolutely loved it. Paulsen was one of my favorite authors as a child and I am glad to see that my trust in him as an author was well-deserved. The descriptions of the cold were so chilling and unsettling that I had to turn this off a couple of times, but the honest tone about the brutal world of dogsledding made it all worthwhile. I also deeply appreciated the mantra that Paulsen hammers home in this story -- the "I didn't know how little I actually knew about this subject, and I was an idiot. I know more now but I'm still an idiot." Something about that basic humility in the face of nature is so refreshing and so true. I definitely did not want to hear about some white guy trying to get back in touch with the wilderness and pretending he was Iron Will along the way; no no, this was just the right balance of self-deprecation and respect for wilderness. |

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR? CLICK HERE!!!